The abyss of demographic winter

A journey through the major demographic risks in human history, from the threat of overpopulation to the abyss of demographic winter.

Beyond personal fears lie fears that transcend the individual. Fears about the future of humanity, how far we will go and what might be the last stumbling block we encounter, the one that marks the point of no return.

This is precisely the subject of a book I read a few years ago, The Precipice, by Australian philosopher Toby Ord. Before delving into some of the risks facing humanity and possible solutions or measures to mitigate those risks, Ord establishes an initial concept that I find very interesting: the idea of existential risk and catastrophe. Within this, he not only takes extinction as the ultimate consequence, but also raises other possible consequences that could represent a point of no return for civilisation.

The compilation of risks and possibilities covered in the book is quite exhaustive. It includes natural risks (asteroids, supervolcanoes, and stellar explosions) and anthropogenic risks (nuclear war, climate change, environmental damage, and pandemics), as well as risks that we are not even aware of yet1. He devotes many pages to the risk of general artificial intelligence, which I will avoid discussing here.

What surprised me is that the book does not directly address demographic risks at any point. It talks about migration as a consequence of some risks, but it does not mention overpopulation, let alone the opposite, demographic winter2.

It is precisely the latter that will be the focus today.

The threat of overpopulation

The history of hominids, over hundreds of thousands of years, has been very similar to that of any other animal. Their population was subject to natural selection, with high birth and death rates. Selective pressure was usually linked to access to food and premature death, whether from attacks by other animals or from disease.

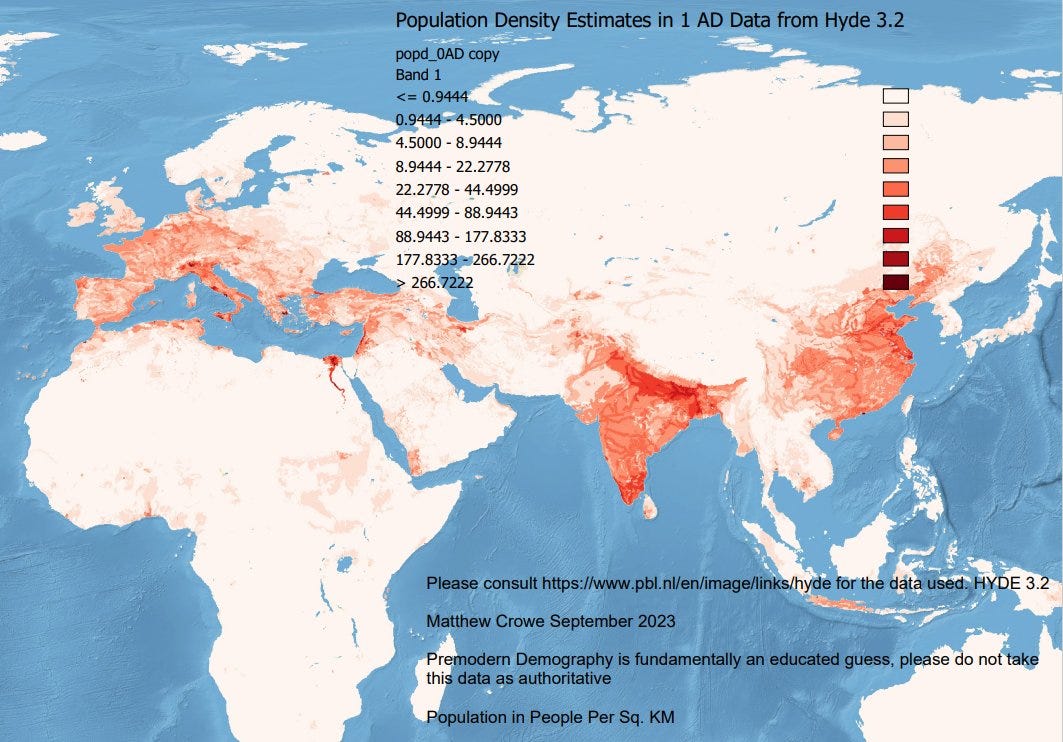

But at a certain point, among all the hominid species, Homo sapiens appeared, spread across the Earth, created the first settlements and learned to domesticate plants and animals. At the beginning of our era, the Earth probably had around 250 million inhabitants.

It took around 1,600 years for the human population to double and reach 500 million, partly due to the setback caused by the Black Death in the 14th century. From then on, things began to accelerate significantly. The year 1804 is often taken as the year in which the population doubled once again and reached 1 billion inhabitants for the first time. Industrialisation and medical innovation were marking a change of pace that seemed unstoppable.

In 1798, the English economist Thomas Malthus presented his essay on the principle of population. In it, he popularised the idea of the Malthusian trap (or Malthusian catastrophe), according to which he predicted that the population would continue to grow exponentially, doubling every 25 years, while resources would only grow arithmetically. This decoupling, according to Malthus' theory, would cause continuous impoverishment of citizens, leading to the extinction of humanity by 1880.

Extinction did not occur in 1880; however, the human population continued to expand at an unusually rapid pace. In 1927, the population reached 2 billion, and in 1975, it reached 4 billion. Gladly, technological advances continued to improve food production, and medicine made it possible to effectively combat diseases that were previously incurable. However, the fear of overpopulation remained latent in society, and many organisations continued to warn of the great threat and its consequences.

The demographic transition

After analysing demographic changes in several countries following industrialisation, scientists such as Warren Thompson and Adolphe Landry began to propose a series of demographic theories that would eventually be formalised in the 1940s by Frank W. Notestein. This model is known as the theory of demographic transition.

This model is based on a premise that can be verified with historical data: pre-industrial societies had very low growth rates, with very high birth and death rates. With industrialisation, societies moved from this paradigm to one of zero growth, in which both birth and death rates plummeted to record lows. The most interesting part of the model is how this transition occurs. The decline in mortality and birth rates occurs at different rates, allowing natural population growth (more births than deaths) to skyrocket during this period.

This model, which was initially created to explain industrialisation in the 19th and early 20th centuries, proved to be quite effective in modelling demographic changes throughout the 20th century. Industrialising societies experienced excessive growth, while those that had been industrialised for longer gradually stabilised their natural growth, bringing it closer to the equilibrium predicted by Notestein.

However, at the end of the 20th century, something began to happen that the model did not anticipate. There were countries whose natural growth did not remain at zero, but fell below the replacement rate.

This map shows in yellow the countries that fell below a natural growth rate of 0 before 2020. In different shades of blue are those that will do so in the coming years.

The demographic transition model has been useful, but the hypothetical end point is inconsistent with current observations.

The abyss of demographic winter

Although there are already many countries, mainly in Europe, with negative natural growth, where deaths outnumber births, there are still more countries where the opposite is true. Africa's great engine continues to drive growth, but fertility rates continue to decline worldwide, at a much faster pace than expected3.

This comparative map shows how most of Africa had a fertility rate above 6 children in 1970, while in 2014 only Somalia, Mali, and Niger still met this criterion. In the Maghreb region, the figure has fallen below 3 in all countries in just half a century.

The UN has been revising its global population growth forecasts downwards for several years. In 2017, the estimate was that the global population would peak in 2100, with a total of 11.2 billion inhabitants. A couple of years ago, in 2022, this was revised downwards, with an estimated peak of 10.4 billion in 2084. Global population growth is declining, and zero growth will not be the end point of this demographic trend.

We are already seeing how negative population growth in many countries is being offset by migration flows, but this solution may have significant long-term consequences. Few countries currently function as magnets for migrants, but this number will grow. China is already losing inhabitants, and fertility rates suggest that this decline will be very pronounced in the coming decades4. It will become increasingly common for countries in demographic decline to start competing for migrants from the few countries with positive natural growth.

This is what I call the demographic winter abyss, the idea that societies in the third millennium may not be able to achieve the replacement rate that will prevent us from falling into a spiral of demographic decline. There are many reasons why people are having fewer children: more contraceptive methods, more planning, more difficulty in balancing modern life with parenting, lack of resources, or simply the voluntary decision not to have children, which is my case.

I believe that the demographic winter is the most feasible conclusion for humanity. Of course, the future may hold many medical, technological or social changes that will entirely change the current paradigm, but with the information we have, I find it difficult to see a world that is not like this.

Maybe it will happen, possibly it won't. If it does, it will take many centuries, or even millennia. The only thing I can be sure of is that we won't be here to find out. Although, this does not take away a shred of existential anxiety.

To conclude, I would like to leave you with a few final (and important) points:

Although it is clear that human population growth is more or less capped, this does not mean that overpopulation is no longer a problem. As is often said, there are not enough material and energy resources to sustain 8.2 billion people living as they do in the most developed countries.

The concept of demographic winter was firstly coined by philosopher and theologian Michel Schooyans, and has been widely criticised for its original approach. In part, he blamed the incorporation of women into the labour market as a direct consequence of the decline in birth rates in Europe. I take up the concept here, but explore it further in a global context and without entering into such controversial and, in my opinion, simplistic understanding.

Along the same lines, the idea of ‘demographic winter’ is widely used in ultra-conservative contexts alongside other ideas such as ‘demographic suicide’ and ‘the great replacement’. Note that I have used the term ‘demographic winter’ because I find it poetic, but I find the context in which it is used in ultra-conservative circles despicable, especially when linked to ‘the great replacement’.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

For example, nuclear war was not something that any human being considered 100 years ago, but for decades it was humanity's greatest fear. And, well, also in films.

There is a big disclaimer about the use of this term at the end of the article. I am aware of its connotations and I disassociate myself from them completely. I am leaving the note here, in case anyone raises an eyebrow.

The fertility rate is the number of children per woman of reproductive age. This rate is considered to need to be above 2.1 to ensure population replacement.

Good post. I agree with you that it’s likely we will see the global population shrink, and maybe even sooner than 2080 like that Our World in Data chart suggests. But:

- I’m not sure we will see a spiral of demographic decline, if by that you mean that population declines will beget further population declines. If I anything I think the opposite is more likely — population decline will lead to, for example, cheaper housing, which will lead to a slower rate of population declines.

- While I don’t think it’s likelier than not, I would not be surprised if economic and technological changes lead to global fertility staying around replacement levels, or even a bit above replacement, in the not too distant future: a few decades or generations from now, rather than centuries or millennia. Some of us may live to see it, if that happens.

- If that does happen - if fertility stays at even just a smidge above replacement- then thanks to the always-surprising speed of compound growth, the world population could reach extremely high numbers (at least hypothetically) in the span of only centuries, not millennia. I wrote a speculative article about that here, if you are interested: https://josephshupac.substack.com/p/fertility-rates-in-utopia

…but most importantly, I’m glad you are only using the abyss of this winter poetically. As you say, people have been going nuts over this topic.