The Plague

Albert Camus dedicated a remarkable book to it. And with that as an excuse, this is a journey through the ravages of the plague throughout human history.

Five years ago, when what came upon us came upon us, I was tempted to read Albert Camus's The Plague for the first time. While we were in lockdown1 and were bombarded every few minutes with figures about how badly the coronavirus pandemic was going, sales of this book skyrocketed2. My strength, like most people's, was not at its highest, so I chose to leave it for later. A couple of years ago, I decided to finally read it, and I have to admit that I regret not having done it earlier3.

The plague ravaging the city of Oran is nothing more than an excuse for Camus to dive into the fragility of society and its individuals. There is no epic story, nor does it need one to explore fear, despair, hope, and solidarity. Camus’ plague is nothing more than an allegory of the times in which this work was published, 1947, after two world wars and a turbulent interwar period4. Even so, the way the Oranese and their concerns are described could well have been taken from any city in lockdown during 2020, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic. The political measures described in The Plague were replicated almost step by step in many countries and cities around the world more than seventy years after the book was published.

If you haven't read this book, I highly recommend it. It's not long or dense, so it can easily be read in a few afternoons. And it's well worth it.

Changing the subject, but staying on the same thread, I'll leave you with a handful of maps, while I talk about the plague, the real one. The one that ravaged half the world at various times in history.

The Antonine Plague (165–180)

If we stick to historical sources, there have been major pandemics since ancient times, at least since the first civilisations established complex networks of cities with movement of people and significant trade5. The Amarna letters contain what is possibly one of the first references to a pandemic as such, with a letter from the ruler of Megiddo to Amenhotep III discussing how a disease was decimating the Mediterranean Levant. In the 5th century BC, there are more records of diseases devastating Athens and Rome, but in both cases the absence of communication networks with large movements of people limited a wider impact.

With the Roman Empire, interconnection between territories increased significantly, thanks to its extensive road network, but also to improvements in trade and continuous military expansion. It was in this context, during the Antonine dynasty, that one of the best-documented pandemics of antiquity, the Antonine Plague, broke out. Despite its name, we now know that it was not caused by the bubonic plague, but possibly by smallpox or measles. In fact, some historians, such as William H. McNeill, argue that this was possibly the first time that Europeans were exposed to these diseases, which would explain the high mortality rate6.

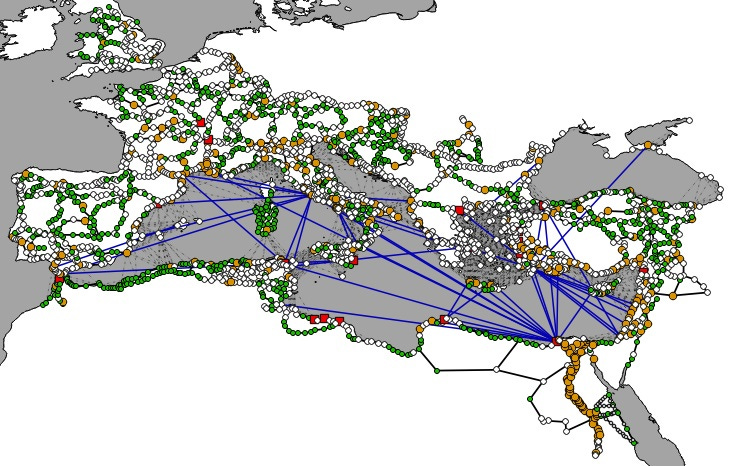

The first reference appears during the siege of Seleucia, in Mesopotamia, at the end of 165. From there, it spread rapidly throughout the Empire, reaching all its borders in a few years, from Egypt to Gaul. Despite being the best-documented pandemic of antiquity, sources are limited, making it necessary to establish models to better understand how it spread. This is where Michael Ditter comes in, a historian and cartographer who, 20 years ago, created the model you can see above7. To achieve this, he located on a map the 3,000 most important population centres of the Roman Empire at the end of the 2nd century, as well as the road network and the main sea routes.

Ditter's model helps to visualise a little better the great impact that the Antonine Plague had on the Roman Empire. The consensus is that 10% of the Empire's population died, which is between 5 and 10 million people. One in four people infected with the disease lost their lives, which means that almost half of the population was exposed. Ditter's map also shows that the impact was not the same in all regions. Egypt, Asia Minor and the Mediterranean Levant, precisely where there were large numbers of Roman legionaries, were the areas most affected.

The Plague of Justinian (541–544)

Justinian I, the Great, was crowned emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire in 527. Under the campaign Renovatio imperii Romanorum8, he set out to revive the extent and grandeur of the Roman Empire. This led him to occupy the coasts of the Adriatic Sea, the Italian peninsula, North Africa and even reach the south of the Iberian Peninsula.

However, the Renovatio imperii Romanorum was also important in multiplying the impact of the arrival of the bubonic plague in Europe. There is no consensus on the origin of the plague, but three hypotheses are generally considered: the Siberian steppes, the Indian peninsula or the Horn of Africa. What is clear is that trade in the Red Sea introduced it to Egypt between 540 and 541. From there, taking advantage of the Byzantine Empire's extensive network and with rats as its vector, the disease spread rapidly throughout the Mediterranean.

![r/MapPorn - Plague of Justinian, Eastern Roman Empire [1715x1065] r/MapPorn - Plague of Justinian, Eastern Roman Empire [1715x1065]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Ivnc!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffacbb0aa-6f03-488c-8a38-4f129ef8d44f_1715x1065.jpeg)

The result was devastating. It is estimated that between 25 and 50 million people died worldwide and that cities such as Constantinople lost almost half their population, with more than 5,000 deaths per day for several weeks in 542. The Balkan Peninsula was one of the worst affected areas, to such an extent that many areas were completely cleared out, facilitating Slavic migrations, who occupied the region for the first time during this period.

After this first wave, which lasted from 541 to 544, a second and third wave of the Justinian plague arrived. After 574, when the third wave ended, outbreaks were more localised, although they continued almost non-stop for two more centuries in Africa, Europe, and Asia. Then, from the middle of the 8th century, it lost prominence.

At least until the 14th century.

The Black Death (1346–1353)

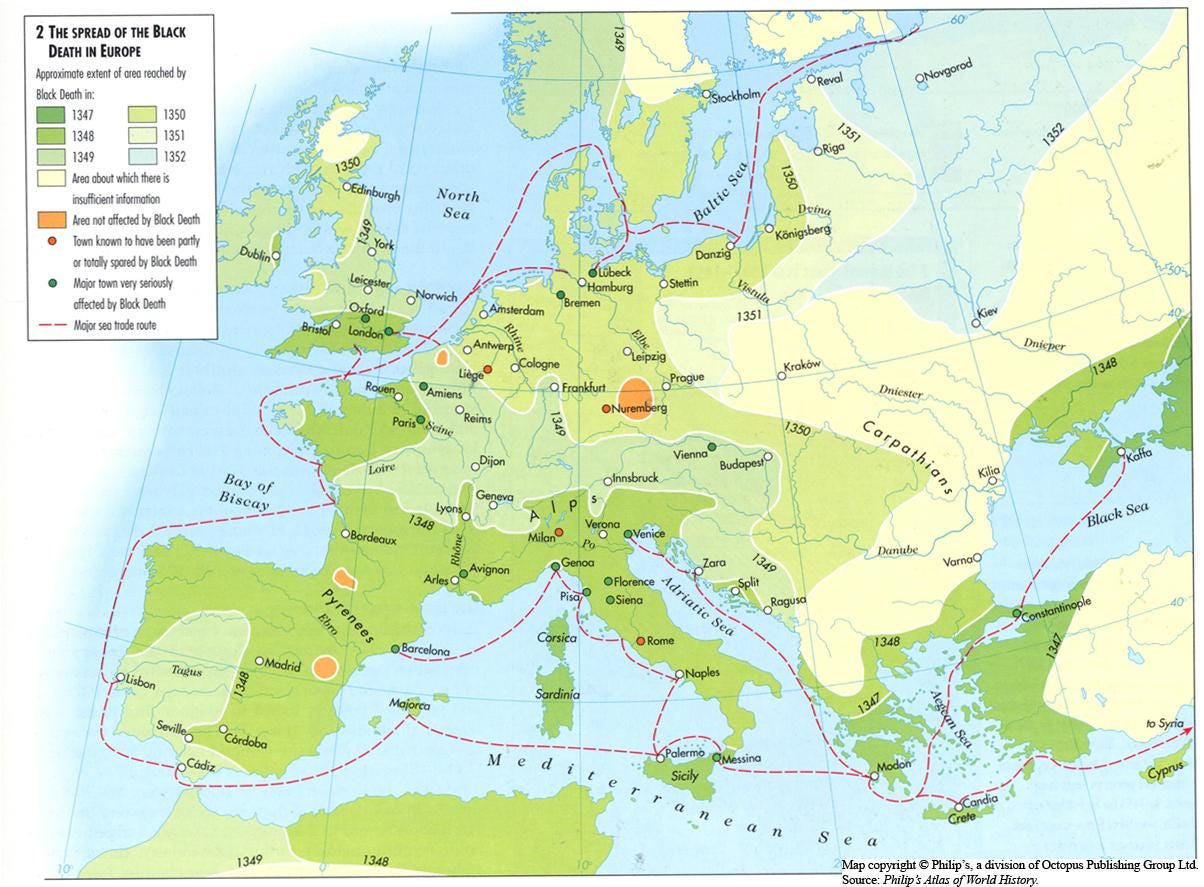

The most recognised of all pandemics in history can only be the Black Death. Most historians place its origin in Central Asia, near the current border between Kyrgyzstan and China. From there, this time with fleas as the vector, it spread rapidly to China and Europe. On this occasion, the contagion did not take advantage of an interconnected empire, but rather of the new trade networks that had been established between Asia and Europe, with major trade hubs such as Genoa and Venice. It was precisely in Crimea, under Genoese control, that the plague entered Europe in 1347.

The result was as devastating as the Plague of Justinian. It is estimated that around 50 million people died worldwide, although the focus was mainly in China and much of Europe. In 1348, when rulers were still trying to figure out what was happening, many cities were completely immersed in the pandemic. Tax records from Florence suggest that the city lost 80% of its population in just four months in 1348. A large proportion of the lost population died from the plague, although many others might have escaped and contributed to the spread of the disease throughout the rest of Europe.

Estimates in Northern Europe, where the pandemic arrived later, are not much better. It is estimated that large ports such as Bremen and Hamburg lost 60% of their population. The impact in Germany was so dramatic that the region went from having 170,000 inhabited settlements in 1340 to less than 40,000 in 1450. Even so, there is consensus that the Black Death was particularly deadly in cities and that many rural areas were hardly affected, as was the case in parts of the Balkans, Russia and Poland.

As with the Justinian plague, the Black Death was only the first event in a new wave of localised outbreaks that continued well into the 20th century. Today, although it seems like a disease of the past, there are still around 3,000 cases reported each year worldwide, mainly in the United States, South America, India, Madagascar, and China. Current prophylactic measures and knowledge of the vectors of infection have managed to keep bubonic plague confined to a few cases, and thanks to medicine, more than 80% of those infected can survive the disease with proper treatment.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

With varying degrees of freedom in each region of the world over a two-year period. In Spain, we were under full lockdown. We were just allowed to get out to buy some groceries until May 1st.

There are reports that sales skyrocketed between 20 and 50 times more than in 2019, with some countries such as Japan and South Korea leading the way, where it was the best-selling paperback for weeks.

Even more so when I consider that Albert Camus is one of my favourite writers and has been a fundamental pillar in my understanding of life.

There have been multiple epidemics in Oran throughout history, but Camus's work is not based on real events. The main influence on Camus's work was the cholera epidemic of 1849.

Speaking of networks, M. E. Rothwell has a wonderful series of articles on networks in his newsletter. I recommend specially the one on the Black Death, relevant for a deep dive from another perspective.

Without previous exposure, there is no immunity within the group, allowing the disease to spread freely.

Renewal of the empire of the Romans,

Reading through the history of these plagues makes you realise how lucky we were with Covid. The numbers involved in some of these pandemics are just so insane it's hard to get your head round.