How many continents are there in the world?

It depends. It depends on whether you choose the historical and cultural perspective or the scientific perspective. And in both cases, there is a great deal of inconsistency.

Before reading further, you must answer this survey. Do not worry, neither I nor anyone else will be able to see your answers. Today we are going to have some fun.

For those of you who are impatient, so you don’t have to wait until the end, I’ll give you the answer now: it depends. I know that’s not the precise and satisfactory answer that people usually expect these days, but it’s the only answer that can be given in short.

The long answer is that there are many ways to approach the question, as well as a set of reasons behind the one you have chosen. There is no wrong answer, but it is interesting to understand the history behind the idea of a continent and why there are discrepancies.

The continents of the Old World

For the Greeks, the Aegean Sea was the centre of the world. On either side were the known lands of Europe and Asia. To the north, the two lands were separated by the Dardanelles Strait and the Black Sea; to the south, by the great Mediterranean Sea1. This clear division led the ancient Greeks to call these two lands continents, which simply meant contiguous lands2.

It was only a matter of time before the Greeks began to debate whether Libya, the name they used to refer to North Africa, should be called a continent or not. In the 6th century BC, Hecataeus of Miletus reproduced the map of the world as Anaximander had described it shortly before3. It already described the three continents, with the classic separation between Europe and Asia, and using the Nile River to separate Asia from Libya.

In ancient times, there were many other ways of understanding the world. The Babylonians believed that their capital was at the centre of the world, surrounded by a series of regions with their own characteristics, until they reached a great ocean on the outer edge4. Ancient Chinese texts speak of a world divided into nine continents or regions, which corresponded to the different territories and islands of their known world.

The Greek idea of three continents might have been just one of many that went down in history, were it not for Ptolemy. Ptolemy was responsible for one of the most influential books of Ancient Greece, Geographia, which, in addition to all the knowledge it managed to preserve, also established a very particular idea of the world that solidified throughout the Middle Ages.

Before Columbus left Spain for his first trip across the Atlantic Ocean, Europeans had reached a consensus that the world was divided into three continents. Europe was divided from Asia by the Dardanelles Strait, the Black Sea and the Don River; Africa was divided from Asia by the Isthmus of Suez. Columbus managed to reach land, which he believed to be the eastern coast of Asia. As more explorers took the new route, it became increasingly obvious that they were facing a new set of contiguous lands, a New World.

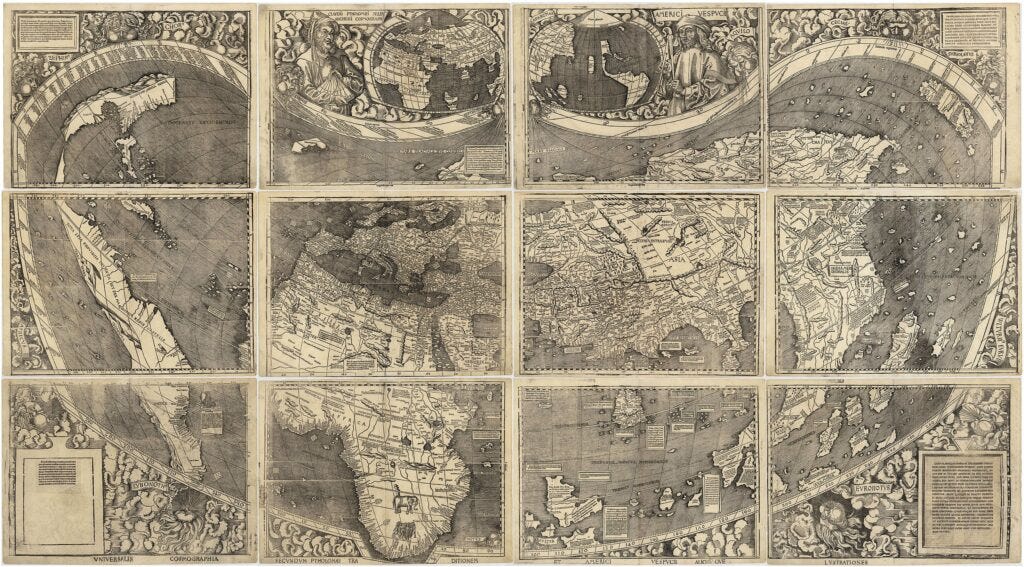

In 1507, Martin Waldseemüller was the first to publish a world map showing the Americas separated from Asia and with an ocean on its west coast. Previously, some maps had appeared showing the coasts of America, but it was not clear that there was an ocean separating it from Asia. On this map, the Americas appear as an independent continent. Well, actually two, as Waldseemüller shows North America and South America as completely separate.

The continents in the Contemporary Age

After shaping America, European explorers also discovered Australia in 1606, although for more than a century it was considered part of Asia. During the 18th century, some geographers began to raise the possibility that Australia was not a massive island, but a continent in its own right, something that became the accepted view from the 19th century onwards. In that same century, the Russian Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen discovered the coasts of Antarctica5, although it was not considered a continent in the conventional sense until the mid-20th century.

This last detail is key. Surely, some of you thought when you started reading this article that the world is divided into five continents, as shown by the five rings symbolising the Olympic Games.

However, this viewpoint is not entirely accurate.

This flag was designed in 1913. The most popular theory is that each of the rings symbolises each of the inhabited continents: Europe (blue), Africa (black), America (red), Asia (yellow) and Oceania (green). Apart from the obvious somewhat racist symbolism, it appears that this was not Pierre de Coubertin’s reason for the design. This is what its author stated at the 1914 Paris Congress, when its use as the Olympic flag was approved:

Five equal, interlocking rings coloured blue, yellow, black, green, and red stand out against a white background. Moreover, these six colours can be combined to represent all national colours, without exception: Sweden's blue and yellow; Greece's blue and white; the tricolours of France, Great Britain, America, Germany, Belgium, Italy, and Hungary. Spain's yellow and red stand alongside newer nations like Brazil and Australia, as well as ancient Japan and young China. Here is a truly international emblem.

Coubertin’s idea was to create a flag that would, in some way, bring together all the flags of the world so that any country could feel represented in some way.

It is true that the Olympic Charter accepted for some time the idea that the five rings represented the five continents, but this was dismissed in 1951 because it was inconsistent with the original meaning of the symbol. Since then, the Olympic Committee has insisted that the idea is erroneous and that it should not be promoted as if it were true.

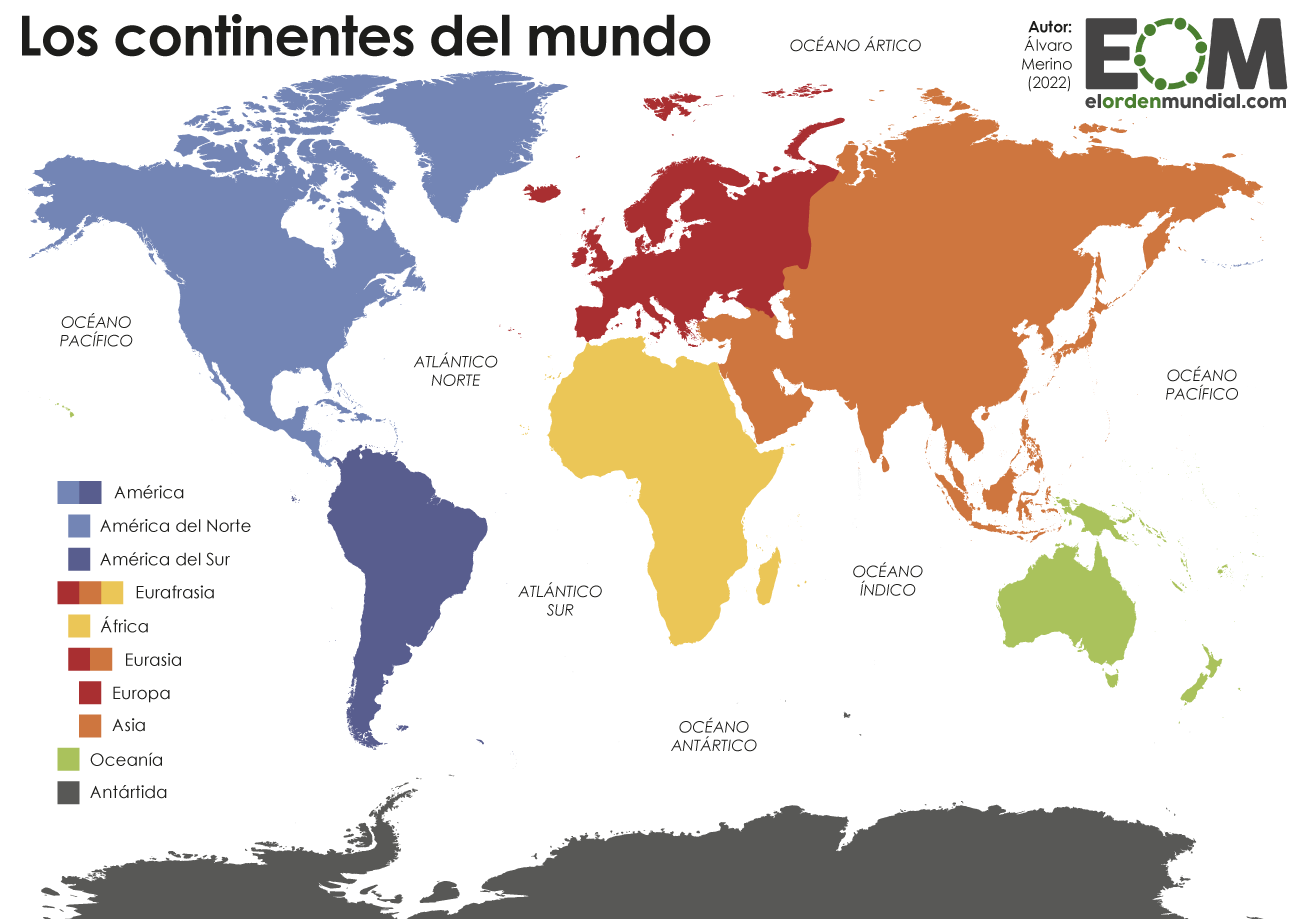

In any case, in the mid-20th century, we have a world divided into multiple continents. Something like this, shown on this map.

The reality is that there is no consensus. The education systems of different countries establish different continental divisions, although almost all of them fall into two groups: those that consider there to be six continents in the world and those that consider there to be seven:

The seven-continent model is the one that prevails in the English-speaking countries and is the most widespread in the world. This includes countries such as the United States, India, Indonesia, China, the United Kingdom, Germany, Australia, and Canada.

The six-continent model (combining the Americas) is the one studied in most Romance-language countries, as well as Greece. This includes Spain, Italy, Portugal, and all of Latin America.

It seems like a simple discrepancy: the problem would only be in considering America as a single continent or two separate continents: North America and South America. But I have omitted a third model, the one studied in Russia and some Eastern European countries. It also considers six continents, but in this case it keeps the two Americas separated, and it joins Europe and Asia to form Eurasia.

The continents according to geologists

The idea of unifying Europe and Asia into Eurasia is certainly appealing. After all, we are usually taught that continents are large areas of land surrounded by water, so why is Europe considered a separate continent? We have already seen that the reasons are purely historical and cultural, so from a geographical perspective, it would be logical to consider Europe and Asia as a single continent: Eurasia.

But if we want to be pedantic, isn’t Eurasia also connected to Africa via the Isthmus of Suez?6 This would mean that there is only one large continent: Afro-Eurasia. Or Afroeurasia. Or Eurafrasia.

Using the same reasoning, we can settle the question of the Americas. North America and South America are connected by Panama7, leaving us with a map like this.

With this model in mind, let’s dig deeper into the idea that Australia is a continent. I am going to focus on Australia and not on the idea of Oceania, since the islands included in Oceania hardly fit into the concept of contiguous land. What boundary do we use to differentiate between Greenland, with 2.2 million square kilometres, which is an island, and Australia, with 7.6 million square kilometres, which is a continent? It is clear that, once again, this is an arbitrary boundary. But it is also true that somewhere we have to draw the line.

If we talk about Antarctica, we also encounter problems. It is twice the size of Australia, with more than 14 million square kilometres, at least when it is covered by its imposing ice cap. If we stripped Antarctica of its ice sheet, we would find that it actually hides an archipelago8. Its main island would be somewhere between the size of Greenland and Australia, so we would have to decide whether Greenland would remain the largest island on the planet or Australia the smallest continent. With this new land mass in Antarctica, we couldn’t have both.

With all this in consideration, what do geologists think? Well, geologists say that the concept of a continent is not scientific, so it is a meaningless conversation from a geological standpoint. For them, the way that makes sense to divide the Earth’s surface would be by tectonic plates.

Tectonic plates are each of the fragments into which the Earth’s lithosphere is divided and which float on the Earth’s mantle. The most widely accepted classification establishes a total of 15 major tectonic plates and more than forty minor ones. All of this can be simplified in a map like the one below.

At a glance, it is clear that this does not solve our problem with the continents, but rather complicates it even further. The African plate, the Antarctic plate and the South American plate are the only ones that correspond entirely to the continent above them. The Eurasian plate would lose the Arabian Peninsula and Hindustan, and the Australian plate would include multiple surrounding islands. The North American plate, for its part, would lose part of the south to the Caribbean plate and would correspond to a large chunk of eastern Eurasia.

So, what is the most correct number of continents?

We return to the original answer: there is no correct number. All we have seen so far are different conventions that establish a number of continents based on history, cultural context and a great deal of arbitrariness.

By popular demand, here’s a button for procrastinating, in case you have plenty of things to do, but you don’t feel like. Each time you click on it, it will take you to a different map from the more than 1,100 in the catalogue.

If you like what you read, don’t hesitate to subscribe to receive an email with each new article that is published.

Or simply the Great Sea, as it was known in Ancient Greece.

The word used in Greek was ἤπειρος, which meant exactly that, contiguous lands.

We do not have any original copies of the world described by Anaximander or Hecataeus’ drawings, but there are reproductions based on the writings of other Greek thinkers.

I already wrote about this in the newsletter a few months ago, in the Babylonian world map.

I also wrote about this in detail a few months ago: The discovery and conquest of Antarctica.

Here I am going to ignore the existence of the Suez Canal, as it is man-made.

I am also going to ignore the existence of the Panama Canal, for consistency’s sake.

All this without considering that if the Antarctic ice melted, sea levels would rise. The Earth’s surface would also rebound and rise hundreds of metres, as it would no longer be under the pressure of five kilometres of ice. The actual calculations would be much more complex.

Love maps - like this known world map from back when.

Thanks for the footnote about the ice. This is consistent with my contention that this planet is still in an ice age, because there is still enough ice to sink continents. And not only Antarctica would rise – Greenland too (and for all I know might connect itself to the rest of North America.