The discovery and conquest of Antarctica

The south was unknown for centuries. Many cartographers imagined it, and many explorers tried to prove its existence… until Antarctica appeared.

In the middle of summer, it's a good time to think about the cold. As a good Spaniard, I complain all winter about how cold it is1, and as soon as summer arrives, I start complaining about the heat. I have been complaining for many years and have gained experience. So, keeping up with my complaints about the heat this summer, I thought it would be a good idea to elaborate on the coldest place on the planet and how we learned about its existence.

Terra Australis

It was in Ancient Greece that the world as we know it began to take shape. We know that Pythagoras already hypothesised that the Earth must be a sphere, since any deity would have the most perfect object at the centre of creation, as secondary objects showed, such as the Sun and the Moon. Two centuries later, Aristotle went even deeper into this theory and proposed that the continental masses had to be balanced, both on the north-south axis and on the east-west axis. This led him to speculate in his volume Meteorology about the existence of a land mass in the south that would maintain the balance with the known continents in the north.

This idea, with many nuances and variations, persisted until the time of Ptolemy, who described the Indian Ocean as a body of water completely surrounded by land. No original map by Ptolemy has survived, but many appeared in Europe throughout the 15th and 16th centuries that attempted to replicate the world as described by Ptolemy. One of the oldest surviving copies is this Byzantine copy from 1420.

Ptolemy's map, which was fundamental to cartography in the Modern Age, did not name the landmass in the Southern Hemisphere, nor did it conceive of a sea route between the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean. With the discoveries of European explorers during the 15th and 16th centuries, maps began to show America, and the Portuguese found out that Africa was completely surrounded by water. All this forced Terra Australis to become an independent continent, as shown in this replica of the western hemisphere of Johannes Schöner's globe from 1520.

Such was the certainty of the existence of this continent that in 1539 Charles I2 of Spain created the governorate of Terra Australis. It included the island of Tierra del Fuego and the part of Terra Australis corresponding to the Spanish Empire, according to the Treaty of Tordesillas3. The exploration of the seas continued over the following decades and centuries, but no navigator managed to reach the long-awaited southern continent. The idea gradually lost momentum, but that did not prevent some cartographers from keeping Terra Australis on their maps during the 17th and 18th centuries.

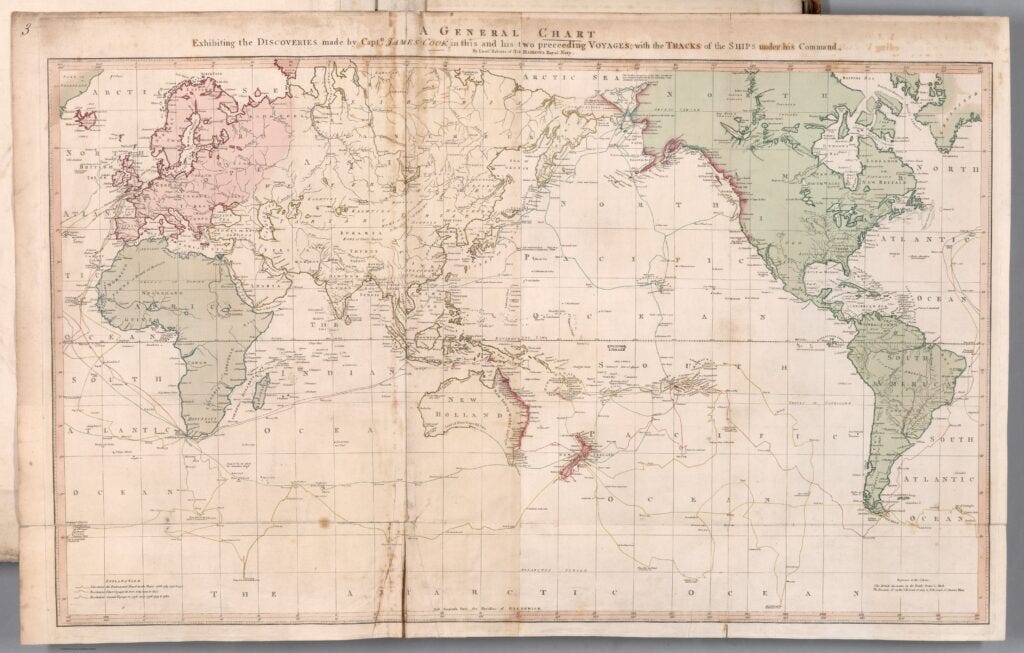

Several expeditions sought to reach this territory, but James Cook was perhaps the one who came closest. On his first voyage, he circumnavigated the New Zealand archipelago to prove that they were islands and not part of a larger continent. On his second voyage, he became the first explorer to sail south of the Antarctic Circle on January 17, 1773. A year later, he traveled five degrees further south, although he did not manage to find Terra Australis either.

The discovery of Antarctica

James Cook's map of his voyages no longer showed any continents in the south and only referred to the Antarctic Ocean, but it turned out to be wrong. The land described by the ancient Greeks, based on their cosmology and worldview, was indeed there after all.

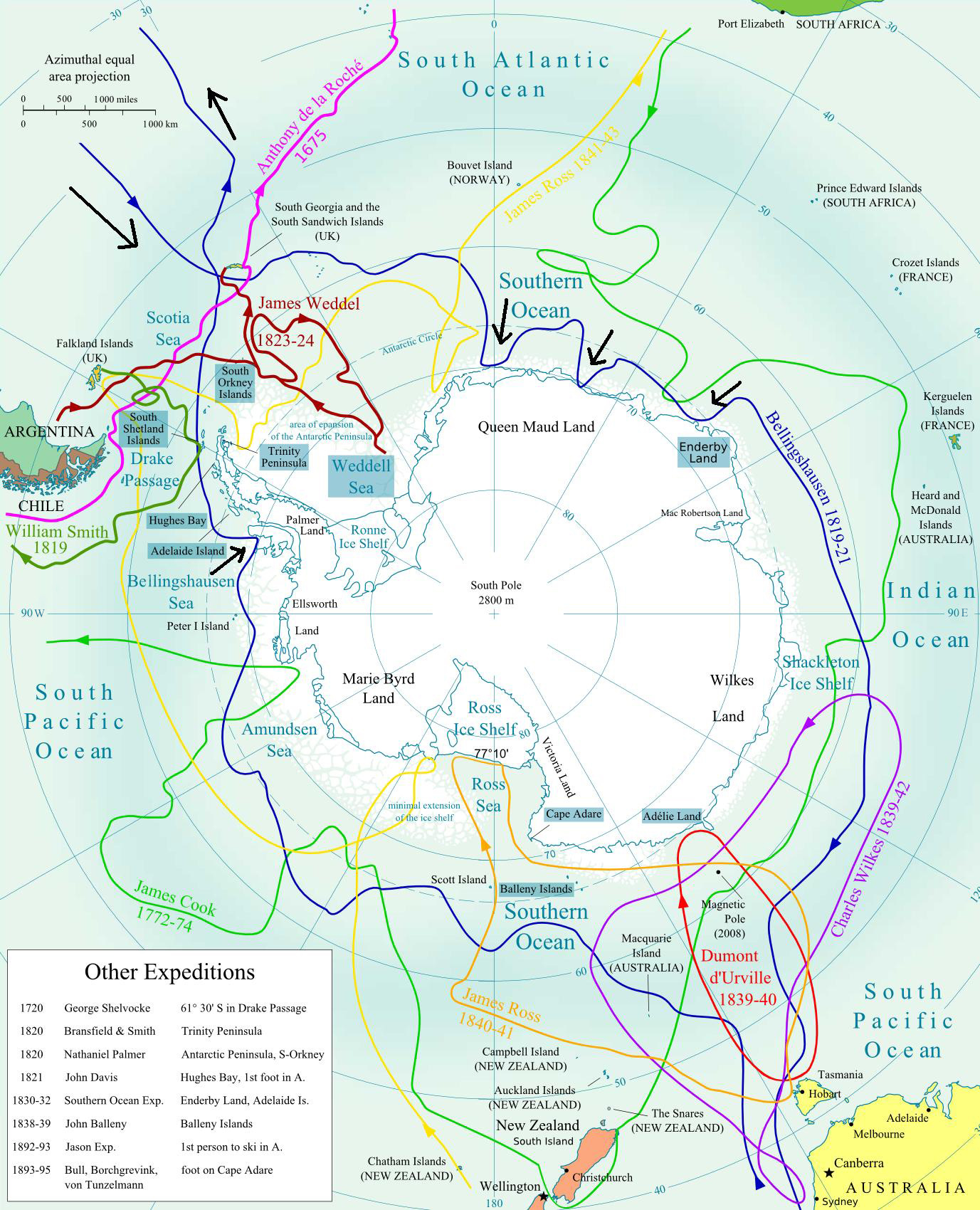

There is some controversy over who was actually the first explorer to sight Antarctica. For years, it was believed that it was the British explorer Edward Bransfield on January 30, 1820, but everything points to the Russian Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen having sighted the ice floe on January 27 of that same year. At that time, the American Nathaniel Palmer was also sailing the same seas, so he may have been the first. In any case, the year 1820 marks the moment when Antarctica finally returned to the maps as a continent in its own right.

During the rest of the 19th century, many other navigators explored the coasts of the new continent. Reaching the coast of Antarctica was difficult, and the constant presence of icebergs did not facilitate navigation along the coast to collect data. Additionally, the various explorers came from different countries or companies, so the exchange of information was not frequent. All this meant that it took more than six decades to gain a reasonably reliable understanding of the shape and actual extent of the new continent.

In 1886, one of the first maps of Antarctica was published in The Scottish Geographical Magazine, entitled Supposed outline of (the) Antarctic Continent. Subsequently, many other cartographers ventured to draw this new continent, even without scientific information to validate its shape, but with some certainty about its location and extent. A good example is this representation of the South Pole by British cartographer John Bartholomew, from 1893.

Exploration and the journey to the South Pole

On January 24, 1895, a small boat led by Norwegian Henrik Johan Bull docked on the coast of Cape Adare in Antarctica, and its six crew members successfully disembarked. John Davies had already claimed to have landed in Antarctica in 1821, although there is no reliable evidence of this. Several historians argue that it is unlikely that no other explorer had set foot on land in 75 years, but none of the possibilities have been verified, unlike the case of Henrik Bull. Interestingly, this expedition was financed by a Norwegian tycoon who was looking to find the right whale, which was the main objective of the mission. The fact that many crew members set foot on Antarctica for the first time was nothing more than a happy accident, as Bob Ross would say.

Between the end of the 19th century and, mainly, in the first decade of the 20th century, many explorers attempted to venture into the new continent. But one undoubtedly stood out from the rest: Ernest Shackleton. During the Nimrod expedition, which lasted from 1907 to 1909, Shackleton and his companions crossed the Ross Ice Shelf, climbed Mount Erebus, reached the South Magnetic Pole and the Antarctic Plateau. He left only one milestone unachieved: he failed to reach the South Pole by just 180 kilometres.

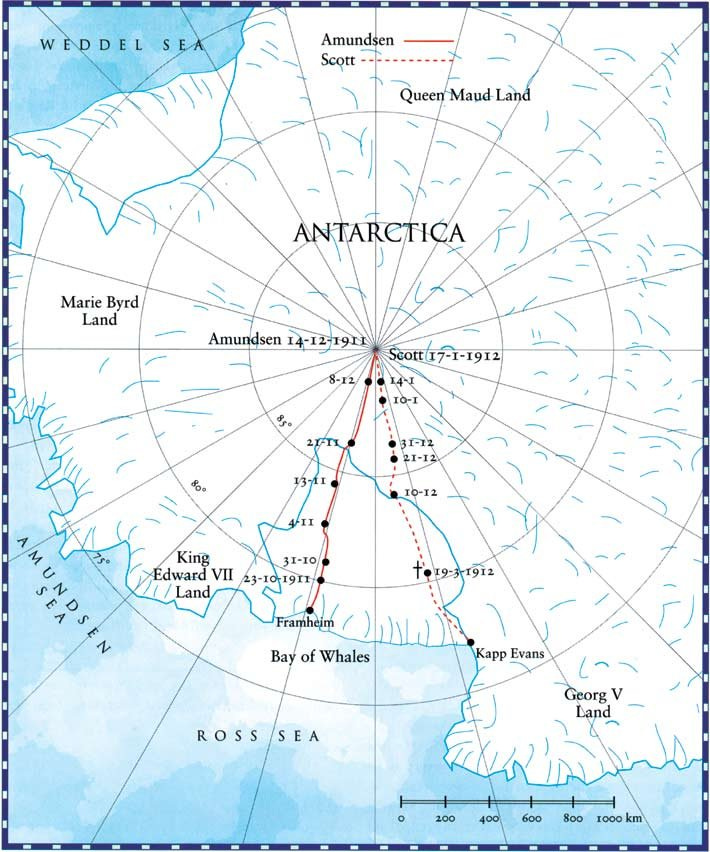

Between 1909 and 1910, two explorers began preparing to be the first to reach the South Pole. On one side was the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, who had already achieved fame by becoming the first explorer to sail the Northwest Passage, reaching the Pacific Ocean from the Atlantic Ocean via the coast of Canada. On the other hand, there was the Englishman Robert Falcon Scott, who had been part of an initial expedition with Shackleton to Antarctica between 1901 and 1904. During this time, he had learned a lot about the conditions on the cold southern continent.

In 1911, both explorers set up their bases on the Ross Ice Shelf. Amundsen did so near the Bay of Whales, while Scott did so on the opposite side, near the McMurdo Sound. This was a significant handicap for Scott from the outset, as his base was 100 kilometres further away than Amundsen's. This proved decisive in Amundsen becoming the first man to reach the South Pole on December 14, 1911, 34 days before Scott.

The saddest part of this story is that Scott and his expedition did not make it back to base and lost their lives in the attempt. His body and those of his companions were found in November 1912 in a tent more than 700 kilometres from the South Pole. The diary found next to him confirmed that, although late, he had also achieved his goal of conquering the South Pole.

In Segovia, my hometown, the temperature consistently drops below 0 degrees in the winter time. Despite living in Spain, I am on the northern slope of the mountains and at an altitude of 1,000 metres. Not Moscow or Chicago cold, but cold nevertheless.

Charles V, by its Holy Roman Emperor title.

The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in 1494, divided the world into two parts so that there would be no conflicts between Portuguese and Spanish explorers.