Italian irredentism and propaganda

The history of Italian unification, the emergence of the sentiment of irredentism, and how it was used by fascism during the 20th century.

As I have commented occasionally, propaganda is a subject that fascinates me. In the same lines, I truly enjoy reading about nationalist myths and how they were constructed in each country throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. For a time, I was working in Naples, and there many colleagues shared with me their vision of how Italy became Italy, and many of the consequences of that historical process, of which I was completely unaware1.

With this background, today I am going to write about the history of the Unification of Italy, the birth of irredentist sentiment and how it became one of the fundamental pillars of fascism in Italy.

The Unification of Italy

Despite what is often thought, the unity of the Italian peninsula under one political entity has not been the norm throughout history. After the fall of the Roman Empire, fragmentation was the norm for over a thousand years. Powers shifted, external and internal forces formed their own states and fought among themselves, but none achieved the unity of the peninsula. Thus, at the beginning of the 19th century, Italy was still divided between the Kingdom of Sicily, the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Kingdom of Naples, the Duchy of Milan and the Republic of Venice, as well as other minor principalities.

Despite all the centuries of division, the culture and language of the different regions were still close, which facilitated the rise of nationalist movements throughout Italy in the 19th century. These movements sought unity, but also freedom from interference by foreign powers, which had been common for centuries and became more pronounced after the Congress of Vienna2. This sentiment was reinforced during the revolutions of 1848 which, despite their failure in Italy, served to emphasize that Italian nationalism was much more widespread than had been thought.

The first attempt at unification took place in 1849, when Austria easily defeated the Kingdom of Sardinia. This experience led Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour and Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Sardinia, to understand the need for a foreign policy that would position the Kingdom of Sardinia as a state capable of seizing power in Italy. The second attempt at unification began in 1859 and, in just two years, Cavour expelled Austria from northern Italy and incorporated Lombardy into his kingdom. With Austria off the board, Emilia-Romagna, the Duchy of Tuscany, Modena, Parma, and Lucca were voluntarily annexed.

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which grouped together the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily, initially opposed unification, although much of its population was in favour. To accelerate the process, Cavour appointed Giuseppe Garibaldi to lead the Expedition of the Thousand, which involved the landing in Sicily of 1089 war veterans. With the support of the like-minded population, they achieved the annexation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to the Kingdom of Sardinia.

As a result, the Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed on 17 March 1861, with Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia as king and Cavour as president of the Council of Ministers. However, unification still had two major outstanding issues. In 1866, Italy took advantage of a clash between Prussia and Austria to intervene in favour of Prussia and annex Venice, which was still under Austrian control. The final step came in 1870, when French troops withdrew from Rome and the Kingdom of Italy succeeded in incorporating the city and making it its capital.

Italia irredenta

A unified Italy was not enough, at least not for those who wanted all people of Italian culture to be part of the new nation. Parts of the historical possessions of the Republic of Genoa or the Kingdom of Sardinia, such as Nice, Corsica, and Savoy, were still part of France. Historical possessions of the Republic of Venice, such as Dalmatia, Istria, and Trentino, were still part of Austria. Thus, the idea of Italia irredenta, which can literally be translated as unredeemed Italy, was born, referring to all those lands that, according to the irredentists, rightfully belonged to the Kingdom of Italy.

The first organisations were formed a few years after unification, as was the case of the Associazione in pro dell'Italia irredenta (1877). From its formation, it was extremely critical of the new Italian government for having given up on the complete unification of Italy and leaving Trentino, Istria and Dalmatia under the Austrian power. It staged numerous protests against Austria and Italy, and even tried to organise an armed intervention in Trentino in 1879 to rectify the borders that had been imposed.

The signing of the Triple Alliance in 1882 between Italy, Germany, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire limited Italy's scope for irredentism. While the Italian government's interest in this alliance was partly to gain allies to confront France over the North African colonies, the irredentist movements interpreted it as a further stab in the back. It was a clear agreement with Austria, a country with pending territorial claims in the eyes of the irredentists. As a result, the discourse of the Associazione in pro Italia irredenta intensified. In 1889, the irredentism signed a manifesto accusing the Italian government of having left Italy at the mercy of foreigners, which was received with a strong censure of the publication and an immediate ban on its promotion and distribution. Tension continued to rise until 1891, when the Prime Minister ordered the dissolution of the association. However, irredentism was kept alive by the Società Dante Alighieri, created in 1888 to preserve the Italian language and culture3.

At the beginning of the 20th century, irredentism found new allies in important politicians from across the spectrum, such as Gabriele D'Annunzio, leader of the extreme right, or Cesare Battisti, a member of the Socialist party. This rise of irredentism and Italy's strong trade relations with France and the Russian Empire were the main reasons why Italy did not honour the defensive alliance with the Central Powers at the outbreak of World War I in 1914. At the end of the same year, Benito Mussolini founded the newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia in Milan as a means of pressuring the state to intervene in the war. The new medium was heavily financed by several Italian companies, thanks to which it carried out a strong campaign of awareness-raising and manipulation to get Italy to enter the war on the side of the Triple Entente4.

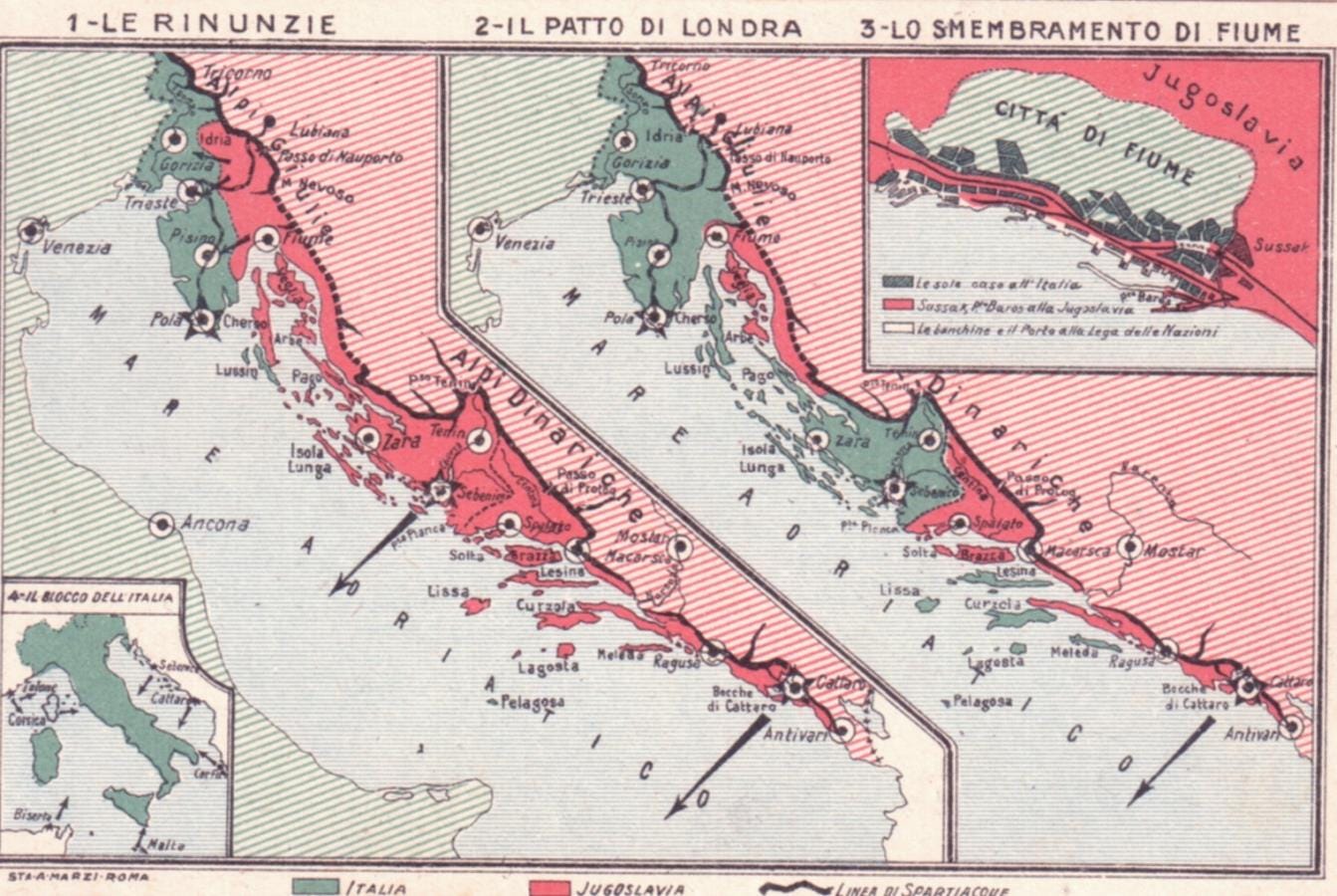

Before the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the Italian nation hoped that the Treaty of London, by which Italy agreed to join the First World War, would be honoured. It guaranteed that Italian cooperation would be compensated by the recovery of the historic regions of South Tyrol, Trentino, the Istrian peninsula and the northern coast of Dalmatia. At the Versailles negotiations, Italy saw the entire coast of Dalmatia given to Yugoslavia, a newly created country. The agreement with their French and British allies had been broken, and neither had defended Italy at the negotiating table.

This was a major setback for Italian nationalism and, despite the victory and territorial gains, there was growing discontent in society. D'Annunzio coined the term vittoria mutilata (mutilated victory) to refer to the unfair treatment Italy had suffered in the peace negotiations.

Greater Italy and Fascism

The reaction in Italy was quick. D'Annunzio's position found support, and he had no problems in recruiting more than 2,500 soldiers, with whom he took the town of Fiume5, on the northern coast of Dalmatia, near Istria, and proclaimed its annexation to the Kingdom of Italy. This action, known as the Impresa di Fiume, found strong support among Italian war veterans and nationalists, and a strong propaganda campaign led once again by Il Popolo d'Italia. In this context of international tension, Mussolini founded the political movement Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Fasces of Combat)6 in 1919, with which he ran for the first time in elections in 1919, with no success.

This failure marked a turning point in Mussolini's policy, and he opted for direct action similar to D'Annunzio in Fiume. Through Il Popolo d'Italia, the new Fascist movement supported a strong militia and, thanks to this, it found financial backing from companies linked to the arms industry. At the same time, it covered the success of the Impresa di Fiume and appealed to the newspaper's readers for additional funding to maintain control of the city. This money, due to the corruption of the newspaper, never reached D'Annunzio, but was used by the Fascist movement to reorganise itself and gain a better position for the 1921 elections.

The actions of Mussolini's new organisation were not confined exclusively to propaganda in the gazette, of which he was editor-in-chief. All this served as an important complement when he took advantage of the great military experience of a large part of the members of the movement. The arditi, Italian assault troops during the First World War, marked the emergence of squadrismo, a paramilitary movement associated with the Fasci that replicated the recognisable uniform of the arditi: the black shirt. This subtle propaganda campaign of association proved very successful in the more nationalist circles, as the assault troops were recognised as the true heroes of the war and were considered to be a point of reference in post-war Italy.

In the run-up to the 1921 elections, Mussolini radicalised his discourse and, in addition to irredentism, he embraced ultra-nationalism and the need for an expansionist imperialism that would restore Italy's greatness. The party obtained a better result, far from a victory, but enough to be part of the coalition government. Thanks to this, the Blackshirts began to operate with impunity as a militia associated with a ruling party: they forced out dissident civil servants; expelled local leaders of other parties; and dismantled Catholic and socialist organisations to replace them with fascist organisations serving a similar purpose.

The great show of power took place between 27 and 29 October 1922 with the march on Rome. For two days, all the militants and sympathisers of the National Fascist Party were called to take to the streets of cities all over the country and, above all, Rome. Around 25,000 people occupied railway stations and administration buildings, thus putting the position of King Victor Emmanuel III in check. To avoid an escalation of violence and a possible civil war, on 29 October 1922 the king stopped Prime Minister Luigi Facta from declaring martial law and asked Mussolini to form a new government.

Once in power, Italian Fascism focused on expansionist imperialism and the attempt to recapture Greater Italy, in part resembling the great successes of Ancient Rome. No longer limited to the claims of irredentism, it sought to recapture the entire Adriatic coast and, in addition, to occupy the entire coast of Libya and Tunisia. Shortly before World War II, this plan began to be implemented with the invasion and conquest of Albania in April 1939. Even after the outbreak of the war, almost all of this territory was occupied by the Italian army, although it was only a mirage for a few months. The United States and the United Kingdom quickly succeeded in crushing the aspirations of Italian imperialism and irredentism forever.

PS: I have omitted the idea of Risorgimento (Risorgimento), which is also relevant when talking about Italian irredentism. That concept, which is much used in Italy to speak of unification, draws a direct line to the unity of the peninsula in the time of the Roman Empire. As if the unity of Italy were the pure nature of the region and not the division of power that lasted more than a thousand years. The Risorgimento plays a fundamental role in irredentism and Italian nationalism, similar to the idea of Reconquista in the case of Spanish nationalism7.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

I would like to talk about this in more detail one day. The main complaint of my fellow Neapolitans was the promise that the unification of Italy would also unite the living conditions of the north and the south. The feeling of many southern Italians is that this never came true, and that inequalities increased, even though this is considered one of the main reasons why mafia organisations gained so much southern weight. It is a fascinating subject.

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 ended the Napoleonic wars and resulted in a division of Italy, with much of it under Austrian control.

This association would be the equivalent of today's Instituto Cervantes in Spain or Goethe-Institut in Germany, although in its early days it was strongly linked to Italian nationalism and irredentist movements.

The Triple Entente was the alliance of France, the United Kingdom and the Russian Empire, which confronted the Central Powers, the name given to the alliance of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Fiume corresponds to modern-day Rijeka in Croatia. Interestingly enough, both names mean river in their respective languages.

This party later changed its name to Partito Nazionale Fascista (National Fascist Party) in November 1921.

This is an interesting topic, so better for another day.

Savoy and Nice were not Genoese. Piedmont ceded them to France in exchange of French help in defeating the Austrians ti gain Lombardy and Veneto

Thanks for this. Perfect timing for me after a holiday in Sicily. The 1843 map is particularly useful.