Atlantropa, a plan to connect Europe and Africa

Herman Sörgel's grand project to drain part of the Mediterranean and flood part of the Sahara to “unite” Europe and Africa.

Who doesn't like a mega engineering project? Well, I suppose not everyone, but I admit that they really captivate my attention. A landmark that many of us may have in mind as a starting point is the Great Pyramid of Giza, built by the Egyptians more than 4,600 years ago. A building that reached almost 150 metres at a time when architecture and construction were still very rudimentary. Two millennia later, the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal built magnificent multi-level gardens in Nineveh, in a place where water was scarce. To achieve the necessary irrigation, he also had to create a fantastic network of canals to transport water over more than 50 kilometres1.

The Romans popularised great engineering works and took them to all corners of their empire, such as my beloved Aqueduct of Segovia. Centuries later, with the industrial revolution and the creation of modern states, a new era of major engineering projects began. There were iconic bridges, such as the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco and the Vasco da Gama Bridge near Lisbon. There were also canals that improved world trade, such as the Suez Canal and the Panama Canal. Some of these projects were as inconspicuous (but no less impressive) as the Delta Plan, an impressive system of sluices, locks, dykes, and barriers through which the Netherlands continues its battle against the sea2.

In addition to all these projects that were built, there were many brilliant minds who conceived great projects that were never built. An iconic example was Frank Lloyd Wright, who in 1957 presented a project to build a skyscraper one mile high, more than 1,600 metres. Another great example could the multiple times a bridge over the Strait of Gibraltar, or a tunnel beneath, that have been presented multiple times in the past 100 years, with the aim of connecting Europe and Africa by land.

And it is precisely in relation to the latter that I want to tell you a story today. It is about a macro-project designed during the Roaring Twenties to partially drain the Mediterranean Sea and thus connect the European continent with Africa.

Herman Sörgel, his life and historical context

It is difficult to understand the history and motivations of our protagonist without digging a little into his life and the context of his time. Herman Sörgel was born at the end of the 19th century in Germany into a wealthy family. His father, Hans Sörgel, was an important architect in Bavaria, rising to the level of nobility thanks to his contribution to the improvement of Bavarian society. This undoubtedly facilitated Herman Sörgel's access to a good education and influenced his choice to study architecture in Munich. During his early years after his student days, Herman was involved in the design and construction of government buildings, and even devoted much of his time to teaching and disseminating knowledge about the aesthetic considerations of architecture.

And then the Great War broke out.

The consequences of this war were brutal throughout Europe, causing many people to begin to see the world in a different light. The nationalism that had taken hold in Europe did not facilitate progress, as with each war, all the powers involved saw their influence wane in an increasingly globalised world. Pan-European sentiment seemed to be a solution, as it allowed for collaboration between European nations with a shared idea of progress.

In the mindset of the time, European society still had an idea of superiority that continuously dominated any discussion in the public sphere. Pan-European unity and Eurocentric sentiment still left room for colonialism in Africa to continue, albeit with benefits for all Europeans, without nations fighting each other for control of the African continent.

In this context, the union of Europe and Africa into a single geopolitical entity made sense. This new entity would stand as a counterweight to the threat from America in the west and Asia in the east. The only problem, in Herman Sörgel's mind, was the great separation represented by the Mediterranean Sea and how it limited the achievement of this ideal. Sörgel, who was a creative engineer, had a great idea to which he devoted the rest of his life.

Atlantropa

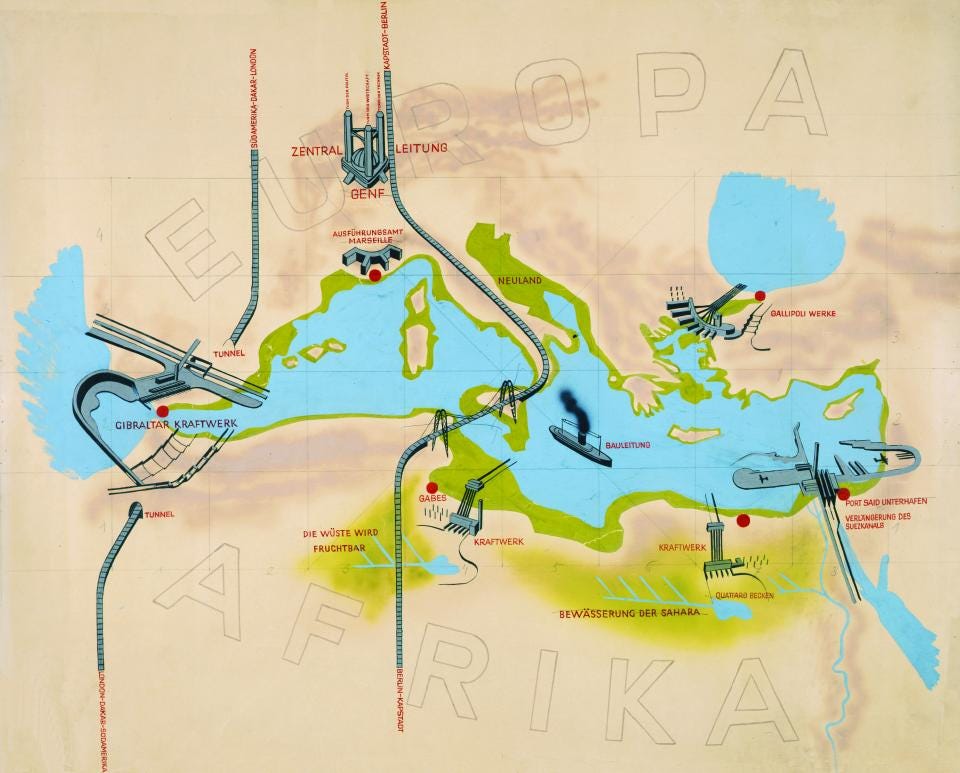

Draining part of the Mediterranean and connecting Africa with Europe was Sörgel's great project, which originally sought to solve many of the problems of his time. It aspired to be a reason to preserve pacifism and promote the union of European peoples, while allowing Europe to continue colonising Africa without internal tensions. From 1927 onwards, he began publishing articles in various magazines covering parts of the idea, until it was presented in its entirety at an exhibition in 1932.

The idea began with the creation of a dam in the Strait of Gibraltar, through which it would be possible to start draining the Mediterranean and gain territory. The new land that emerged would facilitate the interconnection between Europe and Africa, while creating new channels that would maintain the transit of ships through the Mediterranean Sea and increase the irrigation of desert areas.

As if this were not ambitious enough, Sörgel, in an attempt to become as respected an architect as his father, also aspired to solve Europe's energy problem with the growth of industry. By the beginning of the 20th century, it was already known that fossil fuels were a finite energy source. The consumption of coal and oil at that time was much greater than the capacity of known reserves, so many already predicted that new energy sources would be necessary. Sörgel's project included a multitude of macro-hydraulic dams which, according to his calculations, would be capable of supplying energy to the entire European continent.

The details of the project

Since the presentation of Atlantropa, and throughout the rest of his life, Herman Sörgel wrote more than a thousand articles and gave several presentations to publicise his project and get states to build it. As you may suspect, this came to nothing, as none of these dams were built in the Mediterranean, but we are left with many details.

Let's have a look at some of them.

This is the great dam of the Strait of Gibraltar. The aim was to lower the water level of the Mediterranean Sea by 100 metres. The idea was that the water would gradually lower due to evaporation, gaining territory in all coastal areas. This 35-kilometre-long dam would also be the main source of energy for the entire project, as it would maintain a flow of water from the Atlantic Ocean, allowing all that hydroelectric energy to be extracted.

With this dam, by reducing the depth of the strait, a tunnel would also be created to link Spain and Morocco by rail. This tunnel was envisaged as the key to establishing a route between Paris and Dakar, which would be used to transport goods extracted from the French colonies and distribute them quickly throughout Europe.

The Sea of Marmara would also have a dam in the Dardanelles Strait. The sole purpose of this dam would be to maintain a difference in level between the two large bodies of water (the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea), therefore serving as a hydroelectric power station to supply part of Eastern Europe with the necessary energy.

This third dam, stretching from Sicily to Tunisia, would only be built once the water level in the Mediterranean had already fallen by 100 metres. The aim of this dam would be to lower the entire Eastern Mediterranean Sea by another 100 metres. This would make more territory available in this area of the Mediterranean, and a third hydroelectric dam to be built to supply all of Central Europe with the necessary energy. Similar to the Gibraltar dam, the Sicily dam would also facilitate the construction of a second tunnel to establish a railway line from Berlin to Cape Town.

Sörgel's project was also aware of the effects it could have on international trade. The Suez Canal, which had been completed in 1869, had been a major boost to trade throughout Europe by minimising transport expenses between Europe and Asia. For this reason, the plan also considered extending the Suez Canal to cross all these new emerged lands and gradually lower the ships to the 200-metre depth of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea once the project was completed.

The plan also included the preservation of major European icons, such as Venice. Once the Adriatic Sea had descended 200 metres, Venice would be more than 1,000 kilometres from the coast and completely dry. For this reason, Sörgel proposed a series of dykes to help preserve the water around the city of Venice and, to maintain trade, the creation of a canal from the Bay of Venice to the Eastern Mediterranean Sea.

Beyond the Mediterranean

But the great Atlantropa project went far beyond the Mediterranean Sea. It was not only the idea of connecting Europe with Africa to facilitate colonialism, but also to increase the overall value of the African continent and its capacity for development3. For this reason, Sörgel also devised a large dam on the Congo River, around Kinshasa and Brazzaville, to create an artificial lake and supply the entire African continent with hydroelectric power.

The idea began with the new Lake Congo, but was not limited to it. This lake would have an almost unlimited supply of water, thanks to tropical rains, so it would be connected via the Ubangi River to the Lake Chad basin. It would allow the ancient Lake Mega-Chad, in the southern part of the Sahara, to be enlarged and indirectly restored. This new freshwater lake would be key to creating a new network of irrigation canals that would help sustain vegetation and crops throughout the Sahara.

These new lakes were planned to be connected by multiple networks of canals that would facilitate navigation and reduce the cost of transport to and from many of the new European colonies. The most remarkable of all would be the new Erg Canal, which would link the current coast of Tunisia with Lake Chad, crossing the most extensive dune fields in the Sahara Desert. In a way, Sörgel intended to replicate in West Africa the network of lakes and rivers in East Africa, which had so successfully facilitated the progress and advancement of such memorable civilisations as the Egyptian.

As previously stated, despite his attempts to be a pacifist, Sörgel was a child of his time and had a Eurocentric and colonialist mindset, so he never raised the important issue of creating large artificial lakes: all the citizens who would be displaced and deprived of their land for the sole benefit of Europeans.

Herman Sörgel's more than 1,000 publications came to an end in 1952, when he died in a traffic accident. Despite his perseverance, his plans were hardly heard and there were never any firm consideration to undertake any of them.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

The British Museum website has an excellent article describing these gardens. In fact, it is quite possible that the ancient wonder of the Gardens of Babylon was actually a myth based on these gardens in Nineveh.

This article discusses the project, which took four decades to build. I may talk about it in the newsletter one day because there are some very cool maps about it.

Always according to the European colonialism.

Great article. I love these kind of pie-in-the-sky, but carefully worked out schemes.

I suppose all those people flooded out in central Africa could have been put to work in the new cotton fields of the Sahara.

Never heard of him. Thank you. Wild stuff makes China mega canal projects look like kindergarten. But then they get built.