The mines and catacombs of Paris

A tour of the mines beneath the city of Paris and how they became the famous Catacombs of Paris.

Paris is one of the most visited cities in the world, and it’s no wonder. It has such iconic tourist attractions as the Eiffel Tower, Notre-Dame, and the Arc de Triomphe, as well as must-see museums such as the Louvre and Orsay1. It is true that eating in its restaurants is expensive, but it is undeniable that it has a well-deserved reputation for its cuisine.

Despite all that, one of the places that interests me most in Paris is not visible at first glance. It is under the city, where galleries stretch for tens of kilometres, connecting different parts of the city.

The mines of Paris

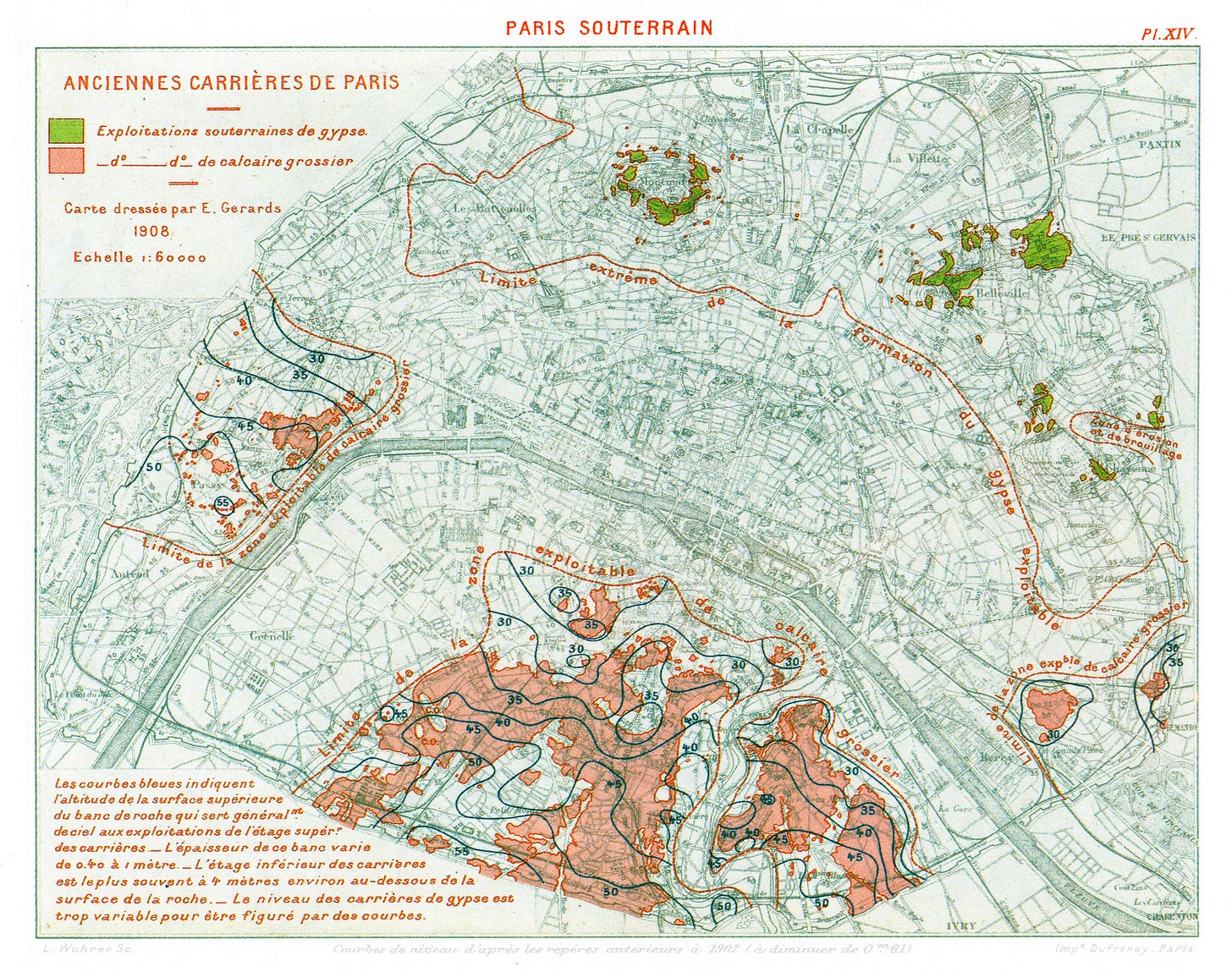

Paris was founded on land rich in minerals. The many rivers that flowed through this area during the last ice age eroded the land, exposing materials like gypsum, sand, and limestone, which were extremely valuable in ancient times for the construction of buildings and infrastructure. This mining activity is recorded in very early settlements, and it is known that it continued at least until well into the 15th century.

Surface veins began to become less abundant, and it eventually became necessary to be more creative to continue accessing the wealth of the territory. Underground mining deposits have existed in Paris since Roman times, although they did not get popular until there was an urgent need. Miners started to create vertical shafts throughout the city to access the deposits horizontally.

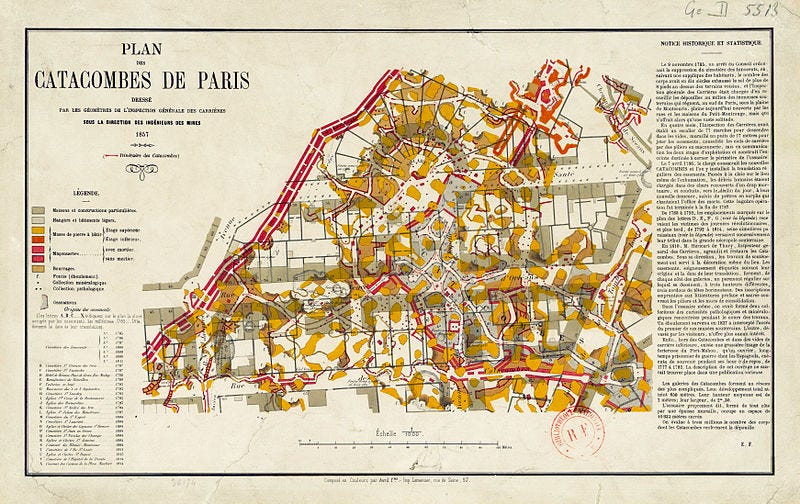

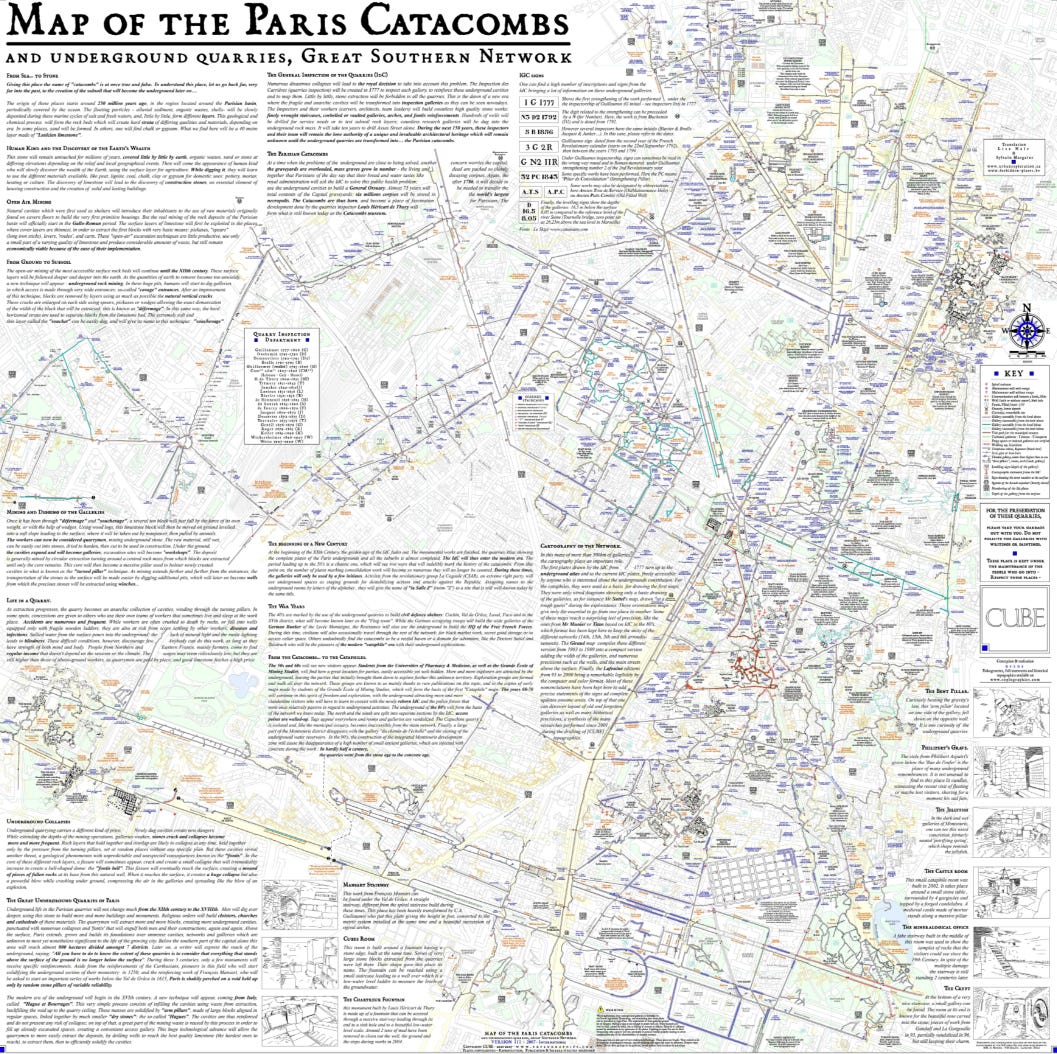

Given the depth of many of these excavations, it was necessary to create structures that would guarantee the safety of the deposits and allow materials to continue to be extracted. The most popular method was extraction through parallel galleries, which were connected to other perpendicular galleries, creating grids with columns of intact material that acted as supports. In the most unstable areas, additional pillars were also created to ensure that the ceilings remained secure.

That is why, over the centuries, a network was created organically under Paris that is unparalleled anywhere else in the world2. More than 280 kilometres of galleries still extend across the subsoil of Paris, even though mining was gradually abandoned during the 17th and 18th centuries. This neglect led to the collapse of 300 metres of a street more than 20 metres deep in December 1774. Three years later, the city government began the arduous task of securing all the underground structures and, in the process, began to catalogue this entire world that had once supplied the city with stone and had been almost completely forgotten.

The problem of medieval cemeteries

During the Middle Ages, with the rise of Christianity throughout Europe, plenty of churches were built. Many of them preserved the relics of saints as a form of worship, or were even built around them. This, combined with the fact that these buildings had been consecrated, was key to understanding how cemeteries became popular next to churches. In a way, being close to the house of God provided the purity necessary to protect oneself from evil and guarantee a good fate after death.

In cities with large populations, this soon became a problem. Around the year 1000, due to the rapid expansion of Paris, many of the churches and their respective cemeteries were surrounded by buildings and new citizens. These inhabitants frequented the nearest places of worship and, as good parishioners, also wanted to be buried in the same cemeteries as their ancestors.

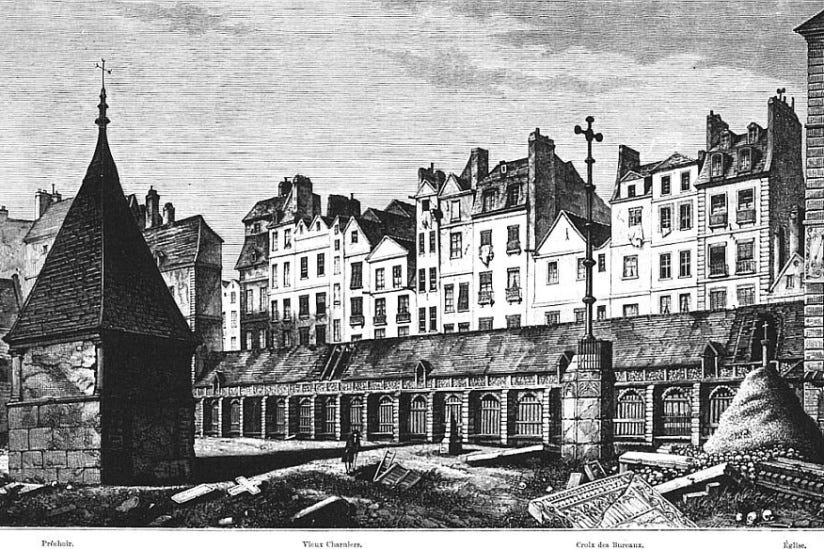

In the 12th century, the situation began to become unsustainable: in just 200 years, the population of Paris had multiplied by five. This great pressure meant that only the wealthy had access to their own graves in the overcrowded cemeteries. Mass graves became popular, especially in the most congested areas, as was the case with the Saints Innocents Cemetery, next to the old Les Halles market.

By the 18th century, the sanitary conditions in this cemetery were already unsustainable, but as it remained an important source of income for the Parisian church, the clergy continued to allow burials there. By then, the entire cemetery, like many others in the city, was surrounded by ossuaries built with the bones of the dead that were exhumed from the mass graves to bury others. Some cemeteries grew to a height of two metres, with the ground filled with human remains.

The catacombs solution

At the end of the 18th century, someone in Paris had a great idea. With an extensive network of underground galleries undergoing renovation and a health problem throughout the city due to poorly managed cemeteries, there was only one solution. After rejecting the initial idea of taking the remains to the quarries on the outskirts of Paris, Alexandre Lenoir’s option was chosen. This Parisian police general proposed using the underground tunnels to store the human remains that were overflowing from the cemeteries.

The plan was put into action by Thiroux de Crosne, Lenoir’s successor. In 1785, mass exhumations began, and the bones were transferred to the city gate known as Porte d’Enfer, in what is now Denfer-Rocherau Square. The bodies were transferred from all the city’s cemeteries to create gigantic catacombs.

The activities were carried out with a certain degree of discretion, as it was decided to carry out the transfers only at night. What was not initially considered was all the relatives who, overnight, had lost all trace of their loved ones without a place to go to pray for them. During the first two years, all efforts were focused on the Saints Innocents Cemetery, the most populated in the city, where the remains were piled up without any control to solve the prevailing problem: public health.

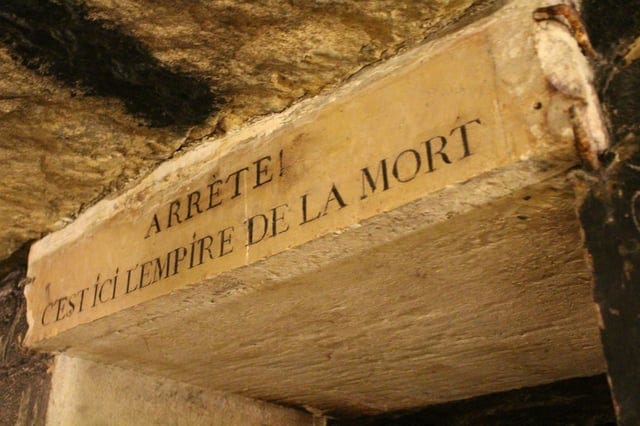

This continued until the arrival of Louis-Étienne Héricart de Thury. From 1810 onwards, this politician and mining engineer proposed renovations to the underground corridors. The idea was to transform the galleries into a mausoleum that could be visited by all those who wished to pay homage to their ancestors. In this way, the tibias and skulls began to be piled up to form more passable corridors, with references to the years of death and the parishes of origin.

During the 19th century, the Paris Catacombs were open to the public on an intermittent basis, with some historic visits such as that of the Emperor of Austria, Francis I, in 1814, or that of Napoleon III and his son in 1860. All this is known thanks to a book made available to visitors, in which they could record their experience.

Throughout the 20th century, the catacombs were also part of some of the city’s most important episodes. In World War II, after the surrender of Paris, part of these extensive galleries became the headquarters of the resistance, as the complex passageway was an unrivalled hiding place. The Germans also ended up occupying part of this underground network, which led to multiple clashes between the two sides.

In August 1944, after the liberation of Paris, free access to the catacombs was prohibited. It reopened in 1955, but from then on, only with a guide. Given the vast extent of the network, the city government has had a hard time preventing clandestine access. In the 1980s and 1990s, raves became popular, and even today you can still find videos on the Internet of people going underground to explore a world steeped in history3.

Despite the alternative, my recommendation is that if you visit Paris, you should spend some time visiting the Empire of Death. Here is the link to the official website.

I openly admit that I don’t like the Pompidou, sorry.

Montreal’s famous underground network is barely 30 kilometres long. Better built, of course, but much smaller.

Not all stories are equally beautiful. At least one girl lost her life at a party in January 2005, and her body was found two years later. So be very careful.