A history of relations between Iran and the West

From the Great Game to multiple coups. How the ambitions of the West and Russia repeatedly put Iran's sovereignty in check.

Before I begin what I will tell you today, I would like to write a disclaimer so that this text is not interpreted in words that I have not written down. Everything I am about to tell you does not seek, in any way, to justify anyone's behaviour. What it does seek to do is to provide a historical context that can help to understand how some things are the way they are today. Of course, there are many details that I will have to gloss over, as Iran's history is at least as complicated as that of any other country in the world you can imagine.

With that in mind, let us begin.

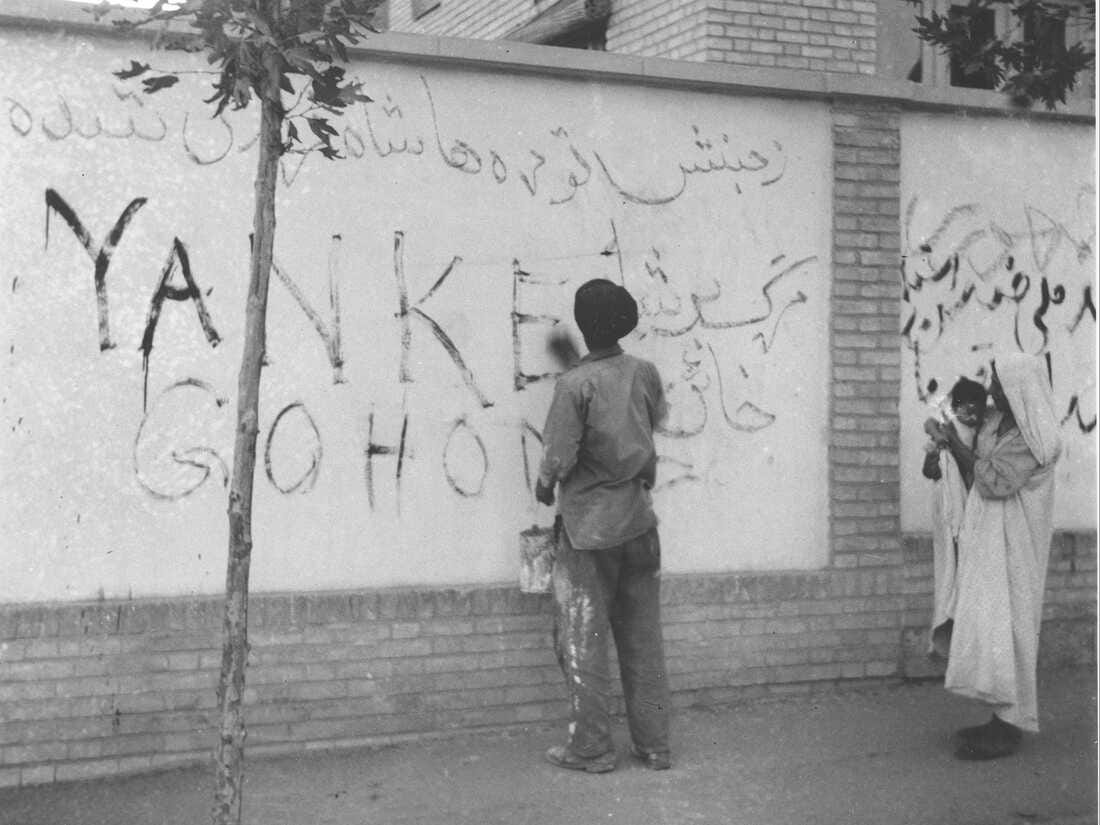

The anti-American sentiment in Iran and, in part, also a strong anti-Western sentiment, is well known. That sentiment, though commonly claimed to be a consequence of the Islamic Revolution, predates it by a long way. Before 1979, the United Kingdom and Russia were the primary actors in the ongoing Western interference in Iran.

This story is a journey through Iran's history, with a special focus on the many times the West challenged Iran's autonomy to decide its future.

Iran and its 2,500-year history

Some of the most powerful and long-lasting empires in the Middle East, Asia, and even Europe have ruled over the area where Iran1 is today. Perhaps the most memorable are the Achaemenid Empire (550 BC-330 BC) and the Sasanian Empire (224-651), but a certain continuity was maintained with many other less recognised empires, such as the Seljuk Empire (1037-1194), the Persian Ilkhanate (1256-1335) and the Timurid Empire (1370-1507).

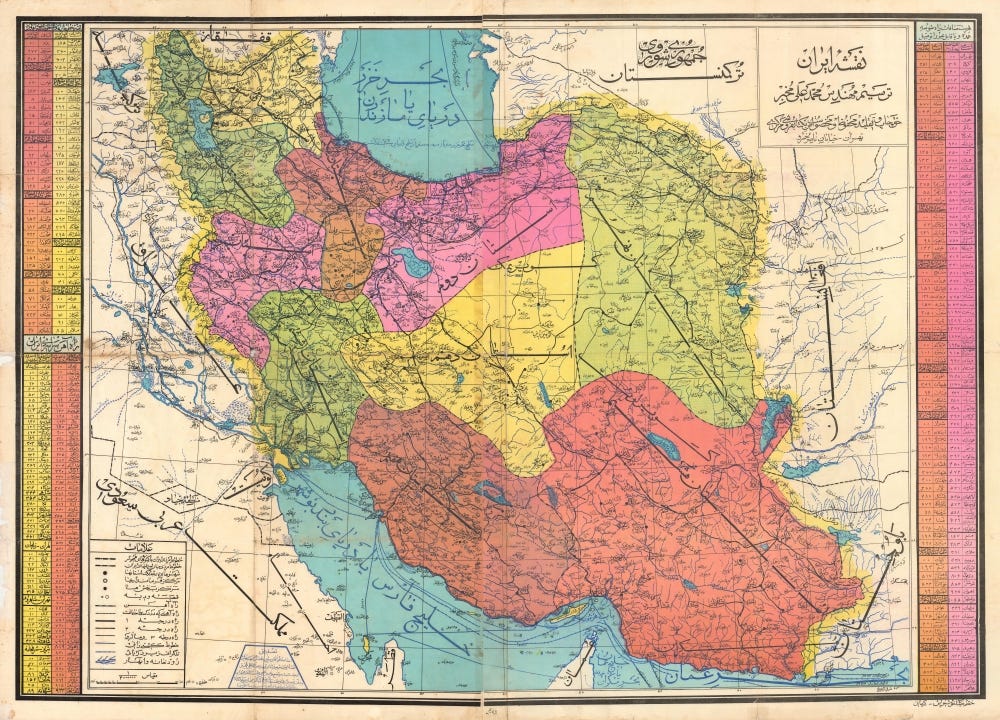

For more than two millennia, the territory of present-day Iran was part of a great regional power, which has somehow established a cultural consistency throughout history that is quite rare in the world2. Since 1501, when the Safavid Iran was established, the country's territorial boundaries have remained fairly constant, which has helped greatly to persist that sense of nationality and belonging.

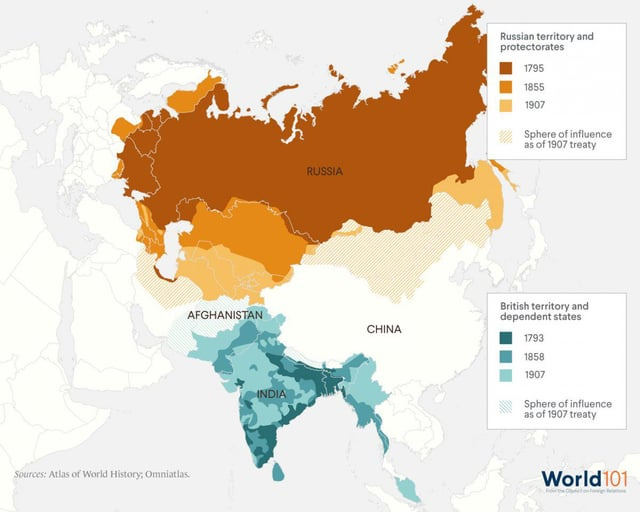

While Iran is one of the few countries not colonised by European powers, it has been subject to European influence and interference for several periods. Despite having earlier contacts with the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British, we can mark the beginning with the Great Game between the Russian Empire and the British Empire for control of Central Asia. As part of this rivalry, the colonisation of Asia advanced and, where colonisation could not reach, areas of influence were established.

This was the case for Iran.

The Qajar dynasty used Russian and British interests in Iran as a source of money throughout the 19th century. The Russian Empire, much better placed, took it upon itself to modernise the Iranian army, and brought in Russian nationals to train doctors, officers, and teachers for the Shah's court. The British Empire did challenge the Russian Empire in the industrialisation of Iran, playing a key role in the creation of factories, the railway network, and the telegraph network. It’s clear that the Russian and British collaboration with the Shah was far from altruistic; the main objective all along was to fight for influence and, in the process, to make considerable profits for their companies.

The Iranian people did not accept that the Shah negotiated with foreign forces in pursuit of his own wealth, with no real benefit for the population. This sparked a series of protests in 1905 that eventually transformed the authoritarian Iranian monarchy into a constitutional monarchy. The zones of influence signed by the Russians and British remained in place, but their power over the Shah almost disappeared completely.

The 1921 coup and the end of the Qajar dynasty

The early 20th century saw the discovery of large oil reserves in the Middle East and, as a result, the interest in the region increased dramatically. World War I was the perfect excuse for the Ottoman Empire to invade Iran from the west with the support of Germany3. Russia and the British Empire, on their part, did not fight the Ottoman invasion directly, but also sought to control the country from their side. None of the belligerents cared in the least that the Qajar dynasty had declared Iran neutral in the conflict. They all wanted to control those oil reserves and guarantee that they would have the rights to exploit them.

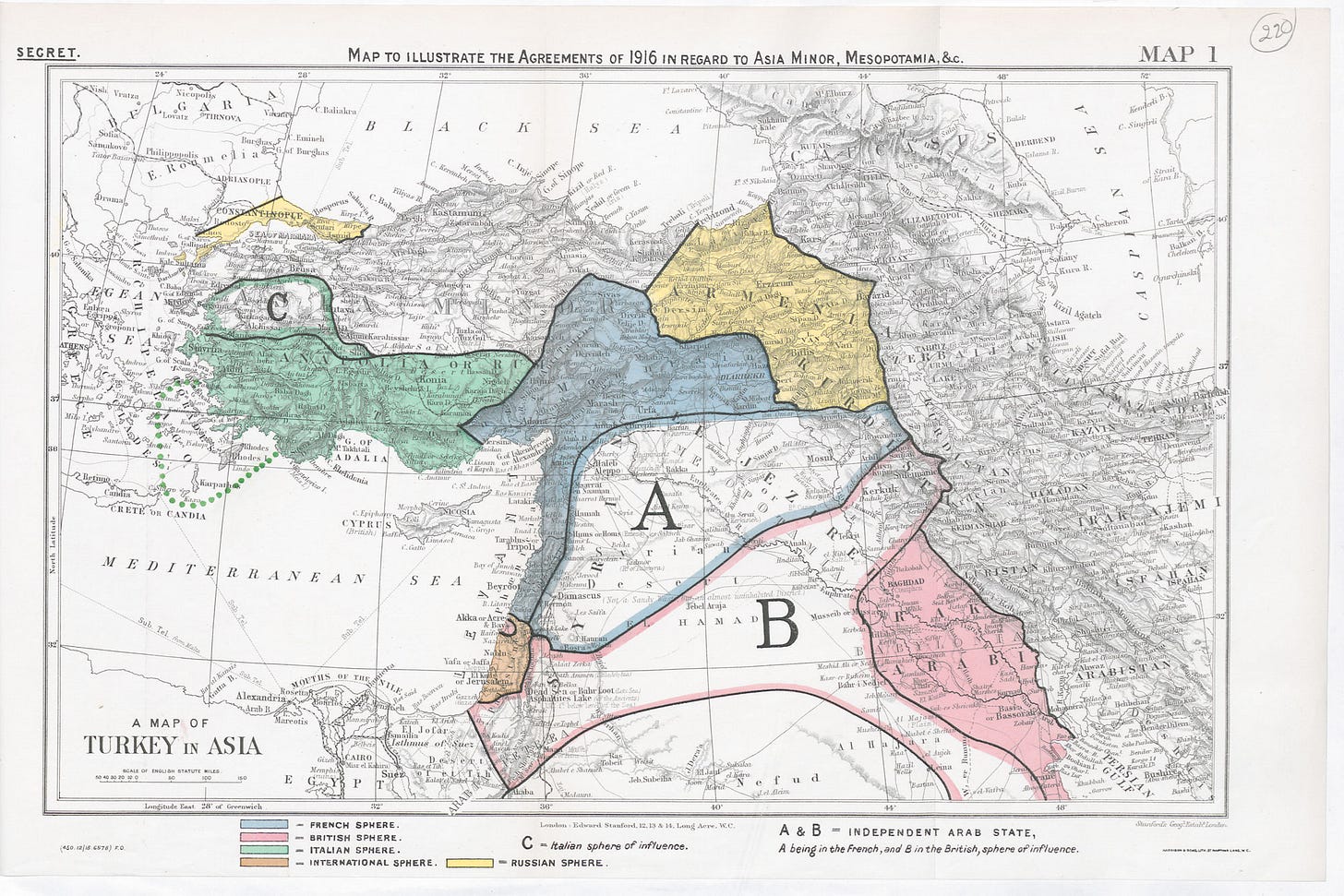

At the end of World War I, Russia was busy with its revolution, and the Ottoman Empire saw its integrity threatened by the partition proposed by the Allies. Since the British Empire was the only nation to successfully invade Iran, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was granted complete authority to take advantage of Iran's oil reserves.

As can be seen in the map above, the partition of the Ottoman Empire under the 1916 agreements gave the British Empire full control of the territory west of Iran. Coupled with the fact that it already controlled all the territory to the east and the southern coast of the Persian Gulf, it is not surprising that the British were not content with exploiting the oil reserves. They also sought to turn the country into a protectorate.

But the British Empire spent a lot of money during World War I, so it could not engage in another military campaign for complete control of Iran. So it opted for a cheaper option. British General Edmund Ironside provided strategic intelligence for a coup to depose the Qajar dynasty and establish a stronger government. Reza Khan led the revolt in 1921, placing Seyyed Zia as prime minister. The initial idea was to reform the Qajar monarchy, but after several years of struggling to put down all the internal revolts and separatist movements, in 1925 Reza Khan proclaimed himself Reza Shah, the first Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty.

World War II and the Anglo-Soviet Invasion

The British Empire's plans did not go according to plan. Reza Shah kept the agreements with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, but politically he began to act independently and in his own interests. He signed trade agreements with numerous countries, including the Soviet Union, although he remained wary of the Soviets' expansionist past. Stability allowed the Shah to lay the foundations of a strong state, with the creation of a central bank and investment in industry, infrastructure, and education.

With the arrival of the 1930s, the Shah began to get closer to Nazi Germany, captivated by its military strength and the progress of its industry. This led to the signing of important partnership agreements in 1936, with hundreds of Germans arriving in Iran to help improve the country in all areas. This agreement allowed Iranians to be considered pure Aryans and, as such, were totally excluded from the Nuremberg Laws4.

World War II broke out in 1939 and, once again, Iran declared itself neutral in the conflict. This did not prevent the British Empire from once again looking out for its own interests. If Nazi Germany had succeeded in bringing Iran closer, what was to prevent Iran from eventually breaking the oil exploitation agreement still held by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company?

In 1941, after Germany attacked the Soviet Union, fear across the Allies intensified. Iranian oil production was essential to the Allies, and it could fall into German hands. This led to pressure from the UK and the Soviet Union for Iran to expel all German citizens and sever all relations with Nazi Germany. Not only did this provoke direct rejection by Reza Shah, but Iranian citizens also organised protests against British and Russian interference. After all, it was not the first time that European powers had tried to decide for the Iranian people.

On 25 August 1941, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union began an invasion of Iran to take control. The Shah sought explanations from the British and Soviet embassies, but they failed to provide him with any possible agreement that could stop the invasion. Reza Shah also sent a telegram to Franklin D. Roosevelt asking for protection from the unlawful invasion by the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom. The only response he got from the US president was a distant appeal for cooperation with the Allies.

In just 23 days, the invading troops reached Tehran. Reza Shah was exiled to South Africa and his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was put in charge.

The new prime minister, Mohammad Ali Foroughi, chose to play along with the Allies and broke off relations with Germany, Italy, Hungary and Romania, as well as handing over all German citizens in Iran to the British and Soviet armies. In 1943, Iran eventually declared war on Germany. The occupation continued until the end of the war, which only increased the Iranian public's distrust of the British and Russians.

The 1953 coup

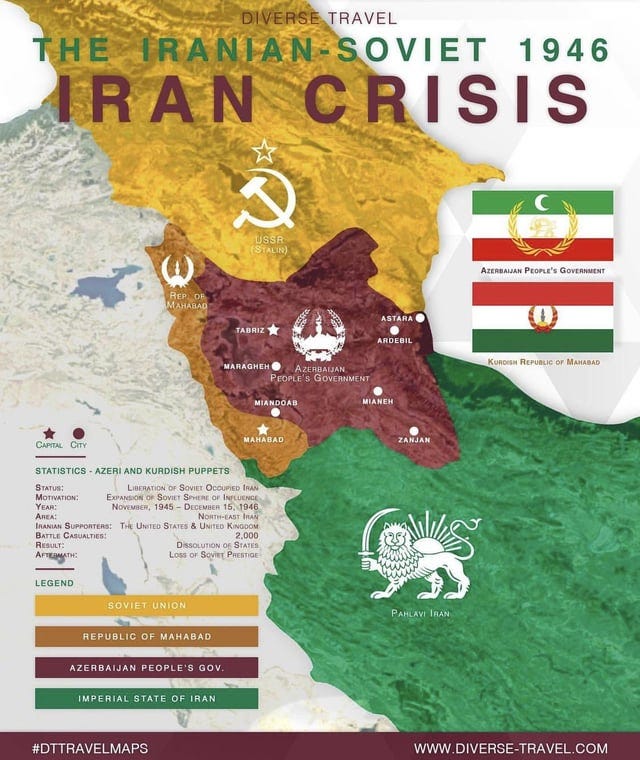

The end of World War II should have marked the end of the Soviet and British occupation. Both countries were given six months to withdraw, which the UK fulfilled, but the Soviet Union did not. Instead, Joseph Stalin decided to support the separatist movements in the northwest: he supported the independence of the Azerbaijan People's Republic and the Republic of Kurdistan5.

Finally, the Soviet army left Iran in 1946 and, a few months later, both independence movements were suppressed.

The end of the invasion did not end the Iranian people's dissatisfaction with their treatment by the West. This gradually led to protests against the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and how it remained a vestige of Western imperialist interests in the region.

Reforms began in 1949, when the Shah sought a change in the existing constitution to give greater power to the monarchy. Both the US and the UK advised the Shah not to go down this path and to keep the state operating as it already did, but he ignored them. The reform also had enemies within the country, which led to an assassination attempt on the Shah, that was linked to Islamic fundamentalism and the Tudeh, the largest communist party. This allowed the Shah to get rid of part of the opposition, but a new enemy was soon to emerge.

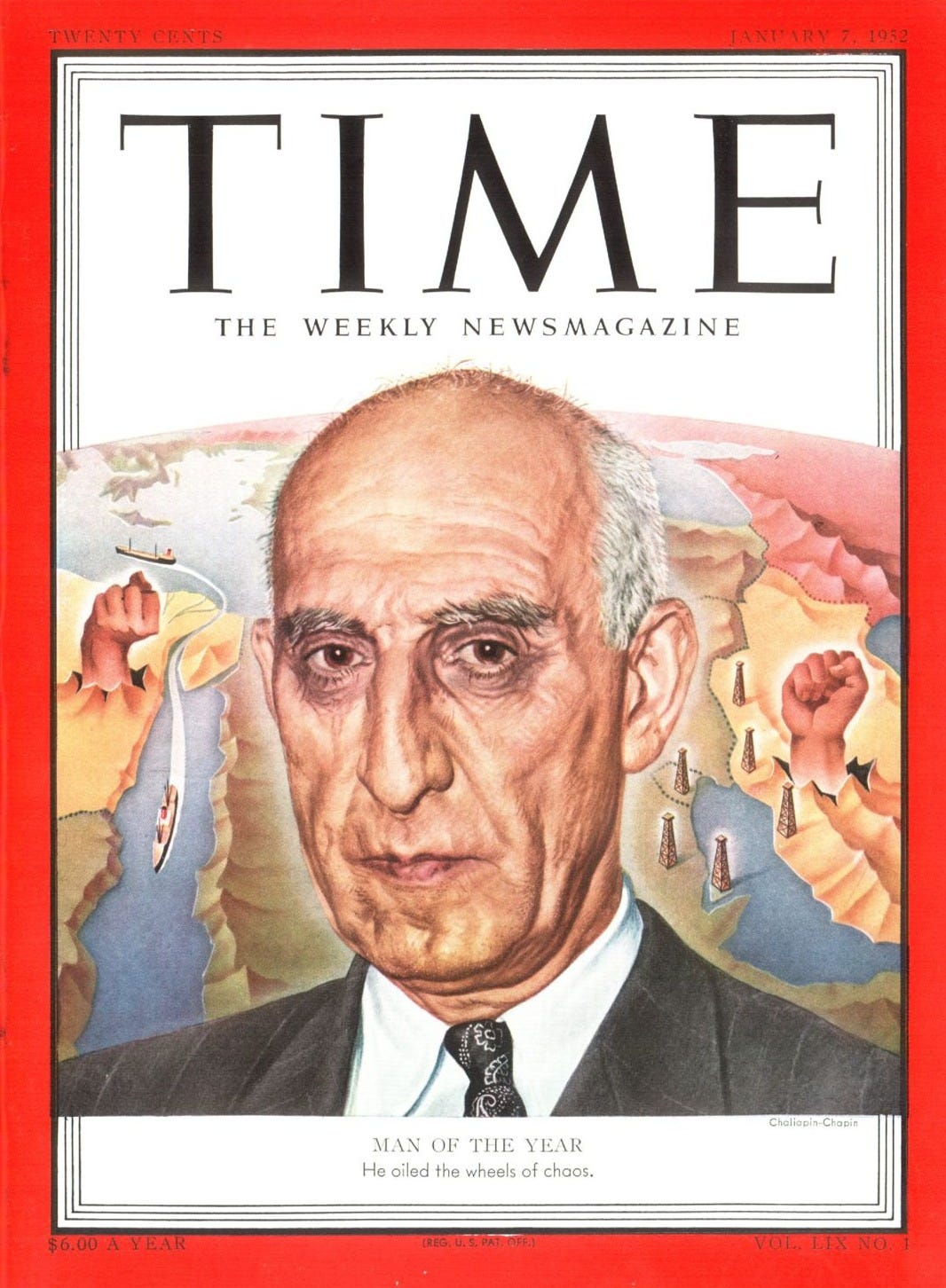

Mohammad Mosaddegh was elected prime minister in 1951, partly because of his outspoken opposition to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's authoritarian reforms. But his popularity reached its peak when, among his first measures, he chose to nationalise the country's oil companies, including the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. Attempts were made by Mosaddegh to negotiate an agreed exit, only to be met with total opposition from the British oil company and the UK government.

This was a major setback for US and British interests in the region. The US tried to negotiate directly with the Shah, but he initially objected, as he was unwilling to go against public opinion. Oil nationalization was overwhelmingly supported by the Iranian populace, and it was impossible to oppose.

With little choice, the UK imposed an embargo on Iranian oil, thereby shocking the Iranian economy and cultivating the initial discontent needed for the next phases of the plan. The next step was known as Operation Ajax, a covert operation by the US CIA and Britain's MI6 to overthrow Mosaddegh. Propaganda and bribes were used to curry favour with Iranian politicians, religious leaders and members of the Iranian military. Finally, it culminated in the return to power of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi with a new authoritarian regime in 1953.

The US and the UK achieved their goals. They had a Western-aligned ruler in power, but undoubtedly underestimated the long-term consequences. Iranian society had been expressing frustration for decades about foreign interference and how its leaders did not fight for the interests of the Iranian nation. All this discontent continued to grow and was joined by internal friction with the religious establishment, which together led to the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

But that is a story for another day.

PS: I wanted to include the Iraq-Iran war (1980 - 1988) here as well, since it also adds to the pile of foreign interference Iran has suffered in its history. But for it to make sense, I needed to elaborate on the Islamic Revolution, which would have overextended today's article.

If you liked this, I can keep the story going with another article about the Islamic Revolution and the subsequent war with Iraq.

Tell me about it!

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

Persia was the name used in the West to refer to the country until 1935, but within the country the name Iran (in its Farsi version) has been used since around the year 1000. That is why I will mainly use the name Iran, without going into other connotations. For example, there are quite a few authors who refer to Persia as the country before the Islamic Revolution of 1980, and after the revolution, they talk about Iran. This, as such, has no basis beyond an intention to differentiate the country with the regime change, which is not substantiated by any internal change of name.

In Europe, depending on the limits we set, some examples can be found. Outside Europe, perhaps the only examples that can be considered are Japan, China (or part of China) and Ethiopia.

This was not the first time the Ottoman Empire had tried this. It had done so before in 1906, taking advantage of internal Iranian revolts.

Adolf Hitler himself declared the entire Iranian people part of the Aryan race.

Also known as the Republic of Mahabad.

As always, the longer historical view helps make sense of the present. Thanks for sharing this overview. I'd definitely like to read the follow-up on the Islamic Revolution and Iran-Iraq war.

https://open.substack.com/pub/mdavis19881/p/the-increased-nuclear-threat-after?r=19b2o&utm_medium=ios