The Kingdom of Bamum, the best example of indigenous African cartography

A brief history of the Kingdom of Bamum, who had their own alphabet and were the creators of possibly the most iconic map of African cartography.

In the Western World, we are used to a particular idea of cartography, as unique as our cultural context. In a way, all the maps that have reached our days are built on the heritage of Ancient Greece, where Anaximander, Hecataeus, Eratosthenes or Ptolemy helped to build the concept of geography.

Beyond the Greek World, many other peoples have independently arrived at their own conception of the world. This has led them to develop a cartographic system based mainly on the knowledge, culture, and techniques existing at a particular place and time.

Unfortunately, we do not have examples of how each society constructed its way of understanding and representing its environment. Mostly because we do not even know if they did so, but in several other cases because all this production is lost. Luckily, we do have examples that allow us to digress into the great diversity.

The founding kingdom and the arrival of the Germans

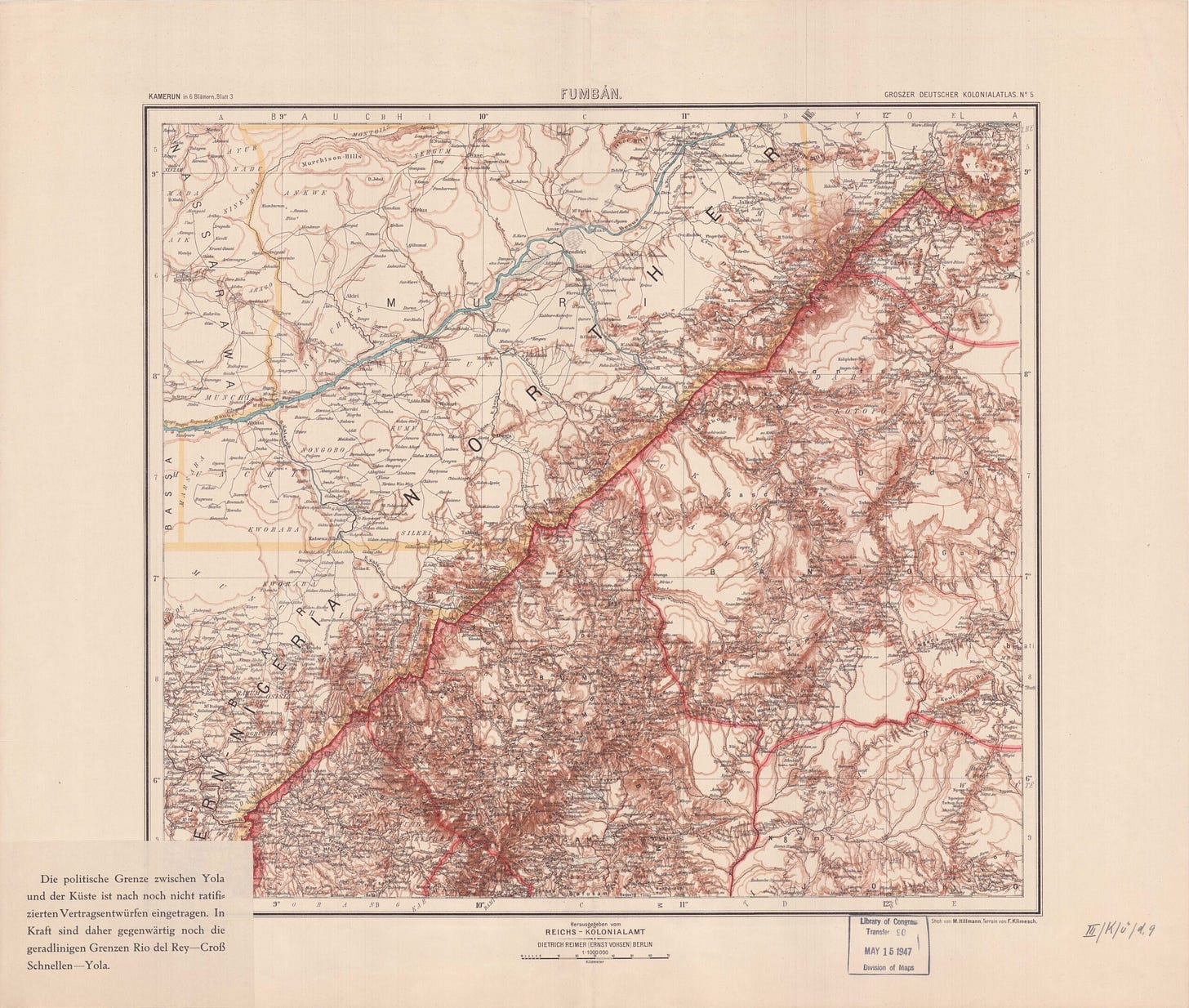

Nshare Yen was, as the story goes, a reputed conqueror of the Tikar royal dynasty who, after defeating eighteen kings and governors, decided to settle in a small region in the northwest of present-day Cameroon. There he founded the town of Fumban in 1394. As ruler, he proclaimed himself Mfon or Sultan, and chose to take over the local language and customs. Consequently, the Kingdom of Bamum was founded.

Bamum tradition lists nine successors to Mfon Nshare, who simply had the responsibility of ruling the city of Fumban, which was the full extent of the Kingdom of Bamum. It was not until the arrival of its eleventh sultan, Mfon Mbuembue, at the beginning of the 19th century, that the real splendour of the kingdom began. This sultan fortified the city, to defend it from the constant attacks of its neighbours and start fighting back. This began the expansionist period of the kingdom, with the territory expanding in four directions.

In 1884, the Kingdom of Bamum came up against European colonialism. At that time, Ibrahim Njoya1 was in charge, who opted for pragmatism and decided to collaborate proactively, accepting the protection of the German colonial forces. In a clever diplomatic strategy, Njoya sent a decorated throne to the German emperor's court, which was gratefully received. This gesture enabled the emperor to give the Kingdom of Bamum full autonomy within the German colonial empire, which allowed the sultan to stop fighting and to focus on the development of Bamum society.

An alphabet for a nation

Njoya's great concern was to preserve the cultural richness of his kingdom. He was aware that, in the face of advancing European colonialism, the oral tradition would not be able to safeguard Bamum culture. This led him to embark on a project to create a new writing system that would allow all the knowledge of his people to be put down on paper for posterity.

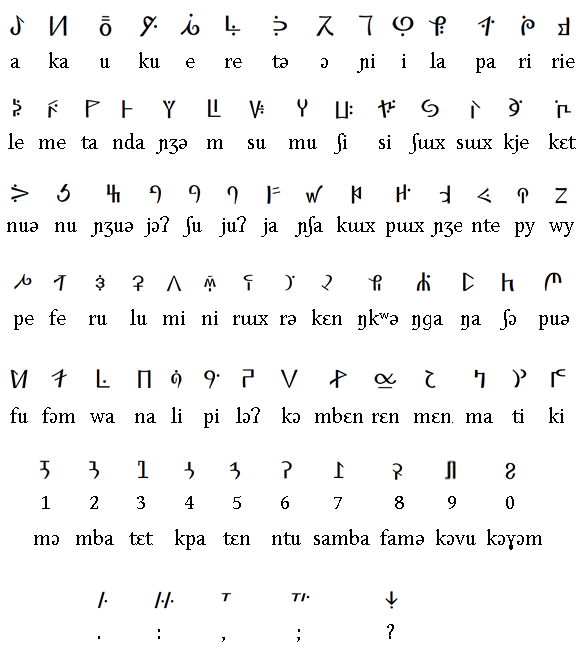

The process started from a natural starting point. According to tradition, Njoya went to his people and asked them to draw different objects. Based on the results, he began to link a symbol with each of the words of the Bamum language. This led to the creation of Lewa in 1886, a first writing system consisting of some 500 symbols and ten characters to express numbers.

In the years that followed, this system underwent several iterations in which the number of symbols was simplified, while retaining its ideographic nature. At the end of the 20th century, partly due to the Arabic influence that came when the kingdom converted to Islam in 1897, the system began to evolve into a syllabic model. It culminated in 1910 with the sixth iteration of the Bamum writing system, known as a ka u ku. This system was slightly modified in the subsequent years to simplify it by a couple of characters and make it more consistent.

Njoya’s work was completed2.

The topographical survey of the kingdom

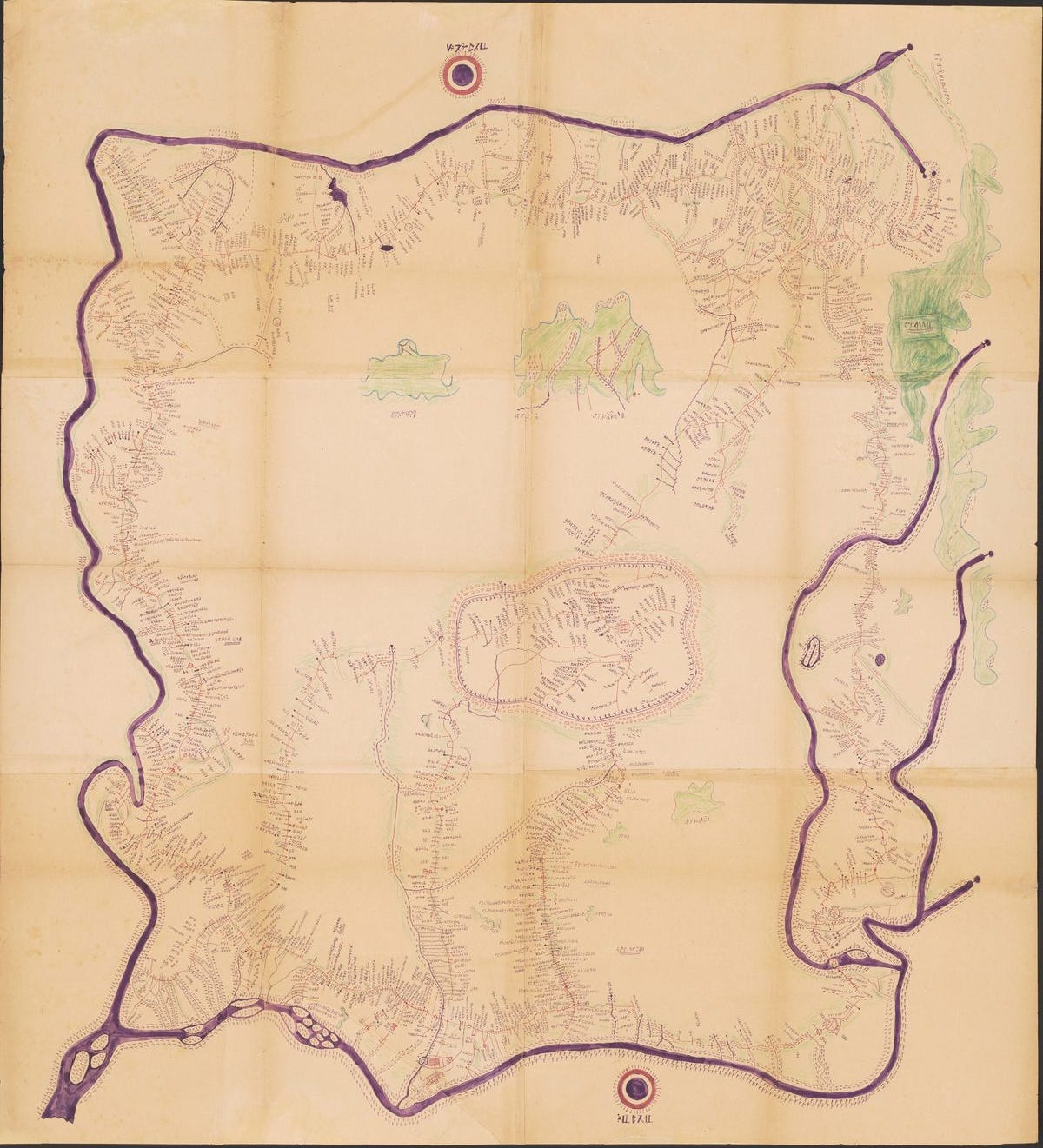

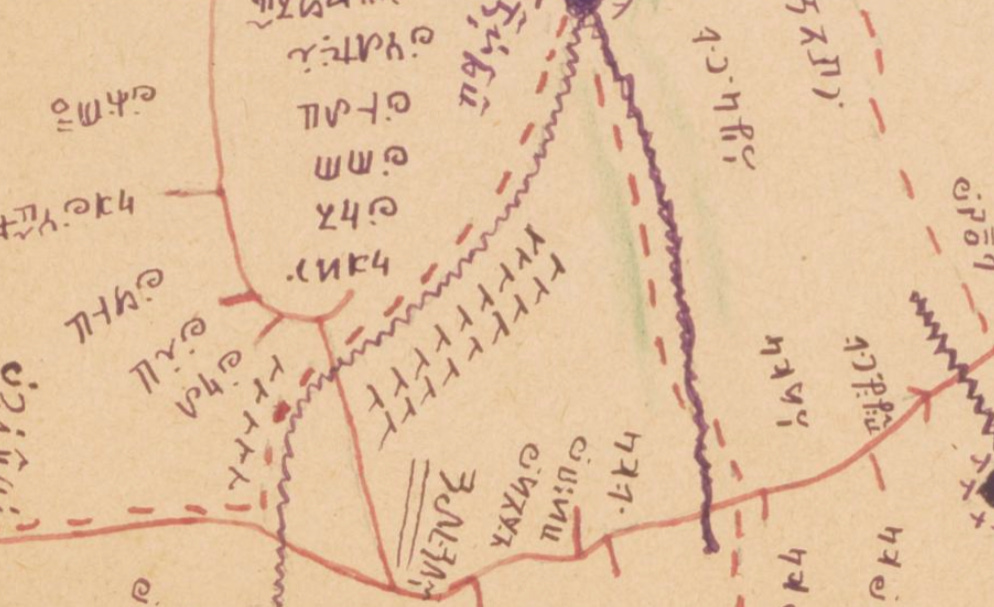

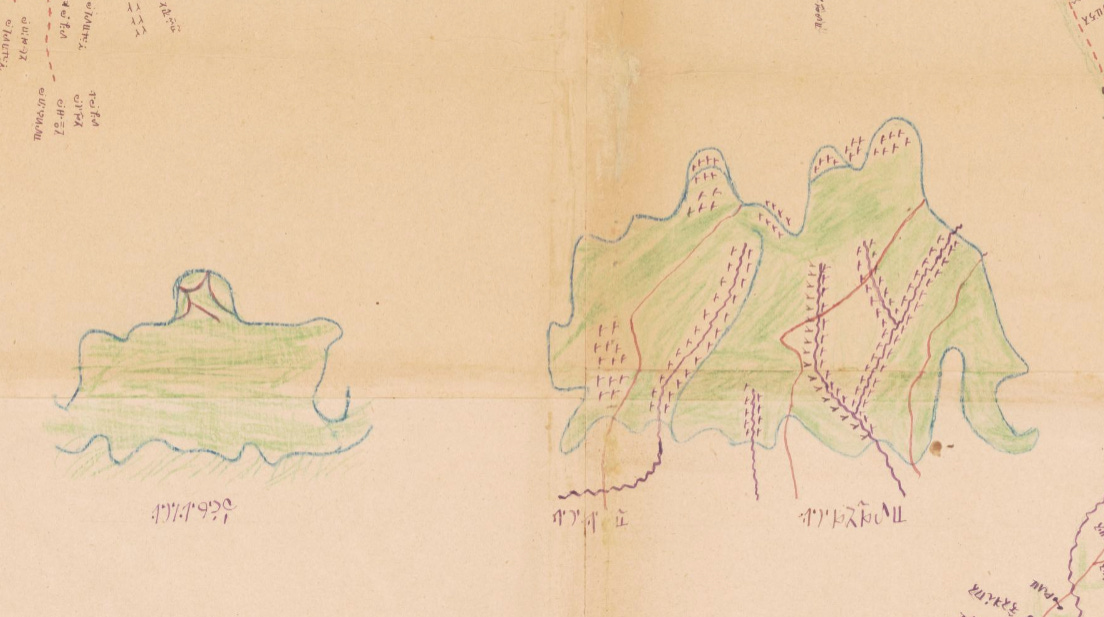

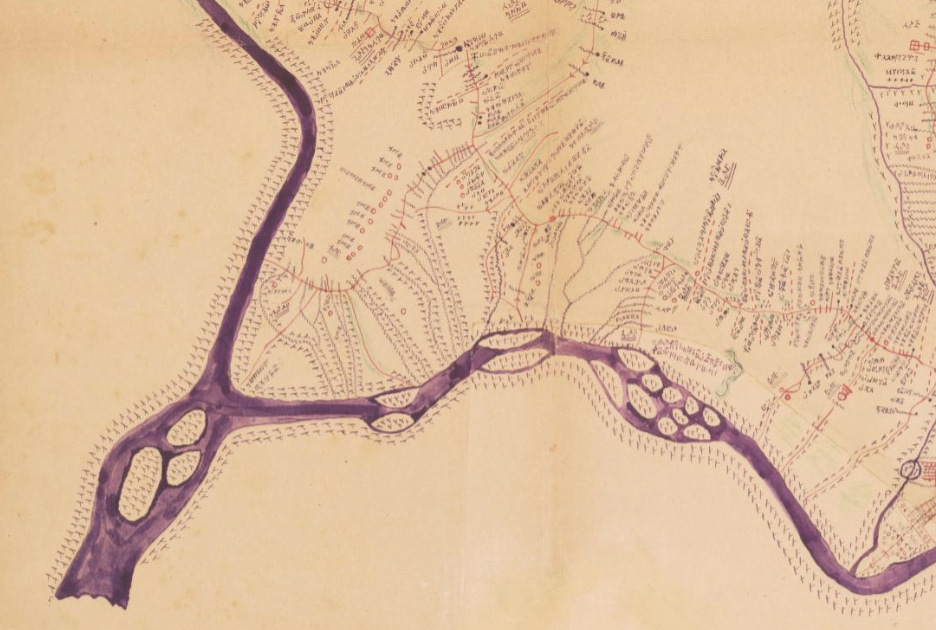

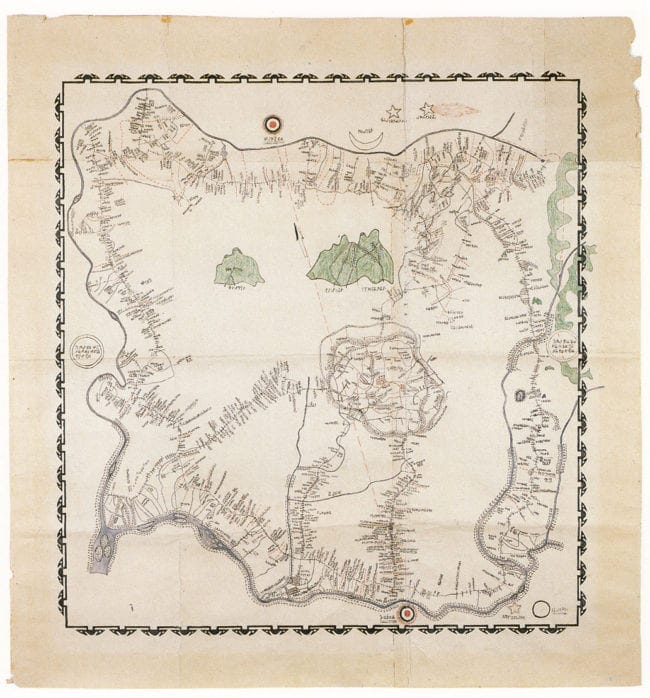

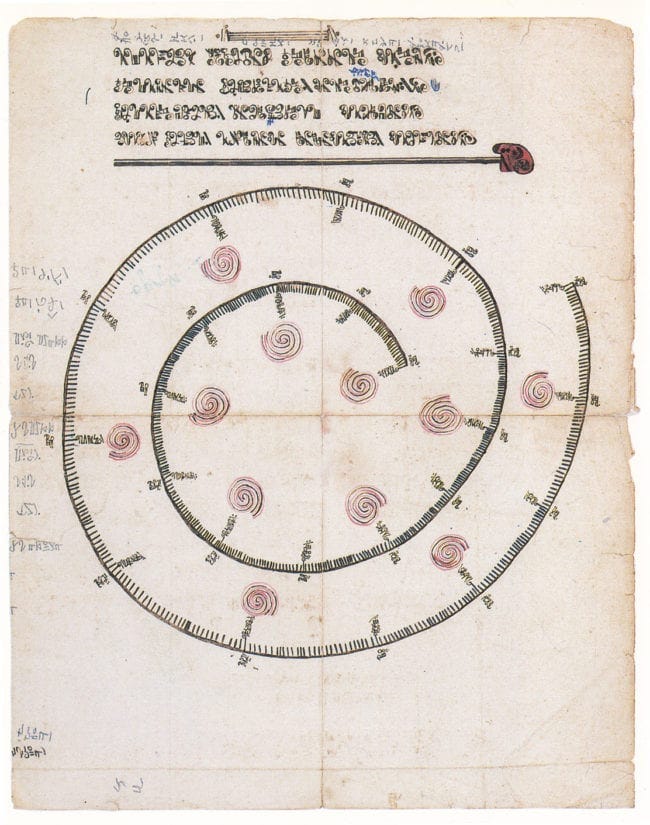

Once there was a way to capture the spoken language on paper, a world of possibilities opened up for Njoya. In 1912, he began surveying the entire Kingdom of Bamum, recruiting more than 60 people. They were organised into various groups of surveyors, accompanied by staff to clear the roads and ensure supplies, as well as a person in charge of collecting the toponymy of each of the localities. That first expedition lasted 52 days, during which time 30 stops were made and two thirds of the territory was mapped.

Later, in 1918, a new expedition collected all the data on the capital, Fumban, and a final expedition in 1920 completed the topographical survey of the kingdom. With all the information gathered, Njoya, under the guidance of his chief cartographer, Nji Mama, was finally able to publish the first map of the Kingdom of Bamum Kingdom.

As expected, the legend and toponymy used the new Bamum writing system.

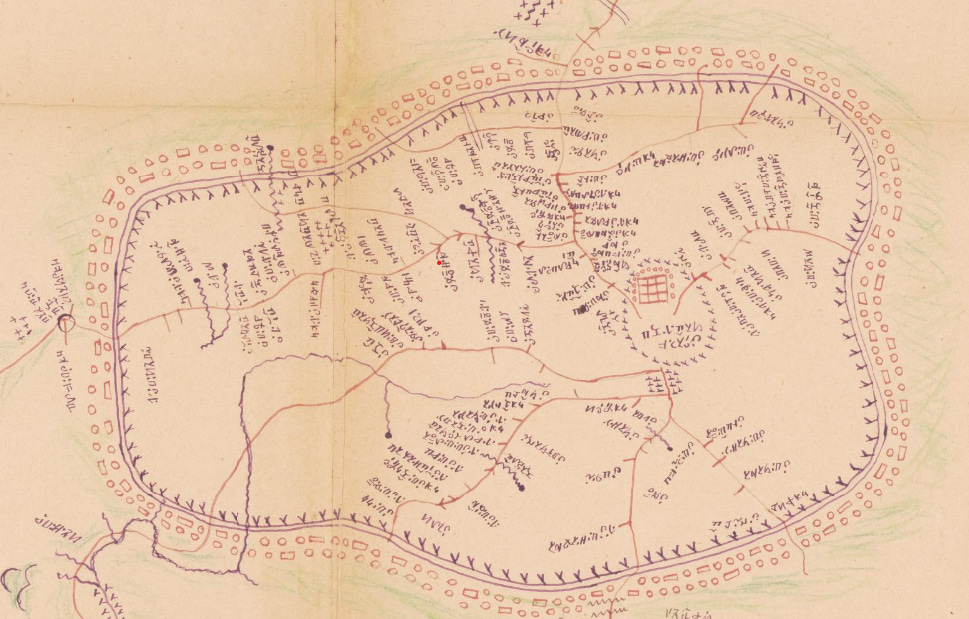

This great example of indigenous African cartography has several peculiarities. The first is that the map is oriented with west at the top, making it one of the many maps that are not oriented to the north, as we saw weeks ago. This is indicated by the sunset at the top, and the sunrise at the bottom. The central part is occupied by the oversized walled city of Fumban, which gets all the spotlight. Within it, a red three-by-three grid surrounded by dots represents the palace of Njoya.

To the east of the capital, it is possible to see the kingdom's two main mountains, Mbapit and Nkogam, which are depicted in a distinctive green colour. A tangle of purple lines, representing the rivers that served as the kingdom's borders, form the boundaries of the realm.

While the achievement of mapping the Kingdom of Bamum is astonishing, it is easy to see that this is not a scale map as such. The surveyors who covered the whole territory did not take measurements of distance as usual, but considered the time it took them to get from one place to another. This time was translated directly into distances on the map. This allowed for the portrayal of a reality that did not fit the Western definition of accurate maps, but it did meet the needs of the Bamum people. Thanks to this map, the nation finally had a full compilation of their world and their sites that could be preserved for posterity.

After the end of World War I, the German Empire lost all its colonies in Africa, and the Kingdom of Bamum, along with the rest of Cameroon, became part of the French African colonies. Njoya was soon identified as an important ally of the Germans and was exiled, and with him came the end of the Bamum people's golden age. French became the language of the elite, and the writing system was converted to the Latin alphabet to facilitate learning in schools.

Gradually, all the progress made by Njoya was wiped out.

Sultan Njoya's artist cousin

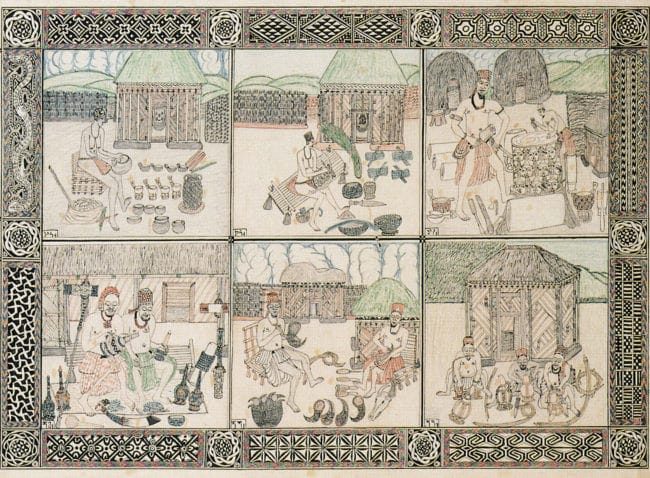

As you can imagine, Bamum culture was way more complex than their writing and their cartography. So I would like to take this opportunity and also share the work of Ibrahim Njoya, a cousin of Sultan Njoya. Ibrahim was one of the most prolific artists of the Bamum people, and was behind much of the drawings that were published in the early 20th century.

Among his work there is a copy of the map we are dealing with today, as well as multiple drawings with which Ibrahim Njoya became one of the first African artists to flirt with the cartoon and comic book format.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

It is not entirely clear who was the sultan of the kingdom at the time of the Germans' arrival. Most of the sources I have read refer to Nsangou, although some refer to Njoya. I have opted for Njoya to simplify the account, although this might not be correct.

You can read more details about Bamum script here.