The other wonders of the Ancient World

Beyond the canonical list of the Seven Wonders, throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages, many lists were drawn up that included other equally impressive works.

Last week, I wrote about the story behind the seven wonders of the ancient world. In addition to briefly recounting how each of them came to an end, I also mentioned how arbitrary it was to choose those seven wonders and not many of the other possible ones. In ancient times, there were many lists, and the consensus among them was far from absolute.

If you are at all curious, you will wonder what wonders are mentioned in other lists that did not make it into the canon. And yes, that is the same curiosity I have had on multiple occasions. So I decided to dig into the lists explored by Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher in 1906, as well as all the lists explored by Ainhoa Miguel Irureta in her 2021 doctoral thesis1.

First and foremost, I have focused on the lists that appeared in Antiquity or the Middle Ages. Mainly because they are closest to the period to which they refer; all the lists from the Modern Age tend to build on each other and to be much more repetitive.

With that in mind, the eight wonders I mentioned in last week’s article are indeed the ones that are mentioned most often when analysing the data. However, not all wonders are mentioned equally. The Pyramids of Egypt2 and the Colossus of Rhodes appear on the vast majority of lists, while the Statue of Zeus at Olympia3 and the Lighthouse of Alexandria4 appear on less than half. The Colosseum in Rome is also mentioned in a significant number of lists, although I have omitted it because all the lists that include it are modern.

That said, I will focus on the rest of the wonders that are mentioned, selecting the seven that appear most frequently.

The Capitoline Hill

The Capitoline Hill in Rome, the city of Rome as a whole, or even in some cases the Colosseum, is the non-canonical wonder that appears most frequently in classical and medieval sources. Of course, its appearance coincides with the rise of the Roman Empire and the cultural nationalism that sought to elevate Rome and its most important monuments to the same level as the wonders of more distant places. Cassiodorus, a 6th-century Italian author, even claimed that Rome was a wonder far superior to any other described in books, which had only failed to achieve the same status because it came later in time.

The construction of the buildings on the Capitoline Hill, the most praised in the lists of wonders, dates back to the 6th century BC. Among all the buildings, the temple dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus stood out, as did the complex of fortifications that protected the hill. Of the seven founding hills of Rome, the Capitoline was the one with the greatest religious and political significance. This architectural complex did not have a single end, as it suffered multiple fires, reconstructions, and abandonments that caused it to lose its grandeur.

Temple of Jupiter in Cyzicus

Cyzicus was an ancient Greek city in Anatolia, next to the present-day Turkish city of Bandırma, on the coast of the Sea of Marmara. There stood the Temple of Jupiter, also known as the Temple of Hadrian. The temple was one of the most important in Asia Minor, built entirely of white marble and with dimensions comparable to those of the Temple of Artemis. It is possible that the only reason it failed to make it onto the canonical list was the choice of the Temple of Artemis, with which it had much in common.

Even so, perhaps the most interesting thing about this building was not its size, but the architectural engineering behind its construction. According to Pliny the Elder, the temple had a mechanism made of gold threads that allowed light and air to enter the temple through the joints in the walls. Like many buildings in the area, successive earthquakes and lack of maintenance eventually destroyed it around the 5th century AD. However, as shown in the image above, there are still impressive remains that attest to the grandeur of the temple.

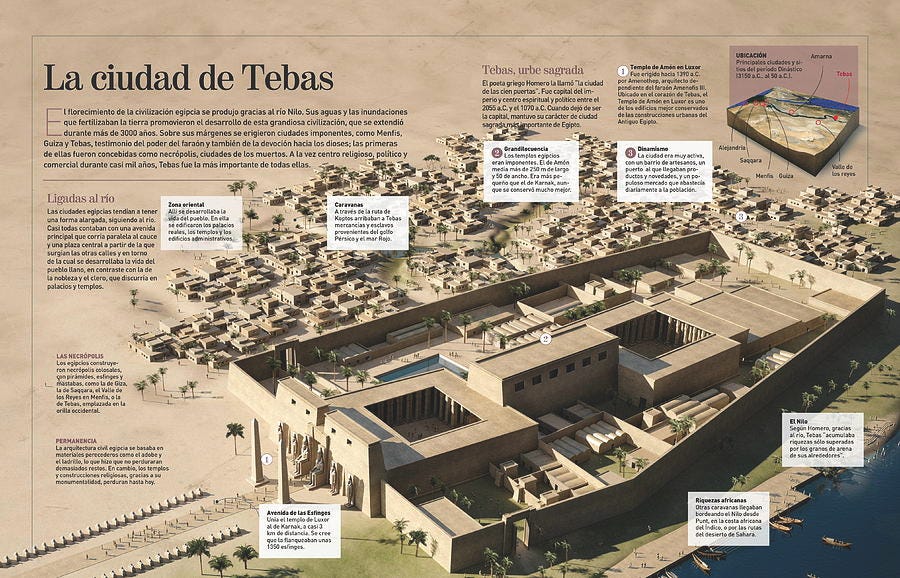

Thebes, the city of a hundred gates

With the archaeological work that has been carried out in Egypt over the last two centuries, it is easy to appreciate the grandeur of this wonder. Thebes of the hundred gates5, was the capital of the New Kingdom of Egypt and corresponds to what we now know as Luxor, the city that was built on the ruins of Thebes. As with Rome or Babylon, the fame of Thebes was not limited to a single building or monument, but to the city as a whole, with its many temples, walls and memorable colossi.

Today, anyone travelling to Egypt can enjoy the Temple of Luxor, shown in the image above; the Temple of Karnak, with 134 columns and multiple obelisks; and the Avenue of the Sphinxes, with more than a thousand sphinxes stretching over three kilometres, connecting the Temple of Luxor and the Temple of Karnak. I was fortunate enough to visit it a few years ago and can confirm that it is one of the most incredible places I have ever been to. And despite the grandeur of its ruins, what we see today is only a small part of what it was at its peak.

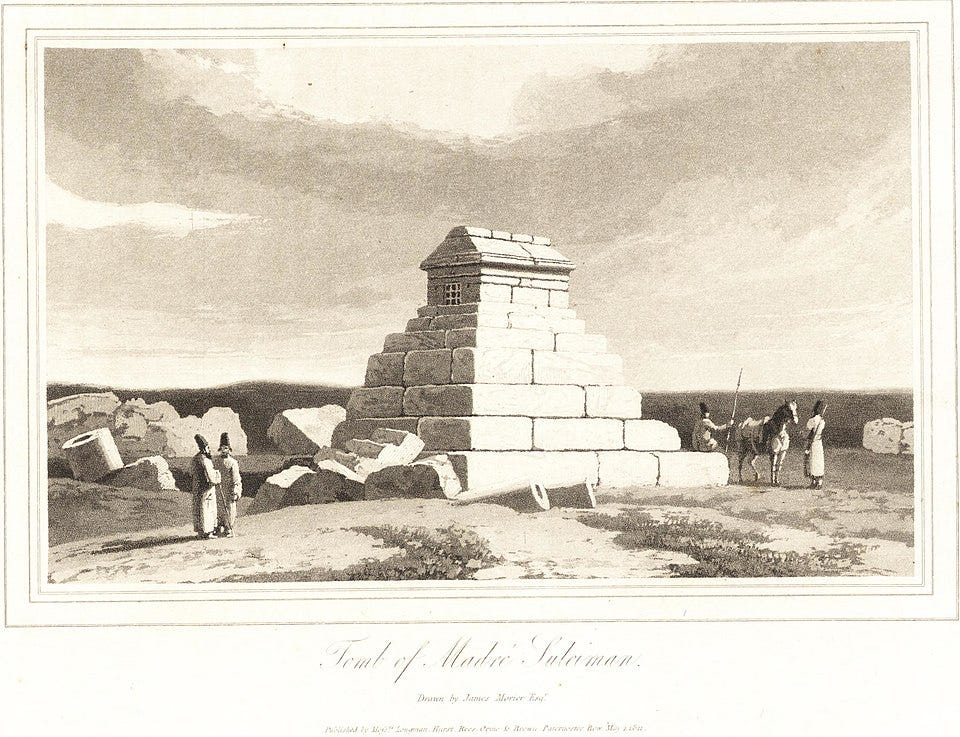

Tomb of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II the Great was one of the most important leaders of antiquity. Not only did he establish the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire, but he also expanded his power from the Indus River to the Dardanelles Strait. His tomb, eleven metres high and with artistic influences from different corners of his empire, became an emblem of the Persian people. This admiration spread throughout the Hellenistic world and earned it a place on many lists of wonders of the ancient world.

The funerary monument dedicated to Cyrus the Great has been preserved almost perfectly to this day, which has helped to keep the myth alive. Today, it can be visited at the Pasargadae site, 100 kilometres from Shiraz, in southern Iran. UNESCO recognised the value of the Pasargadae complex, declaring it a World Heritage Site in 2004.

Speaking of Cyrus, it is worth mentioning that Cyrus’ Palace in Ecbatana also appears on many lists, replacing the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. That palace was repeatedly described as a building constructed with stones of different colours joined together with gold. This luxury, which brought fame to the palace, has not been corroborated by any archaeological evidence to date.

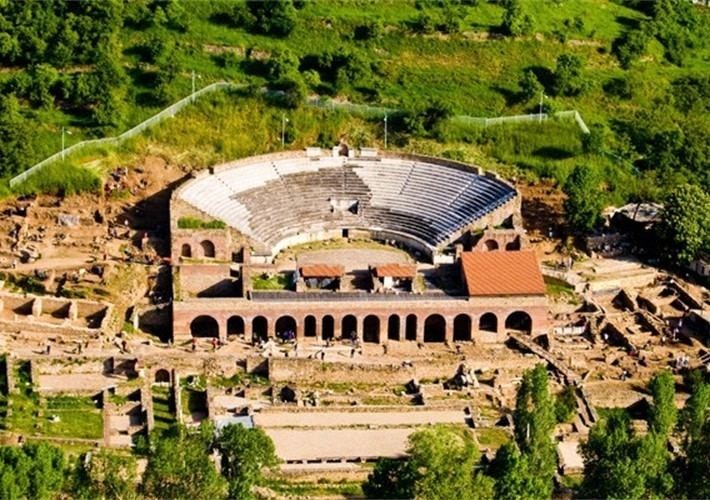

The Theatre of Heraclea Lyncestis

In southern North Macedonia, on the outskirts of Bitola, stands one of the many theatres built in Ancient Greece. If you visit it today, you can appreciate the typical acoustics of a medium-sized Hellenistic theatre, without any monumental features that make it more interesting than others. So why was it included in many lists of wonders of the ancient world? We owe this to Gregory of Tours, who included the theatre in his list of wonders in the 6th century, eight centuries after its construction.

To justify its inclusion, Gregory of Tours claimed that this theatre was carved directly into the mountain, so that the entire theatre was formed from a single piece of marble. He was not only referring to the seats, but also the walls, arches and sculptures, which were all part of the same rock. Of course, none of this was true at any time, but this example shows how mythical the stories behind many of these wonders are.

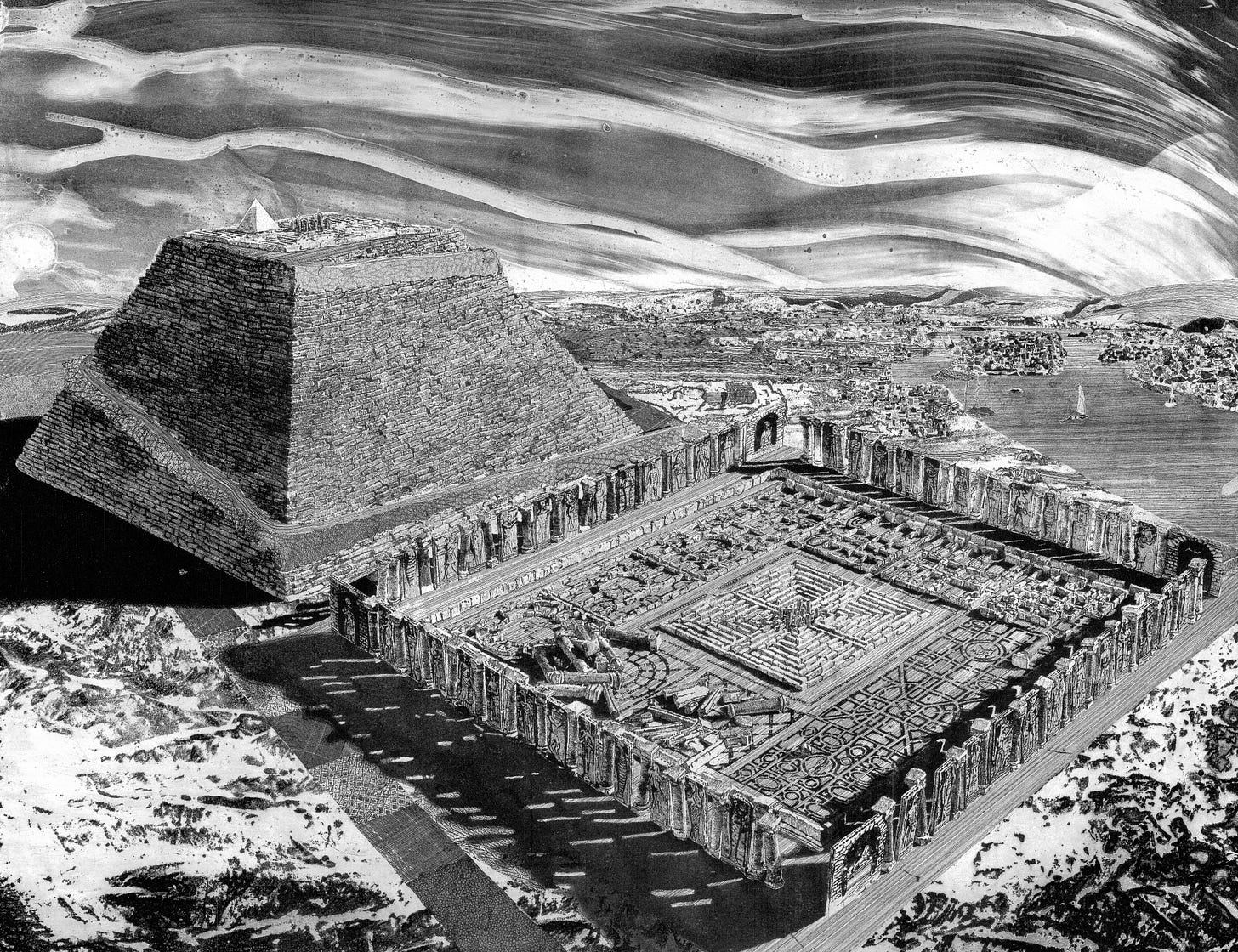

The Labyrinth of Egypt

Of all the wonders I bring you today, this is by far the one that fascinates me the most. It is a construction dating from 1850 BC that was located next to the pyramid of Amenemhat III in Hawara, Egypt. According to Herodotus, it was a complex of twelve covered and interconnected palaces, with more than three thousand rooms and multiple courtyards built on two levels, one of them underground. It was also completely surrounded by monumentally sculpted white marble columns. According to later authors, such as Pliny the Elder, this labyrinth served as inspiration for the creation of the Labyrinth of Crete, which is why it possibly gained more popularity in Classical Antiquity.

Archaeological remains of the labyrinth have been found next to the pyramid of Amenemhat III, although these are limited to sculptures and columns. It is believed that this wonder of antiquity was gradually dismantled during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, although there is no consensus on when it disappeared completely.

It is worth noting that, of all the non-canonical wonders, this is the one that possibly appears on the most lists during the modern age. In fact, the fascination with this wonder was not only mine, but also that of people like Athanasius Kircher, who drew this map of the labyrinth following the descriptions of various authors of Antiquity.

The Statue of Bellerophon in Smyrna

Bellerophon was a hero of Greek mythology who, among other feats, managed to kill the Chimera and ride Pegasus. His statue in Smyrna6 became the wonder that replaced the Zeus of Olympia in the lists of wonders when Christianity prevailed in the Roman Empire. This not only eradicated paganism from the lists of wonders, but also included a reference that could easily be related to Christian warriors such as St. George.

The first mention came from Cosmas of Maiuma, who described it as a metal statue of Bellerophon riding Pegasus, balanced on the wall of Smyrna. Later descriptions, such as that of the Venerable Bede, were much more fanciful, claiming that the iron statue was suspended in the air without the need for chains, thanks to the great power of the magnetic stones that surrounded it.

This wonder was tremendously popular during the Middle Ages, but beyond the accounts of various writers, no other ancient source or archaeological record has been found to suggest that anything remotely similar ever existed.

Epilogue: more wonders

The various lists contain a multitude of other wonders, some of which will surely be familiar to many of you. Among those that are still preserved and can be visited, either in their original location or relocated, are the Pergamon Altar on the Acropolis of Pergamon, the Colossi of Memnon and the Theatre of Myra.

Of many others, only a few archaeological remains or historical records remain. This is the case of the Athena Parthenos, the Sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus and the Altar of the Horns of Delos.

And, of course, many of the wonders are similar in nature to the Gardens of Babylon or the Statue of Bellerophon, such as Noah’s Ark, Solomon’s Temple, and the Labyrinth of Crete.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

If you are interested in the wonders of the ancient world, Ainhoa’s doctoral thesis will be of great interest to you. You can read it here, in Spanish, I’m afraid.

Sometimes only the Pyramid of Khufu, other times the three great pyramids together.

It ceased to appear on the lists when Christianity became dominant in the Roman Empire, as it was considered a pagan wonder.

It was the last of the canonical wonders to start appearing on the lists of Antiquity, with Pliny the Elder, in the first century of our era.

The nickname ‘Thebes of the hundred gates’ has been used in many texts to differentiate Egyptian Thebes from Greek Thebes.

Nowadays, Izmir, on the west coast of Turkey.

Exceptional deep dive into the fluidity of historical canon. The Bellerophon statue replacing Zeus when Christianity took hold shows how cultural ideology directly reshapes what gets remembered as 'great.' Stumbled on a similar pattern once when researching how medieval cartographers selectively redrew trade routes to fit political narratives. The suspended iron horseman story has that same mythmaking energy.