Europa Regina

The story of how the myth of the abduction of Europa and the geographical creation of the European continent gave rise to Europa Regina, one of the most iconic maps of the 16th century.

A few months ago, I talked about how the idea of Europe is regaining a strength that seemed almost lost in the 21st century. At that time, I discussed all the federalist utopias that envisioned a future for Europe, but today I will focus on its origins.

Or at least the cultural origins that, in some way, we still share across much of Europe.

The myth of Europa

Hesiod and Homer, in Ancient Greece, are the first references we have to the figure of Europa, although her story may have preceded them by several centuries. She was a Phoenician princess who, like many other women in Greek mythology, was abducted by Zeus.

On this occasion, the Greek god transformed himself into a white bull to infiltrate the herd of Europa's father. Zeus appeared as a magnificent animal, achieving his goal of attracting Europa's attention. She approached the bull and, after seeing that it was friendly, decided to climb onto its back, which Zeus took advantage of to carry her away from her home.

After crossing the sea, the bull arrived with Europa on the island of Crete, where Zeus revealed his identity. The god of thunder had not asked his victim, but captivated by her beauty, he wanted to make her feel at home, so he made her the first queen of the island. In addition, to show his gratitude, he also prepared four gifts: a necklace made by Hephaestus; Talos, a giant automaton; Laelaps, a dog that always caught its prey; and a javelin that always hit its target.

As is often the case with Greek myths1, this is one of many variations of the story. Others simply say that Zeus, upon arriving on the island, had three children with Europa, after which he arranged for her to marry the king of Crete. In this other version, the gifts were wedding gifts for Europa.

Historians and anthropologists have offered interpretations of this myth and where it may have originated. It appears that the story may have its origins in a similar legend featuring the Phoenician gods Attar, in the form of an Arabian oryx2, and Astarte. With that in mind, the most common interpretation of the myth is the union between East and West, a way of bringing peoples and traditions closer together in the blooming Mediterranean of antiquity.

The European continent

As you probably know or suspect, Europe has not always been called Europe. In fact, when the first permanent human settlements were established, the territories did not have names of their own. If we go back to Ancient Egypt or Babylon, two essential civilisations of which we have records, they had an awareness of other peoples beyond their borders. Whether for commercial or military reasons, it was essential to name all the human groups with which they might interact, but it was unnecessary to name the land on which those peoples lived.

It was not until Ancient Greece that geography took on importance and territories began to earn their own names, regardless of their inhabitants3. The earliest references to Europe that we have on record are limited to mainland Greece, but around 500 BC, Hecataeus of Miletus wrote Periodos Ges, where Europe begins to resemble what we know today.

Hecataeus' work was divided into two volumes, one dedicated to Europe and the other to Asia, which also included Libya4. Starting at the Strait of Gibraltar, the Greek author travelled along the entire coast of the Mediterranean and Black Seas, describing the places and people who inhabited them. Although only fragments of his original work have been preserved, we find one of the first references not only to Europe, but also to other regions such as India and Iberia.

The definition of Europe is somewhat controversial. Around the 1st century BC, only the Bosporus Strait was used to define Europe as everything to the west, but with the division of the Roman Empire, the term was also used to refer to the Western Empire. With the expansion of Islam, Europe was relegated to those territories that had not been touched by Muslims. We can say that it was not until the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the conquest of Granada in 1492 that the current identity of Europe began to consolidate.

Europa Regina

With a defined idea of the European continent, the well-known myth of Europa and advances in cartography in the 16th century, the wonderful idea of Europa Regina emerged.

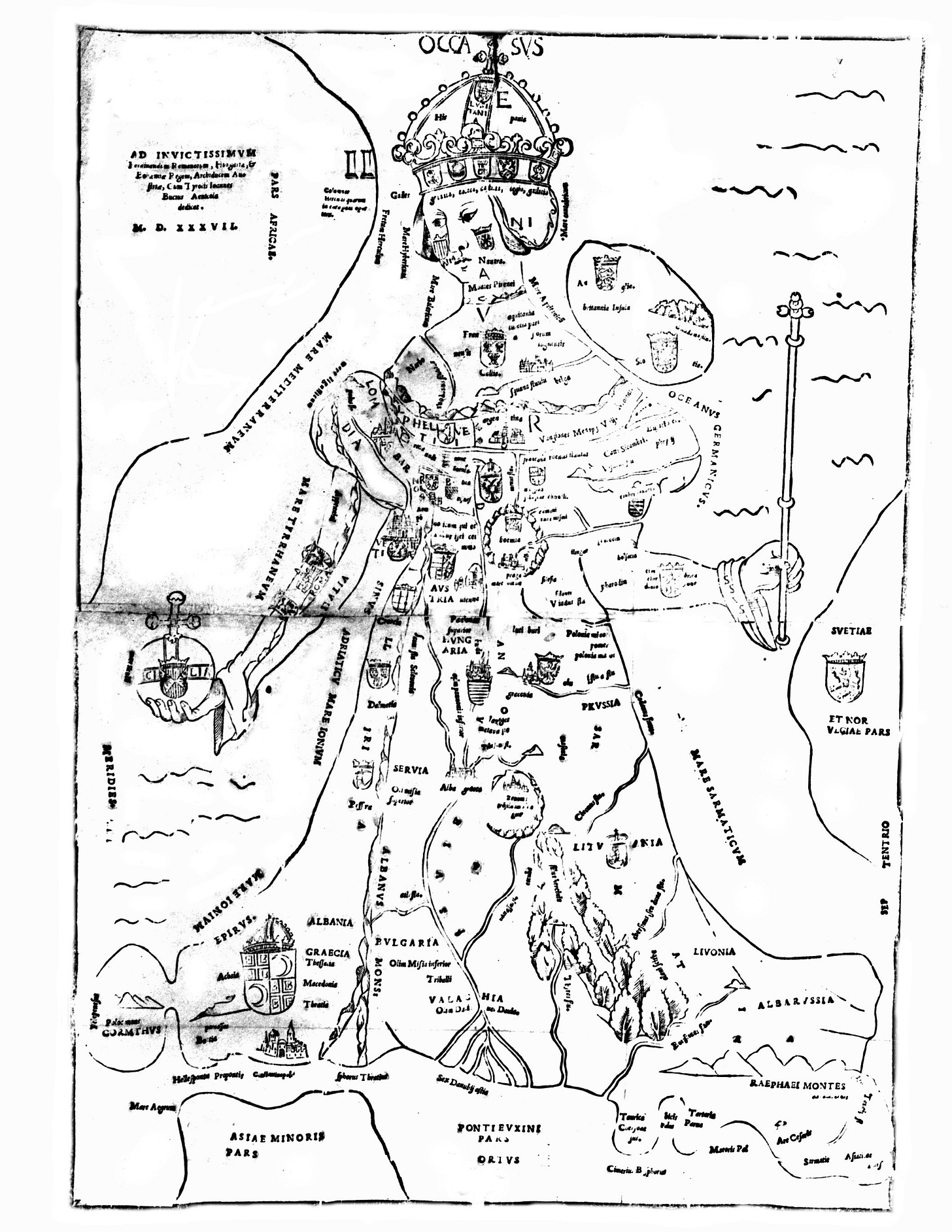

This is a scanned image of the first map depicting Europe in the form of a woman. It is a work by Johannes Putsch, of which only one copy remains in the Tyrolean State Museum. The map had no title, but we know that his contemporaries referred to it as ‘Europe in the form of a maiden’. Despite this, it is clear that the attributes with which Europe appears, crown, sceptre and orb, are more typical of royalty than of any regular maiden.

There is no record of Putsch's intention with this map, but we do know that the author had a close relationship with Ferdinand I of Habsburg. The map can be interpreted as a tribute to the House of Habsburg and its supremacy on the European continent. Whether this was Putsch's intention when he drew his map, the idea caught on with later cartographers, who renamed it to Europa Regina. Possibly, the most iconic of all the reinterpretations of this map is the one that appears in Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia5.

In this version, many of the details present in Putsch's map, such as coats of arms and cities, have disappeared. It is undeniable that Münster's copy gains a lot in artistic terms, but it does so at the expense of geographical accuracy, reducing the geographical features represented and the number of regions into which Europe is divided. All this seeks to enhance the myth of Europe, who appears surrounded by water, while at the same time showing a continent united under the central power of the Habsburgs and, indirectly, the Catholic Church.

And, in general, with any popular myth that has not been standardised by an institution.

It is not a white bull, but it is a white animal with horns.

Although, in practice, many territories were named after those who inhabited them at a given time.

Libya was how Africa was known in Ancient Greece.

If you are interested in learning more about the maps of Europa Regina and their many versions throughout the second half of the 16th century, I recommend having a look at this excellent article published by Peter Meurer in 2008.