Lost lands: worlds under water

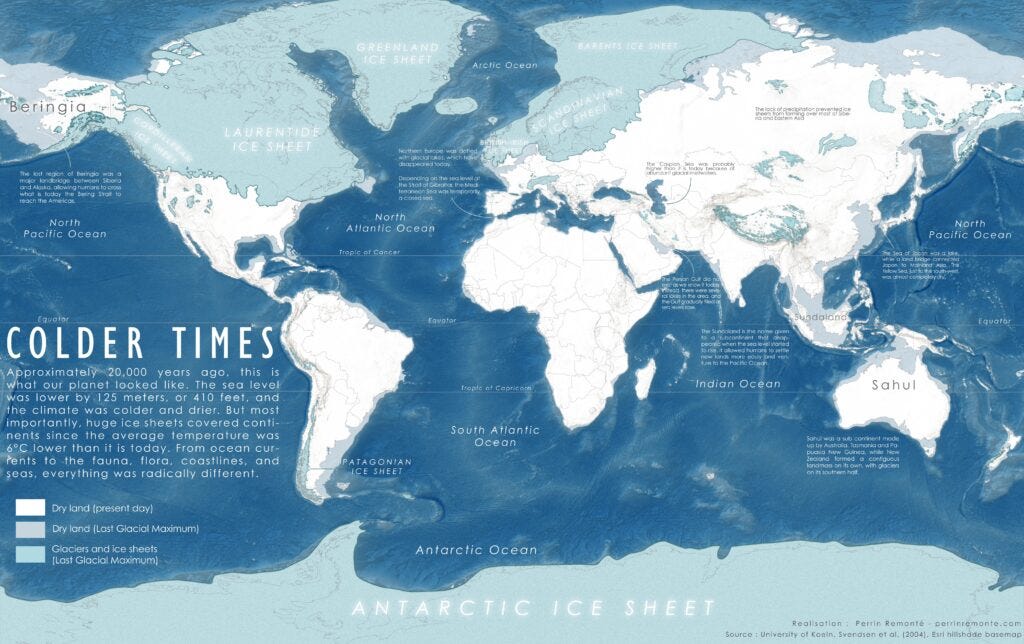

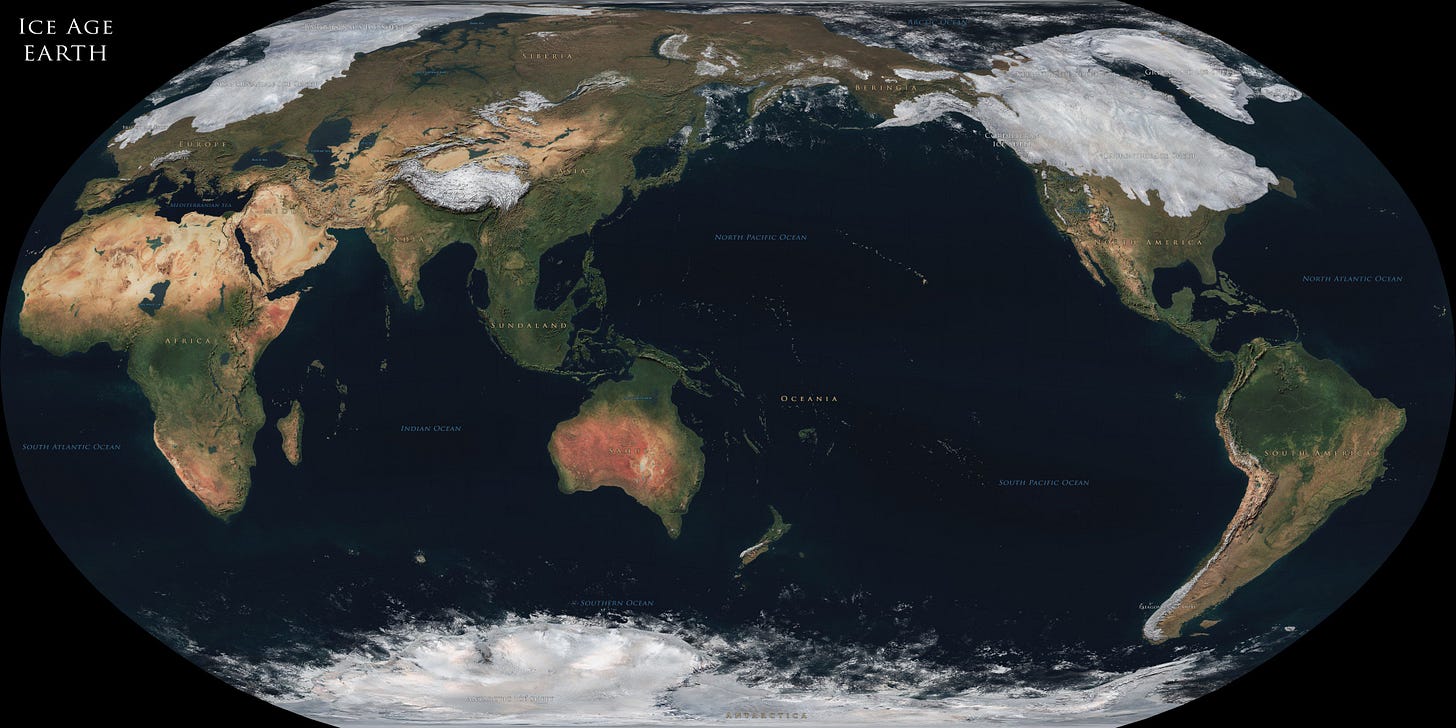

Doggerland, Sondalandia, Sahul, Beringia and many other lands that rose above sea level during the last Ice Age.

Last year, I wrote an article here about lost waters. It dealt with some of the largest prehistoric lakes we know of. Most of these lakes existed during the last glaciation, which peaked around 15,000 years ago. Back then, it was cold, very cold. In fact, the average temperature of the planet was about 5 or 6 °C below the current temperature1.

It all began about 110,000 years ago, in what is commonly known as the last Ice Age. In the field of geology, this glaciation has different names depending on the region we are referring to: Würm in the Alps, Weichselian in Northern Europe, Wisconsin in North America, Mérida in Venezuela, Otago in Peru, and Llanquihue in Chile. Practically, there is a name for each of the ice caps that appeared during this Ice Age, which lasted almost 100,000 years.

With so much ice stored around the world, it is not surprising that sea levels were between 100 and 120 metres below their current levels. As a result, much of the land submerged a few metres below the sea, considered part of the continental shelves, became dry land for a few thousand years.

Some of these lands, now lost, played a fundamental role in the history of humanity and even in the biodiversity of the planet. I will go through the most important, although I will also leave a handful of curiosities for the end, those that we rarely talk about.

Beringia

The Bering Strait, with a depth of no more than 50 metres at any point, currently separates America from Asia. But during the last glacial peak, there was a land bridge connecting the two continents: Beringia.

The temperature in Beringia was unusually warm. It is estimated that it could reach up to 10 °C during the summer, thanks to which it was able to remain ice-free, unlike Canada and the Arctic Ocean. This made the bridge walkable for at least two periods, the last one between 25,000 and 10,000 BC. And do you know what happened during that period? Humans crossed from Chukotka2 to Alaska, reaching America for the first time. They walked across the Beringia bridge.

The ecosystem was very similar to the current Siberian tundra, with many bushes and small vegetation. The map shows how there were lakes and rivers across the surface of Beringia, and also some isolated forests. The American fauna was completely blocked by the Laurentide Ice Sheet, so only animals from Asia, such as woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed tigers, lived here.

Doggerland

In Europe, the North Sea disappeared completely, and the British Isles were fully connected to the rest of continental Europe, with a territory known as Doggerland. In the central part of this territory lies the Dogger Bank, which is precisely what gives it its name, with a depth of only 35 metres. The rest of the territory is almost 100 metres deep, so it is possible that it was not above water for a long period of time.

Humans also populated these lands during the Ice Age, possibly alongside Neanderthals, as indicated by archaeological remains found at the bottom of the North Sea. This would be precisely when humans first arrived in Great Britain and Ireland.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing about these lost lands is the course of the rivers, which made the Thames and the Rhine part of the same river that flowed through the English Channel and into the Atlantic Ocean. And yes, during this period, the River Seine was also a tributary of this same great European river.

The most widely accepted hypothesis is that Doggerland gradually disappeared with the melting of the ice that ended the Ice Age. It is also thought that the entire region may have been affected by tsunamis caused by the Storegga Slides 6,100 years ago3. This put an end to the settlement of the region and separated British cultures from the rest of European cultures.

Sunda and Sahul

Southeast Asia, which is currently a collection of archipelagos with thousands of islands, such as Indonesia and the Philippines, was practically reduced to two large land masses. On the one hand, the Indochina peninsula joined the islands of Borneo, Sumatra and Java, forming what is known as Sunda. On the other hand, Australia merged with New Guinea and Tasmania, constituting what is known as Sahul.

In addition to being visually striking, this is particularly interesting when we consider that Wallace’s line lies between the two lands. This line marks a biogeographical division that separates, in a rather scientific way, the continents of Asia and Oceania. Looking from one side to the other, even though the regions are very close, both the fauna and flora are entirely different. In a way, this shows how, during the Ice Age, this line prevented the exchange of species.

As in the case of Beringia and Doggerland, these territories made it easier for humans to spread during the last Ice Age. At some point between 60,000 and 15,000 BC, humans managed to cross the Wallace Line and begin to populate Sahul.

More lost lands

The four examples of land masses we have seen are usually the most popular when talking about the last glacial peak, but there are many more examples.

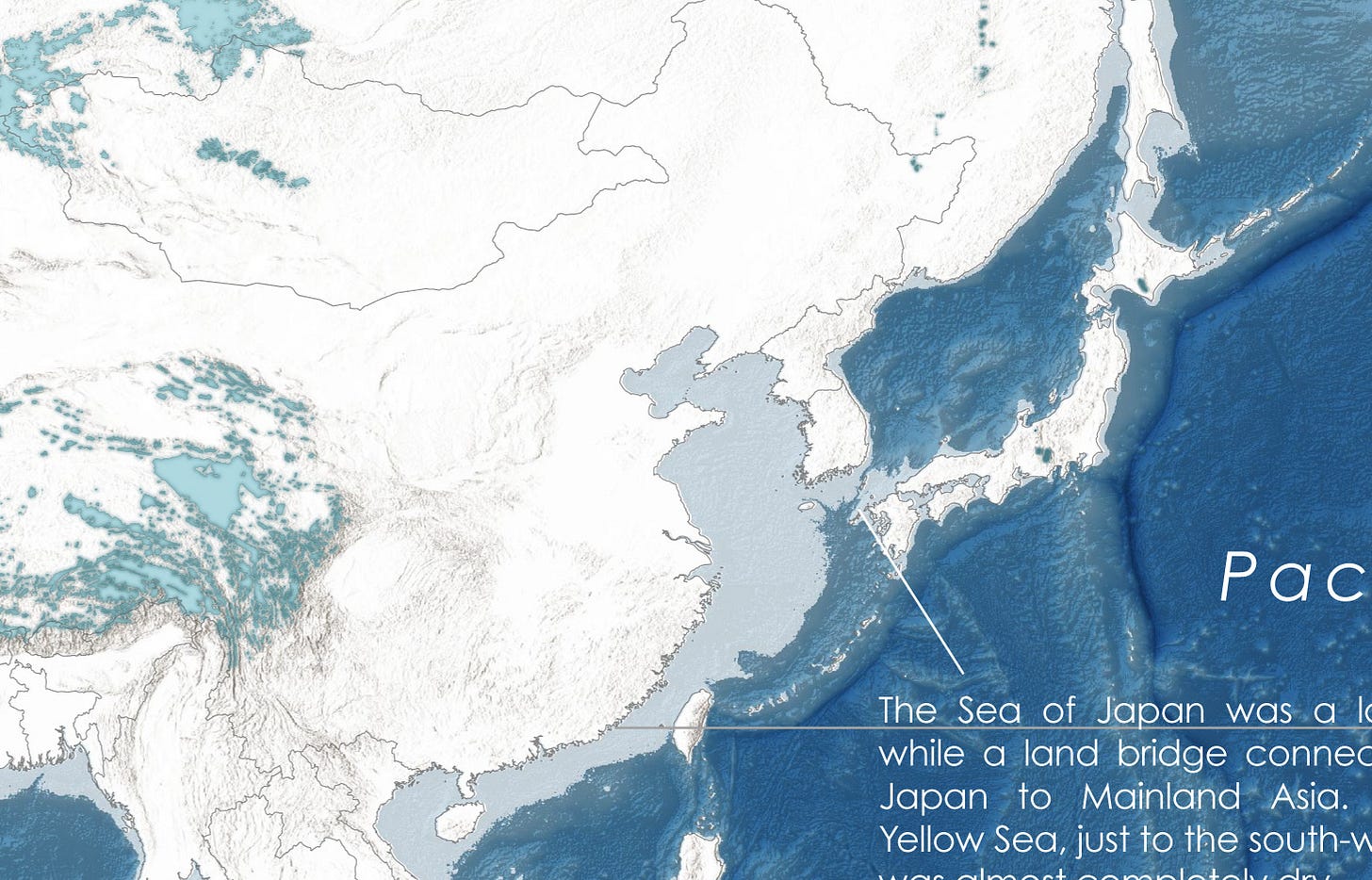

Just as Doggerland shows how humans reached the British Isles, the expansion of the eastern coasts of Asia made it possible for Taiwan and Japan to be connected to the continent. This allowed the first humans to reach these islands some 25,000 years ago.

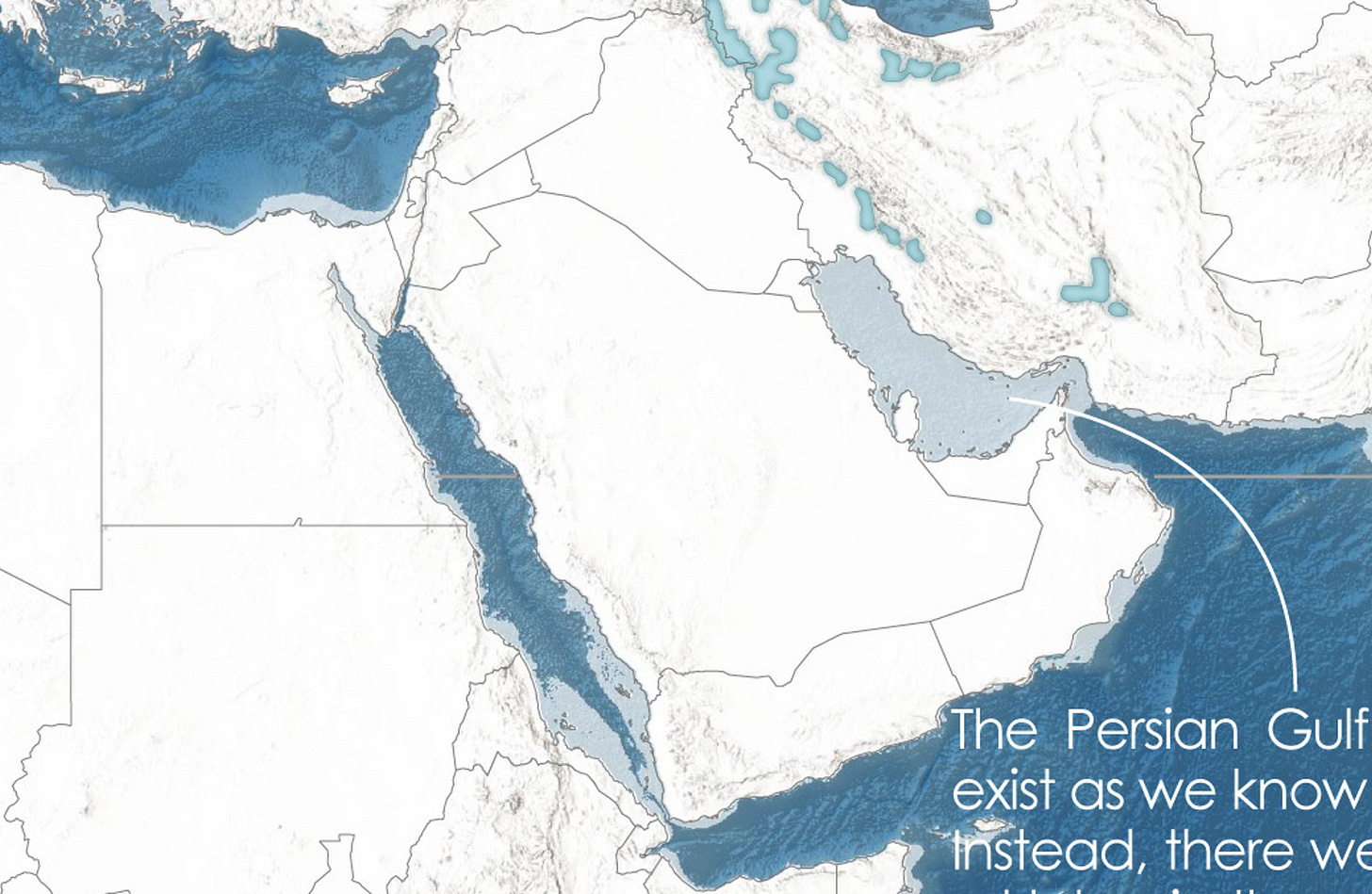

The Persian Gulf ceased to exist for a time, although it is believed that the region was too arid for anything apart from desert to arise. The Red Sea, although it also appeared to be on the verge of disappearing, remained perfectly connected via the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb. After all, at its deepest point, it is over 300 metres deep.

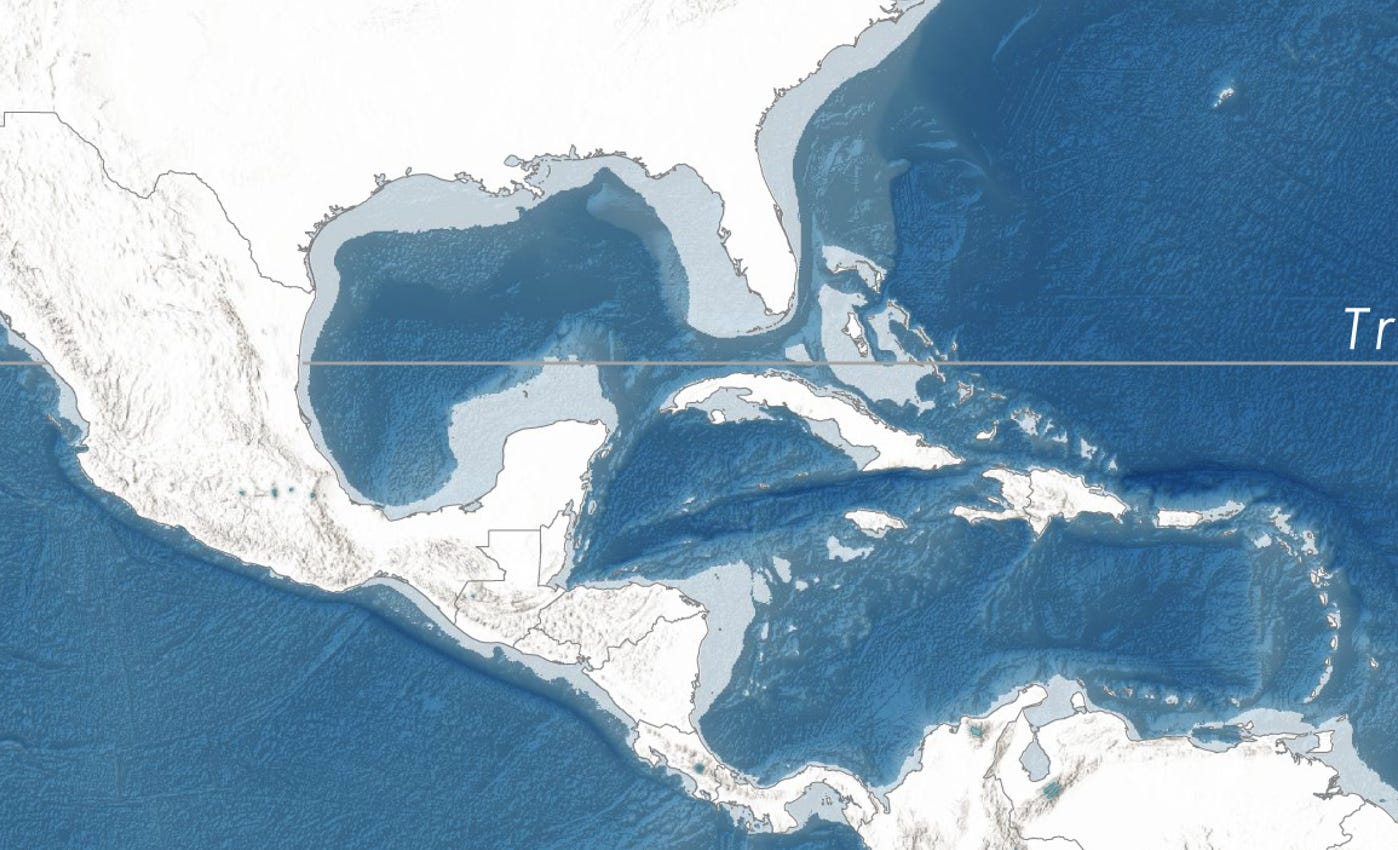

The Caribbean and Central America saw their size increase substantially. The Yucatán and Florida peninsulas increased significantly in size, reducing the size of the Gulf of Mexico. The smaller gulfs of Panama and Venezuela disappeared completely. But perhaps most curious is how the Bahamas became the second-largest island in the Caribbean, smaller than Cuba and larger than Hispaniola.

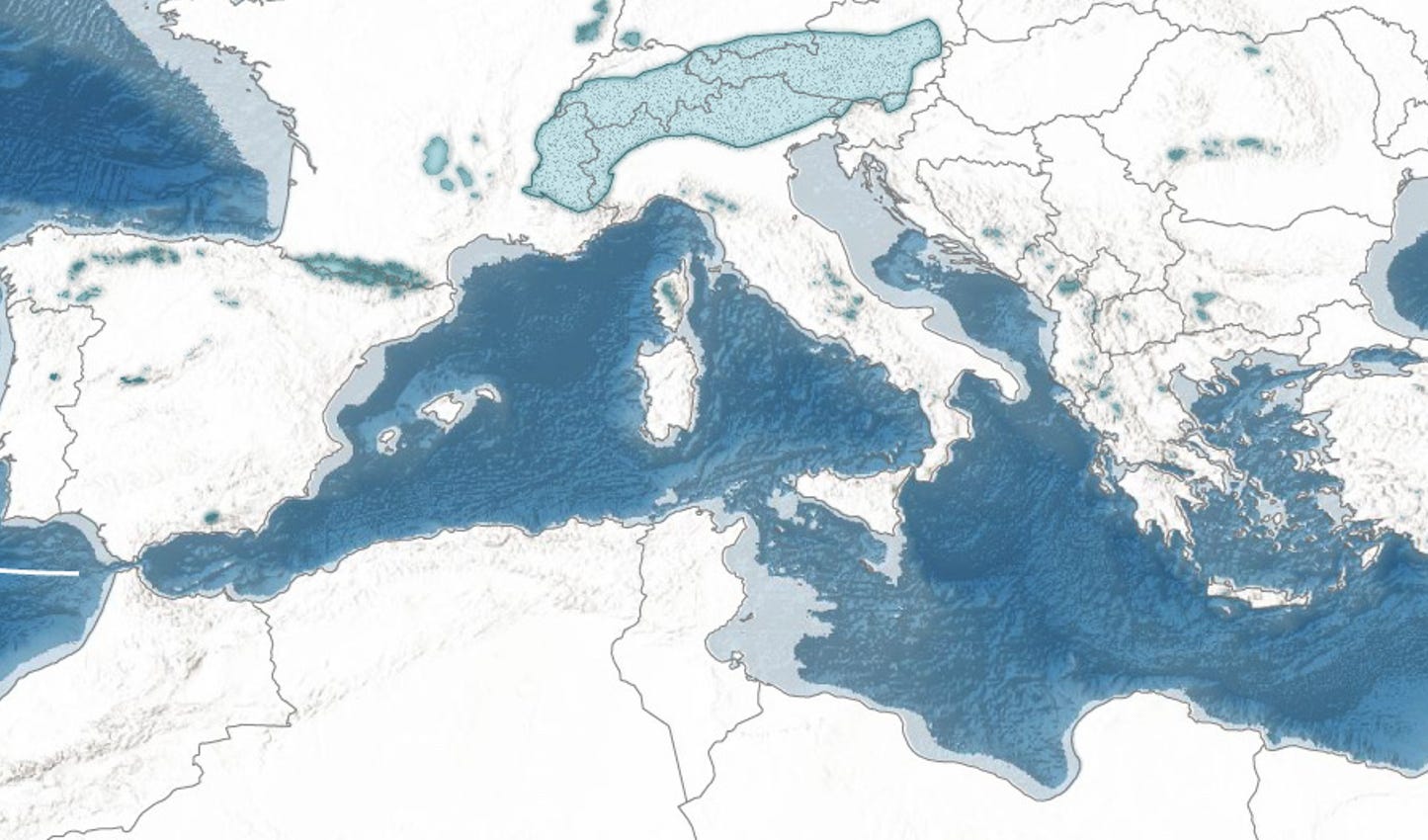

The Mediterranean Sea also saw its size reduced, especially noticeable in the Adriatic Sea, almost half of which disappeared. The coasts of Tunisia, France, and Spain advanced significantly, but perhaps not as significantly as the connection of many Greek and Turkish islands to the mainland. If you look closely, what happened during this period is very similar to what was planned with the Atlantropa project.

Tierra del Fuego ceased to be an island. The coasts of Argentina and Uruguay advanced hundreds of kilometres, and the Falkland Islands were unified into a single island. And well, a new island would also have appeared, corresponding to part of the current Burdwood Bank, everything that is less than 100 metres deep.

Finally, as the icing on the cake, I leave you with another map illustrated as if it were a physical map which, in addition to the land masses and glaciers, also incorporates the lakes that existed at that time.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

We have managed to increase the planet’s temperature by just over one degree in only a couple of centuries. To put the data into context.

Chukotka is the autonomous district of Russia that occupies the easternmost area, separated from Alaska by the Bering Strait.

This landslide occurred off the coast of Norway, and the volume was such that it raised a region the size of Iceland by 35 metres. As a result, there were tsunamis that reached up to 20 metres in the Faroe Islands.