The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

The story of how the list of the Seven Wonders was compiled, and what became of each of them.

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World have fascinated me since I was a child. I remember coming across them for the first time in a historical atlas at my parents’ house, and I know that I looked up information about them at the public library on numerous occasions. In a way, admiring those monuments of the past helped me to understand a little better the changing nature of history, with its golden ages and subsequent declines.

Over the years, I was surprised to learn that, in reality, the idea of the seven wonders of the ancient world is more or less a recent construct, the result of a limited understanding of the ancient world. With Alexander the Great and the expansion of the Hellenistic world, many Greeks visited places as far away as Persia, Mesopotamia and Egypt, each of them compiling their own list of iconic monuments. But generally, not because they were extraordinary places, but because they were considered sites that everyone should visit1.

In 1906, Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher compiled more than 18 lists that appeared in various ancient texts. What may surprise many of you is that only two of the lists contained the same distinctive buildings and that, between them, they listed up to 22 monuments in different corners of Anatolia, Persia, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece… and even Rome.

So how did we reach a consensus on the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World?

With the Renaissance, Europe became obsessed with the study of Antiquity. Classical aesthetics gradually became dominant in architecture and, at the same time, the search for the great monuments of antiquity continued. In 1540, the Spaniard Pedro Mejía published Silva de varia lección2, which included the first modern reference to the wonders of antiquity, although he himself mentioned that there were multiple lists with no consensus among authors.

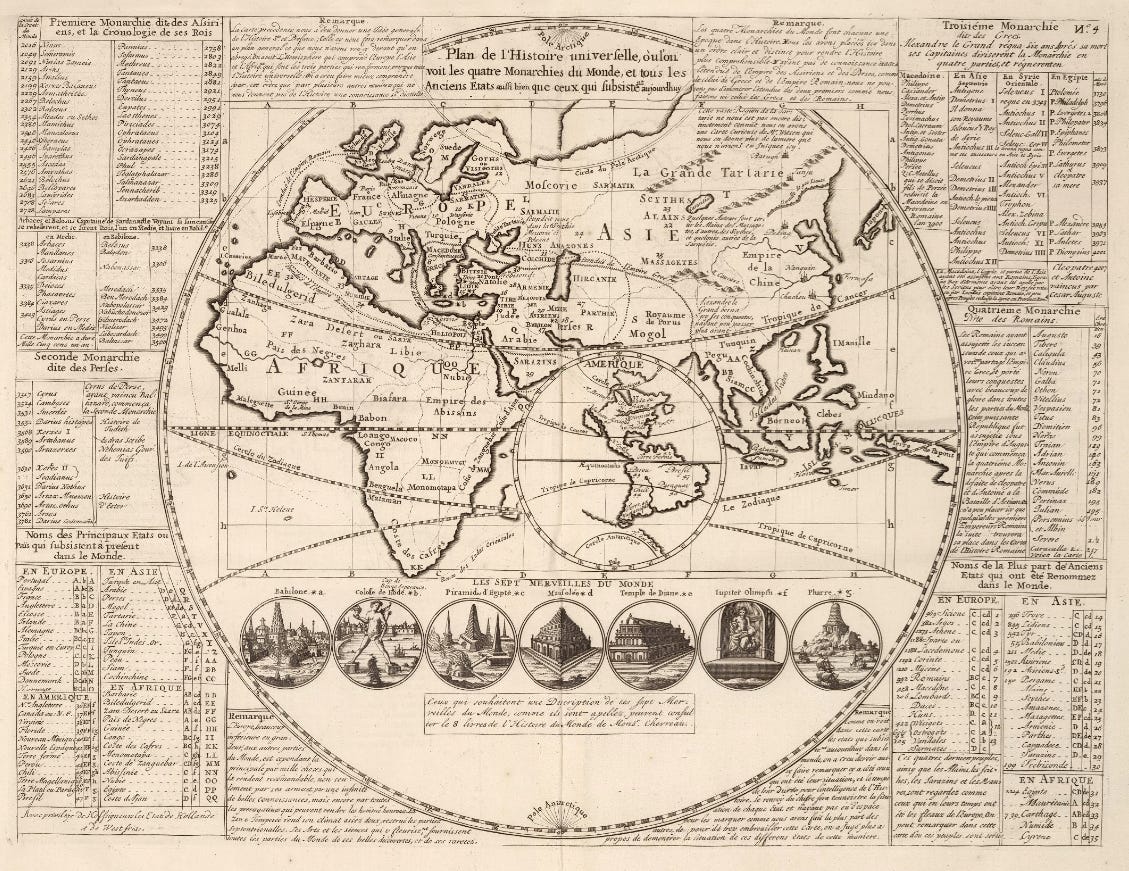

Taking this subtle idea as a reference, the Dutch painter Maarten van Heemskerck made a series of drawings depicting the seven wonders of the ancient world. Philips Galle turned these drawings into engravings, publishing them as Octo Mundi Miracula in 1572. They were a massive success throughout Europe and, as a result, established what we now know as the seven canonical wonders of the ancient world3.

Taking advantage of these engravings, today I will go through the brief history of each of these wonders, which only coexisted for a limited period of just over 50 years.

The Great Pyramid of Giza

Lofty wonders of pyramids, Pharaohs’ kings

Built stepped structures, as monuments for the buried,

They raised them, and showed the sun’s rays

To fall nearby, at the boundary of great Memphis.

It is by far the oldest of all the wonders on the list, having been built around 2600 BC. Surprisingly, it is also the only one that remains standing today. Although the canonical wonder refers exclusively to the Pyramid of Cheops, the largest of all, there are some lists that do refer to the Giza Pyramids complex, which also includes the pyramids of Khafre and Menkaure.

Originally, the pyramid stood 146.6 metres high, remaining the tallest man-made structure for 3,800 years4. It was also covered with white limestone, which gave the pyramid its characteristic shine. When this covering was lost, not only did it lose its shine, but it also lost a few metres in height.

As it is the only one of the wonders that has survived to this day, we can clearly see that Heemskerck never visited that place and did not have a good description of what the pyramids might have looked like. In a way, this difference serves to caution us about the rest of the representations, which are possibly imaginative and exaggerated.

The Lighthouse of Alexandria

For voyages, you built, Ptolemy, careful guide,

A lighthouse for the night, so when dark night lay still,

Bright torches, in the moon’s place, would shine light,

So that the Nile’s treacherous shores be approached more safely.

This marvel, as the verse says, was built during the reign of Ptolemy II (280-247 BC) on the island of Pharos, in the Nile Delta, near the city of Alexandria. It is estimated to have been about 100 metres high and, according to surviving descriptions, it was composed of three sections: a square base, an octagonal middle section and a circular upper section. At the top, the lighthouse had mirrors that reflected sunlight over long distances during the day. At night, a fire was lit, which also helped sailors locate the delta and enter the port of Alexandria safely.

Between 956 and 1303, three earthquakes caused serious damage to the lighthouse, leading to its partial ruin and abandonment. In 1480, the remains were reused to build the current Fort Qaitbey on the same site.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Imperious, with her husband’s head cut off,

Semiramis ordered lofty Babylon enclosed

With baked-brick walls, and gates with firm bitumen

One hundred added, and above them her noble tomb.

This is perhaps the most controversial of all the wonders. In his illustrations, Heemskerck focused on the wall of Babylon, although this wonder crystallised in the canonical list with the city’s other great monument described in other lists: the Hanging Gardens. If it were only for this, it would not be so controversial, but it is also the only one of the wonders with no consensus on its existence.

To date, we have nothing more than secondary sources without any archaeological remains. However, there are classical texts that describe the engineering work in great detail: landscaped terraces full of trees and shrubs, along with an irrigation system that used an Archimedes’ screw to harness water from the Euphrates. Recently, some historians, such as Stephanie Dalley, have suggested that the wonder actually referred to the gardens built in Nineveh by Sennacherib.

On the contrary, we do have archaeological remains of the walls mentioned by Heemskerck. Not only do we have evidence of the foundations of the walls5, but some monumental parts are preserved in great detail. And of course, I am referring to the Gate of Ishtar, which is currently preserved in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

The Temple of Artemis

An Amazon built this in Ephesus for you, Artemis, a sacred

Temple, a luxurious and great Asian ornament.

A marsh held its deep foundations, laid upon charcoals beforehand,

So earth might stand unmoved in a quake.

The Temple of Artemis was located in the ancient city of Ephesus, now on the western coast of Turkey. It was renowned for its grandeur, although there is evidence that it was rebuilt at least twice, the last time after a fire in 356 BC. In its third phase, it remained standing for more than 600 years, until 391 AD, when Emperor Theodosius decided to close it down permanently. The building may have had already been damaged during the Gothic raids in 268 AD, but its final destruction did not take place until 401 AD.

Its third phase was the most grandiose of all. It is said to have been built entirely of marble, measuring 130 metres long, 70 metres wide and about 20 metres high. This is difficult to imagine, so it is better to say that almost all of its dimensions are twice those of the Parthenon in Athens, one of the most iconic buildings of this style preserved in Ancient Greece. In addition to its size, the Temple of Artemis also incorporated 127 columns covered in gold and silver, as well as multiple sculptures and motifs that made it a unique temple.

The Statue of Zeus at Olympia

Elis, mother of Olympia, who signals Achaea

With famous games and records, she houses wonders:

Showing Phidias’ Zeus, carved from white ivory,

Whose hair and nod once shook Olympus.

Phidias is possibly the most renowned sculptor of Ancient Greece. Among other things, he was responsible for the reconstruction of the Acropolis of Athens, as well as the iconic statue of Athena that stood inside the Parthenon. But his masterpiece, according to all classical sources, was his statue of Zeus at Olympia. Standing 12.4 metres tall, the sculpture of the seated god occupied half the length of the temple’s hall. Zeus’ head was so close to the temple ceiling that it gave the impression that, if he stood up, he would break through the roof of the building.

It was built in 435 BC, and with this sculpture, Phidias had to solve the problem of the weight of the stone. To achieve this, he created a large wooden structure, on which he placed ivory plates and gold panels. The final decorations consisted of paint and ornaments of ebony, ivory, gold, and other precious stones.

Its magnificence is made even more evident by testimonies such as that of the Roman emperor Caligula, who requested that the statue be moved to Rome and that the head of Zeus be replaced with his own. We know that this did not happen, but it is not known exactly what happened to it. Some sources suggest that it was destroyed along with the temple during a fire in 425 AD, while others suggest that it may have been moved to Constantinople and destroyed in another fire in 475 AD. Whatever the case, the statue has not survived to the present day, and there are no records of its existence since the 6th century AD.

The Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus, said to be 700 cubits,

Equal in mass to a tower, under the Sun’s name,

Was made of hollow bronze, with a cavern of stone inside

Among the Rhodians it received sacred honors.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing about this marvel is how it has been captured in the popular imagination. Historically, it has been depicted straddling the entrance to the harbour, forcing all ships to pass underneath it to enter and leave the city. The engineering studies in recent decades indicate that this would not have been possible, as the statue would have collapsed under its own weight.

However, the reality is no less impressive. It was built between 292 BC and 280 BC under the direction of Cares of Lindos and was intended to celebrate a victory against the Macedonian attack, although the statue itself was dedicated to the god Helios. At 33 metres, it was the tallest statue built in ancient times and, as if that were not enough, it stood on a platform another 20 metres high. To put these measurements into perspective, Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro is 30 metres high and stands on a platform only 8 metres high.

Its undeniable grandness was possibly also its weakness. An earthquake in 226 BC broke it at the knees, just 54 years after its construction. There were proposals to rebuild it, but these were never carried out, and its ruins remained on the ground as an attraction for more than eight centuries, which is possibly what Heemskerck refers to in the foreground of his drawing. When the Arabs conquered Rhodes in 653 AD, the remains were sold to a merchant, ending the history of this marvel.

The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus

From Mausolus’s grave, his wife drew warmth,

Imploring lifelong devotion to his ashes.

Setting an example she erected a tomb, on which

Artists carved the greatest statues from marble.

Mausolus was satrap of Caria from 377 BC to 353 BC, and upon his death, it was decided to build him a tomb. Up to this point, this was probably what happened to any other ruler who died in those times. But Mausolus, as if he were an Egyptian pharaoh, had already begun planning his tomb before his death. His sister ensured that it was completed in 351 BC. The funerary monument was of such calibre that it not only became one of the Seven Wonders of the World, but also gave its name to the term mausoleum.

The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, named after its location in the capital of Caria, was 46 metres high and featured sculptures by the best artists of the time. Given its location in Anatolia, it combined Greek, Egyptian and Persian influences, achieving a unique appearance. The tomb remained standing until the 15th century, when it was destroyed by multiple earthquakes. Part of its remains form part of the current Bodrum Castle, rebuilt a few years after the destruction of this marvel.

Bonus: The Colosseum in Rome

To these is added by the poet whose birth Bilbilis boasts (i.e. Martial),

The sacred glory of the imperial amphitheatre:

A structure that mimicked the globe’s round shape,

Hollow, it held the crowds and staged their games.

All of Maarten van Heemskerck’s drawings have a certain aura of fantasy. The fantasy of someone who draws from vague descriptions found in old books and has never had the opportunity to visit those places. All except for the eighth drawing with which he ends his work, the Colosseum in Rome.

Heemskerck did visit the Colosseum in Rome during his lifetime, as shown in one of his self-portraits. He was so fascinated by the building that he did not hesitate to include it in his personal list of wonders of the ancient world. Although on this occasion he did not show the building at its peak, but depicted it in ruins, as he had known it.

Despite being part of Octo Mundi Miracula, the Colosseum in Rome did not make it onto the canonical list of the seven wonders, possibly because it did not appear in any classical source. Even so, without Heemskerck’s trips to Rome and his fascination with the Colosseum, we might never have had this fabulous collection of engravings. And who knows, perhaps a list of wonders of the ancient world would have never been established to serve as a reference for what was once greatness, and of which not even ashes remain.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

There are also historians who speak of a possible mistranslation. The first lists were accompanied by the Greek term theamata (θεάματα), which means sights or places to visit, while later lists were accompanied by the term thaumata (θαύματα), which can be translated as wonder. The similarity between the two terms is what makes one suspect a possible translation error.

It is available in its entirety here. The book is written in Old Spanish and is extremely dense. To be honest, it is not even worth skimming through. It only mentions the wonders in chapters 32 and 33.

As is often the case with all knowledge centred on Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, the canonical list of the seven wonders is guilty of being Hellenocentric. When these lists were compiled, there were great monuments in other corners of the world, but these were unknown to the Greek authors, who focused all their attention on the territory once ruled by Alexander the Great.

This height was surpassed by the old St Paul’s Cathedral in London in 1087. It may also have been surpassed by the Kanishka Stupa in 200 AD, although there is no consensus on the actual height this structure reached.

More than 80% of the wall’s layout remains unexcavated.

Incredible work tracing how Heemskerck's engravings basically froze the canon in 1572! The fact that ancient sources listed up to 22 diferent monuments but we settled on seven becuase of one artist's drawings really underscores how contingent our historical narratives are. What's especially intresting is that Heemskerck never visited most of these sites, so our collective visual memory of ancient wonders is built partly on educated guesses and Renaissance imagination rather than direct observation.