Islarios: collections of islands

A journey through some of the first islarios, published between the 15th and 16th centuries.

Islario is a word that does not exist in English, or at least does not have such a simple translation. According to the Royal Spanish Academy1, islarios are books that include a description of the islands of a geographical area and books that represent maps of all the islands of a geographical area. Although dictionaries often lean on the side of simplicity, in this case I think they summarise perfectly the essence of the word. An islario is a compilation of islands limited to a geographical area, although in some cases that geographical area is so large that it encompasses the entire planet.

In the widest sense, the first island collection we encounter is also the reference work on geography of the ancient world: Geographia, written by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century. Clearly, it is not an island collection per se, but rather a book that describes and depicts in detail the known world, including lands, seas, and islands. Among these islands, at least 53 have names, and all of them correspond to the world known to Ptolemy: the Mediterranean Sea and Europe.

To find a universal and encyclopaedic island compendium, we have to go back to the 15th century. De insulis et earum proprietatibus2 was a book published by Domenico Silvestri in 1406 in which the author attempts to compile all the known information about the islands of the world. The documentation work is impressive, as it effectively brings together all the islands that appear in classical documents and various medieval treatises. It also includes the new islands that were being discovered as Europe began to learn about the rest of the world.

Silvestri’s book does not include any maps and focuses purely on encyclopaedic information. The islands are listed in alphabetical order and each one is accompanied by a description, which varies in length depending on the island’s relevance and in quality depending on the information available. It is undoubtedly a work of its time, with all its prejudices and ignorance:

Zanzibar is a large island in India covering sixteen thousand stadia. Its inhabitants, both men and women, are repulsive, very thick and corpulent, four times stronger than other men; if they were as tall as their thickness would require, they would look like giants, both in appearance and strength. They devour five times more food than others, have large, pointed mouths and ears, a horrible look in their eyes, and upturned noses that rise towards their foreheads. The women are equally deformed and their hands are four times thicker; they are all black and walk around naked, covering their private parts, and their hair is so tangled and curly that it is almost impossible to untangle it with water. They feed on meat, milk, rice and dates, and quench their thirst with a concoction made from spices.

The first Italian illustrated islarios

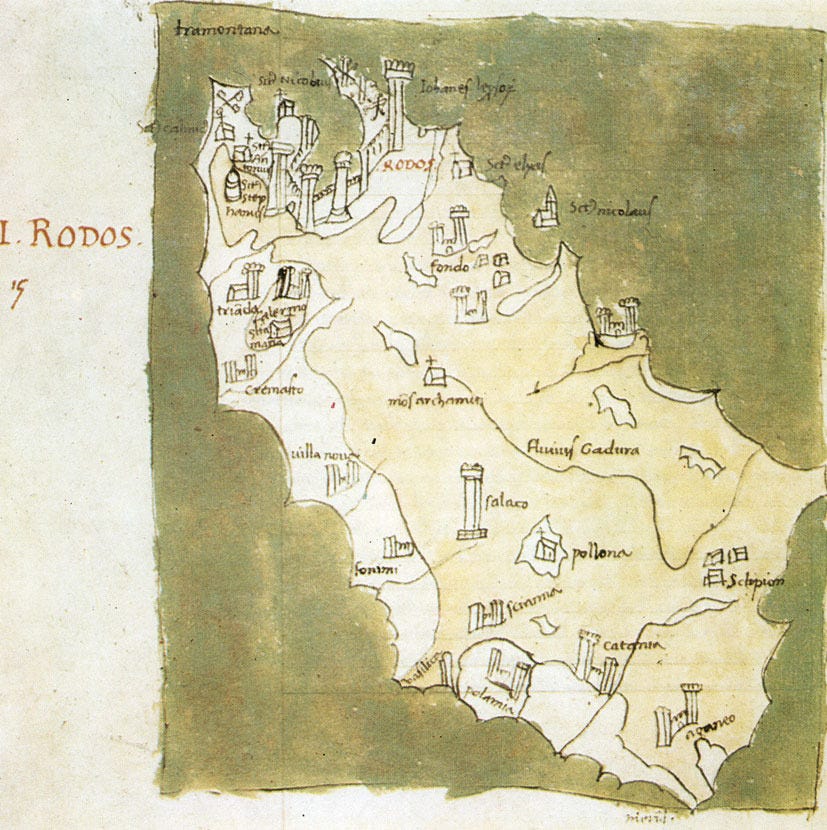

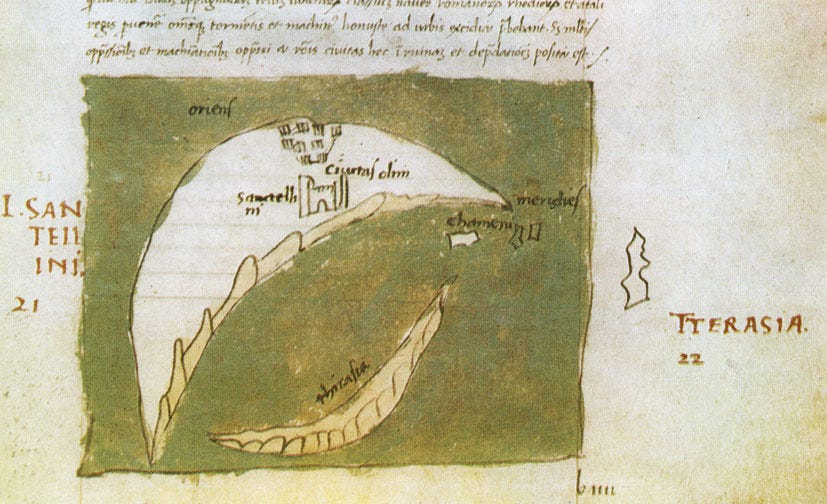

It was not only the Italians who published islarios, but they were the ones who explored this peculiar format in greater depth. Just 14 years after Domenico Silvestri wrote his detailed encyclopaedic work, Cristoforo Buondelmonti published Liber insularum Archipelagi3. In this atlas, Buondelmonti put all his knowledge of the Aegean Sea on paper. Unlike Silvestri’s work, this one did contain maps. More specifically, 79 maps covering all the Greek islands that the author had documented.

Buondelmonti’s graphic work was limited to a small geographical region, which made sense. With very few previous works detailing the cartography of the world, focusing on a single known region allowed him to spend the necessary time compiling all the available information. This produced a work that would be useful for navigation and future cartographers.

In 1485, the Venetian Bartolomeo dalli Sonetti used Buondelmonti’s work as a reference to create a new island atlas, L’Isolario, with cartography that was more faithful to reality so that it could be used by sailors and navigators. All of Sonetti’s maps included a compass rose to facilitate orientation and also detailed the islets near the coasts, as well as areas with shallow waters where ships could run aground.

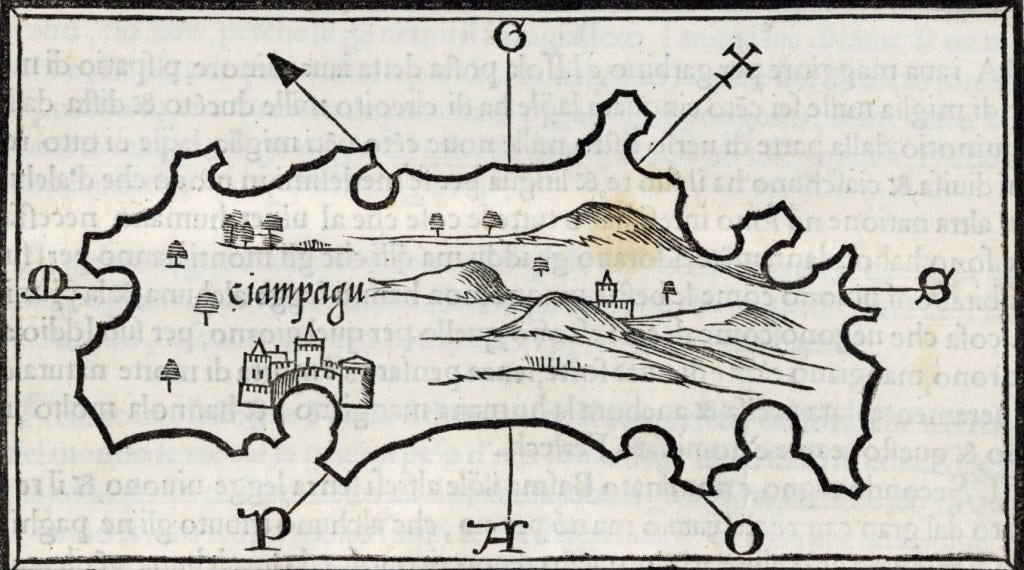

In the 16th century, with the arrival of Europeans in the New World, island atlases began to expand their horizons beyond the Mediterranean Sea. An example of this is the Isolario published by Benedetto Bordone in 1528. Its more than 100 maps show almost all the known islands of the Mediterranean Sea, but also many of the newly explored territories. It includes the main islands of the Caribbean, such as Cuba, but also an exceptional curiosity: the first map of Japan drawn by a European.

El Islario General

To conclude this brief overview of the history of island atlases, I will focus on what I consider to be the most important one of the 16th century: El islario general de todas las islas del mundo4, written and drawn by Alonso de Santa Cruz between 1539 and 1560. As its name suggests, Santa Cruz’s intention in this work was to cartographically describe all the islands of the world, according to the information available to a person from Seville in the mid-16th century. Unlike the authors we have seen previously, this author had access to all the discoveries made by Spanish and Portuguese explorers, which added value to his work that was lacking in the works of the Italians who preceded him.

The maps in this atlas, 1115 in total, are grouped into four regions: the North Atlantic, the Mediterranean and adjacent areas, Africa and the Indian Ocean, and the New World. Unlike Sonetti’s atlas, in which aesthetics played a major role, Santa Cruz’s work is highly functional. All the maps are accompanied by details of latitude and longitude so that they can be located in the world, as well as a scale that allows the actual size of the islands described to be known.

In total, 209 islands are described and named. It may come as a surprise, but given that almost 500 years have passed since this work was published, many of these islands no longer exist. Or at least they do not exist as islands, as none of them have sunk below sea level. An example can be seen above, where Cadiz and Sancti Petri appeared as islands, even though today they are connected to the rest of the Iberian Peninsula.

Something similar occurs with the islands of the Nile River, with which Santa Cruz referred to a group of islands located at the mouth of the African river. Today, these islands have become part of the great river delta. If we look at the map in detail, we can see how sediments were already piling up, as shown by the dotted area representing surface waters that are not navigable.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

This is an Academy based in Spain with the purpose of ensuring the stability of Spanish language. As you may imagine, not everyone agrees with their approach.

It can be translated as On Islands and Their Properties. There are copies in Spanish, but I haven’t been able to find one in English.

It can be translated as The General Island Atlas of All the Islands in the World. Here you can explore a copy.

As a curious fact, El Islario General by Santa Cruz and the Isolario by Bordone contain the same number of maps: 111. They do not overlap in content, but it is still an interesting fact.

Is it possible also that a lot of continental locations were thought to be islands early in their discovery because no one had been able to sail all the way around them yet, and island was the default assumption?