Six years of COVID

This December marks six years since COVID first appeared somewhere in China.

This year, viruses are loving me. In the last six or seven weeks, I’ve been ill three times, which I suspect have been caused by three different viruses. The first one attacked my digestive system directly, not being able to eat properly for almost a full week. The second one had the classic symptoms of a cold or mild flu, with a spike in fever one day and some discomfort for a few more days.

But the third one, which decided to visit me last Saturday, is undoubtedly the most troublesome of all. It hasn’t stopped me from working, cooking or tidying the house, but it has given me an annoying, deep cough that has ruined my sleep for almost seven consecutive nights1. Not every year, but sporadically, I do catch a cold with a cough that lasts a couple of days, but I don’t remember ever having this annoying symptom for so long.

Some people have asked me what exactly I had, but to be honest, I didn’t get tested to find out which three viruses were involved. As these are common symptoms and are more or less bearable with the usual remedies, knowing the specific virus was not going to make the slightest difference2. Despite this, the other day, while talking to a woman at the gym, she told me that this nasty cough is usually caused by the version of COVID that is currently circulating in Spain.

It was not until this moment that I realised that I have no memory of ever having had COVID. I have had what I consider regular colds a few times in the last years, but apart from the second virus this season, none of them have given me a fever. Some of them may have been COVID. Maybe not. At this point, with vaccines and six years of exposure, it’s impossible to know how the antibodies in my bloodstream got there.

And I insist, I don’t really care.

All this has led me to think that it has been a shocking six years since the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the cause of COVID, was initially detected. It passed from a bat3 to an animal that was taken to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China. Here, this virus came into contact with humans4.

That same January, news began to arrive from China. On 21 January, The Guardian was already reporting that 139 people had been infected with a virus similar to SARS. SARS had killed more than 700 people between 2002 and 2004, mainly in China, and its high mortality rate had already set off alarm bells. The Chinese government did not hesitate for a moment, placing Wuhan under quarantine on 23 January. A week later, seeing that the virus had already spread to the rest of the country, it also imposed strict measures on face masks and transport.

From Spain, and from half the world, we followed the news as if it had nothing to do with us. Geographical and cultural distance, sadly, tends to limit people empathy. But as more cases were detected in other countries, we began to feel the danger more closely. Before the end of January, 26 countries had already detected cases of COVID, covering every continent in the world except Africa5.

By March, the risk had become clear. In the West, the proportionality of the measures taken by China had been questioned, but until that March it was impossible for similar measures to be taken in any country. Everything seemed unthinkable until Italy was forced to take action in the face of the imminent collapse of its healthcare system. On 8 March, the Italian government declared a lockdown of the whole of northern Italy, extending it to the whole country the day after.

The world needed a democratic country to accept the urgency of the situation, and that country was Italy. It may have been one of the countries under the most pressure from the new pandemic, but it was certainly not the only one that had been needing to implement similar measures for days or weeks. Italy’s first step allowed 23 other countries to also implement drastic measures over the following week in order to control infections. Then, one of the strangest periods in recent human history began.

Overnight, billions of us were confined to our homes, our attention almost entirely focused on the spread of the new pandemic. At first, we wanted to convince ourselves that it would only last a couple of weeks, but then two more weeks were needed, and then two more. Before we knew it, almost three months had passed in which the only thing that had happened in the world and in our daily lives was the pandemic.

Many people became obsessed with the data, publishing tables with the latest infections and deaths. They were on the news, in the newspapers, on the radio and even on social media. There were some authoritative bodies, but multiple individuals had their own way of curating the data and presenting the information. Many people who had no training in epidemiology or data processing also took it upon themselves to publish data on a daily basis6.

Everywhere you looked, there were tables and graphs. The data became like that annoying neighbour you can’t seem to shake off at the front door. They stuck to you and came back every day with a small update that made you feel informed, but more likely kept you obsessed. Obsessed under a sense of transparency, creating more pressure and fear than just being a good information tool.

The world moved on in different ways in different countries. There were more lockdowns and the use of masks continued to be recommended or mandatory for a couple more years, but little by little we returned to normal. Looking back, I remember that in April 2020 I didn’t think it would be possible to completely recover the world that had existed before COVID, but it seems that six years later not so much has changed.

For a while, many people managed to work from home, although most were gradually called back to the office7. You see more face masks on the street, and people are somewhat more aware of the importance of not unnecessarily spreading viruses to those around them, but healthcare systems continue to be close to collapse every winter.

And perhaps worst of all, we are still not prepared for another pandemic. Yes, we have significant technological advances that we did not have before the COVID pandemic, and some prevention systems have improved in several countries. But the situation remains fragile if we are looking for mechanisms for prediction, early detection and rapid response. Denialism has only increased in the past five years, and global geopolitical fragility only serves to fragment us and prevent us from establishing joint and global measures to keep us alert.

All this has little to do with what I had in mind when I started writing. I had many maps in reserve to elaborate on COVID after all these years, but as I wrote, I began to remember and felt a twinge when I thought about the ridiculous level of information overload we were exposed to.

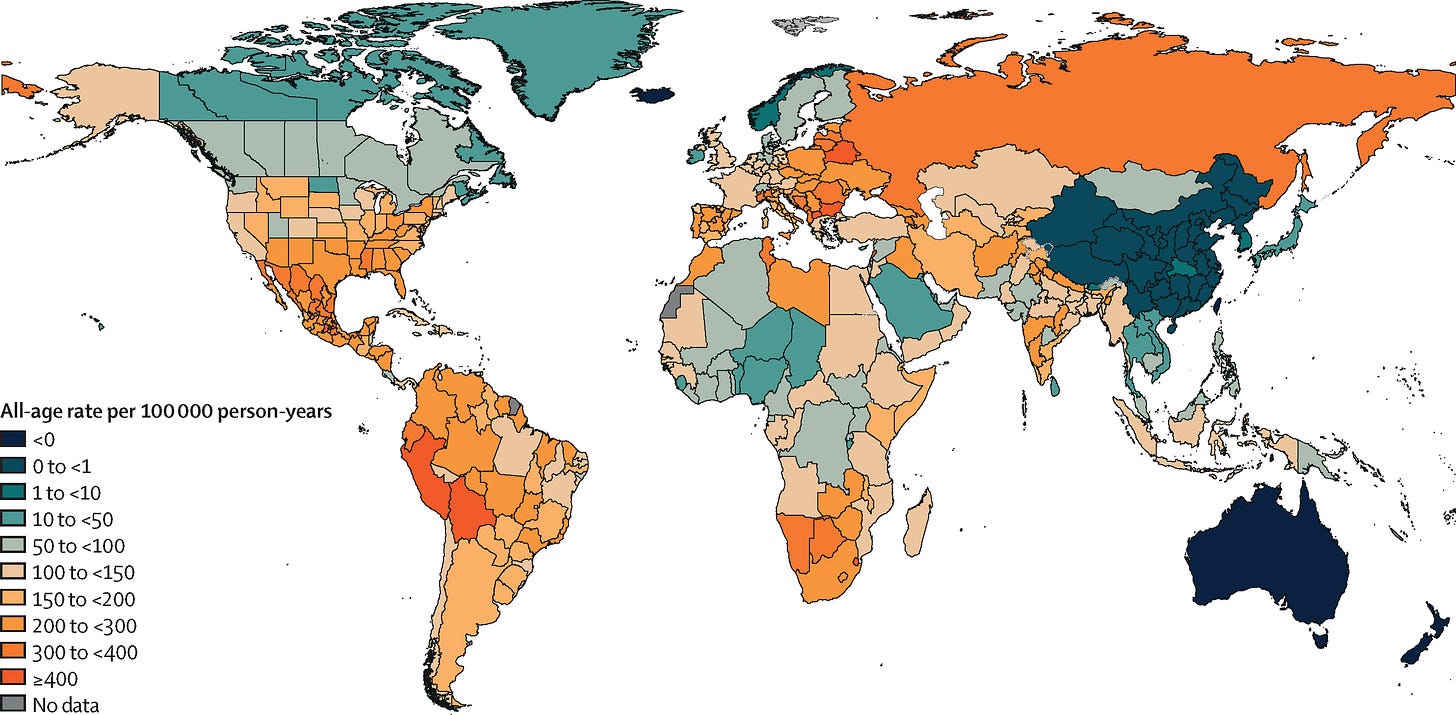

That is why I have chosen not to share all those maps and to stick with a brief review of what it was like. That said, there is one map I do want to share because I think it is important to put everything we went through into context.

In the first two years, nearly 6 million deaths were reported worldwide, but this study by The Lancet shows how they increased during this same period to 18 million people. In just two years, 0.25% of the world’s population died, which is truly outrageous. The majority died because of the virus, but many also died because of the collapse of healthcare systems and the questionable practices that were carried out in many countries.

It is very difficult to limit the impact of a new virus, but it is much easier to have healthcare systems in place so that they do not collapse if we find ourselves in this situation ever again.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

I still have a cough. The nights are becoming more bearable, since I no longer cough continuously throughout the night, but I often spend a good deal of time awake trying to stop my life from escaping through my throat. I’m Spanish, I love a good exaggeration.

And I’m not someone who finds peace of mind in naming symptoms.

Over the last six years, there have been multiple investigations, and in general, they point to the origin of this virus being in the rhinolophus affinis. It is a species of bat from Southeast Asia that, among other things, is known for being one of the transmitters of most types of coronavirus.

This is what most research points to, but there is no complete scientific consensus. And it may never be, due to a lack of evidence, as the Chinese authorities did not carry out (or share) any analysis of the animals sold at the Huanan market after it was closed and fumigated on 1 January 2020.

Detecting the first cases was very difficult, so the data is limited by the screening and testing capabilities of different countries. It is reasonable to assume that many more than 26 countries already had cases, including some African countries.

Many even gained a certain amount of fame and prestige during these months thanks to these practices.

Not because productivity was poor, but for various reasons, such as bosses being unable to measure the value of their workers if they did not see them warming their chairs.

Nicely said. I hope your health improves. Feliz Navidad!