Daylight saving time

How it began as a complaint about not being able to make the most of the daylight, and then it was established due to the need to save energy in times of scarcity

This article is part of a trilogy on time. You can read all the parts here:

A few weeks ago I thought that, taking advantage of the month of March, it would be a good idea to elaborate on daylight saving time and tell a little of the fascinating history behind it. I'm not usually one to plan texts well in advance, but I do like to structure them before I start writing so that they make sense. Within 30 minutes, I realised that it was impossible to tell the story I wanted to without writing a text that was too long for this format. That's why a couple of weeks ago I started a trilogy on time, talking about the days of 24 hours, which I continued last week with time zones, and I finish today with this article on daylight saving time.

Time zones were excellent for adapting to an increasingly interconnected world, and they facilitated the coordination of activities between distant locations. Initially, they were only useful for the railway network and telegraphs, but they soon also came to be used for planning radio and television broadcasts.

Despite its beneficial side, it inevitably had an impact on society as a whole. Human beings had adapted their lives to sunlight and, in a matter of decades, the day was no longer dictated by the sun but was subject to the arbitrary 24-hour system which, in some way, forced another way of understanding time.

The origin of daylight saving time

Industrialisation changed the world. Among other reasons, it introduced the need to impose working hours on workers. In reality, this was not one of the first effects, as it took decades of proletarian struggle for factories not to be in operation from dawn to dusk, but with set working hours, with some spare time throughout the week1.

These schedules began to establish interesting routines for factory workers. Farmers still started their day at sunrise, whatever the time, but the factory workers were stuck to the pre-established working day. For part of the year this meant getting up with the sun, but in the months leading up to the summer solstice they could get up many hours after sunrise. Their routine, like that of the farmer, revolved around work; however, working hours were no longer governed by daylight hours.

![r/MapPorn - Sunset/Sunrise times in Europe Summer/Winter [OC] r/MapPorn - Sunset/Sunrise times in Europe Summer/Winter [OC]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!sQ1J!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa011f3ad-2f2f-44f8-91fd-00aee294f042_2382x1804.png)

The first to formally expose this problem was the entomologist George Hudson. He was born in England in 1867, but settled permanently in New Zealand in 1881, where he spent his spare time to collecting insects, after his day work at the post office in Wellington. This caused him great frustration in summer, when he would see a handful of daylight hours before going to work being wasted, hours that he could not enjoy after work.

This led him to write an article in 1895 in which he proposed a change during the equinoxes to set the clocks forward two hours in all regions at latitudes above 30 degrees2. In his proposal, he tried to explain how this time change for six months of the year could improve the lives of many citizens. They would have plenty of time to enjoy gardening, cycling, or any other outdoor activity. As it is often the case with many pioneers, his proposal went nowhere, and he was mainly mocked when he presented it to the Royal Society of New Zealand.

It makes sense that the first proposal should have come from New Zealand, especially if we bear in mind that it was the first country to adopt time zones and leave local time behind. Soon, more voices were raised around the world, as was the case of William Willet. This English builder was passionate about golf, and deeply bitter about watching his colleagues sleep for hours after sunrise, while he saw summer nights arrive before his desire to play golf was fully satisfied.

Willett formalised his idea in an article published in 19093. The proposal was different to Hudson's and, in my opinion, much more interesting. It consisted of progressively advancing the clocks during the four Sundays in April, 20 minutes each Sunday, so that everyone could enjoy 80 more minutes of light in the afternoons during the months of May, June, July, and August. During the month of September, the clocks would be put back another 20 minutes every Sunday, thus returning to the usual time.

Among all the considerations in his article, the economic aspect appeared for the first time. The proposal included a total of 210 hours of sunshine that people normally spent in bed, for 210 hours of sunshine that society could take advantage of. His calculations, which he did not detail, amounted to a total saving of two and a half million pounds among the entire population of Great Britain and Ireland. That money would be saved on electricity, gas, and even in the use of candles by society as a whole4.

Energy saving and the imposition of daylight saving time

Hudson and Willet's proposals were not implemented, but they did manage to spark a debate that was taken to the representative chambers of many countries. Port Arthur and Fort William, in the Canadian province of Ontario, were the first localities to implement daylight saving time changes, in 1908. Other small towns followed their lead in the coming years, but they did not manage to influence national policy in this respect.

The First World War was the real trigger for the implementation of daylight saving time in several countries for the first time. As Willet had rightly pointed out, there was an energy cost associated with spending a few hours of the day in bed, as it meant having to use candles, gas, and coal to keep the light on after dark. In fact, saving coal was the justification used by the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire to establish summer time for the first time on 30th April 1916.

Despite being on the enemy side, many other countries followed in the footsteps of the Central Powers. In 1916, almost the whole of Europe joined in with this energy saving, including France, Italy, Poland, and the Ottoman Empire. A year later, Russia, Spain, and Romania also joined in. The war ended in 1918, and with it the pressure on the possible energy cost of not implementing daylight saving time. Of course, in a world without any significant supranational entity, each country decided to continue or not on its own.

In the United States, summer time had been planned for 1918, but the end of the war limited its implementation, so it was left up to each state in the union. As could only be expected, this resulted in an unnecessarily complex system, with some states ignoring it completely, others embracing it and the most creative with a mixed system. This was the case in New York, which in an attempt to please the primary sector and industry, chose to put the clocks forward in New York City, but keep them the same in rural areas of the state.

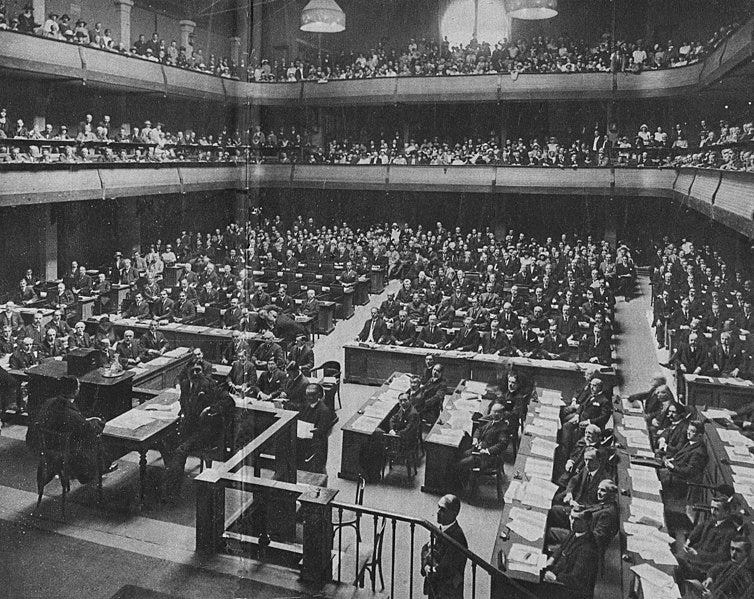

Europe transformed its diversity into a diversity of policies on changing the clocks. More than ten countries decided to abolish it at the end of the war, although a majority kept it for a few more years. Those that continued to change the time every spring and autumn also did not always do so on the same days, which began to cause multiple problems of international coordination. For this reason, the meeting of the League of Nations on 29 August 1923 had this item on the agenda5.

After adopting time zones, this new idea of summer time changes could once again jeopardise international coordination and cooperation6. Seventeen countries presented their different positions, all of them varied, but it was concluded that it would be beneficial for all to establish some good practices. There was no mandate on what each country should do, but the European countries did agree to give neighbouring countries notice of their plans. This would allow coordinating the time changes on an agreed day.

The interwar period continued with many countries ceasing to implement daylight saving time, although the Second World War brought summer time back to most of the world. The idea of the energy savings it could provide had got stuck in society, and no country wanted to waste resources in the midst of the most important conflict in history.

The present and future of daylight saving time

After the end of the Second World War, many countries once again opted to eliminate summer time, but one pattern remained at the international level. Each country continued to implement summer time when it was determined internally that there was a need to establish energy savings, whether due to war or scarcity. In Argentina, it was maintained until 1969, the United States standardised the diversity of state policies in 1966 and Europe consistently embraced summer time since the 1973 Oil Crisis.

Recently, more and more countries have been abandoning the daylight saving time change, resulting in the following map for 2025.

New Zealand, part of Chile and part of Australia, the only three regions in the Southern Hemisphere that still observe daylight saving time, are shown in orange. In the Northern Hemisphere, in blue, it is shown where it is applied, including all of Europe, Egypt, Israel, Cuba, Haiti and much of Canada and the United States. Perhaps the most interesting thing about the map is how it shows in light grey all the countries that have ever applied summer time throughout history, and in dark grey all the countries where this practice has never been established. Can't you see a pattern? That's right, it has never been applied in most countries with low latitudes, as the seasonal variation in sunlight is minimal.

The debate is still ongoing in practically all the countries that still observe summer time. With technological changes, the energy expenditure associated with light is constantly decreasing, making potential energy savings increasingly difficult to justify7. Even more difficult if we put on the other side of the balance the impact on the health of changing the time twice a year.

The latest studies provide inconclusive data on the energy effects of changing to summer time. A meta-analysis carried out by Stanford University suggests that the saving could be only 0.34%, rather than the 5% that had been suggested decades ago. Some studies even go in the different direction, such as the one carried out in the state of Indiana, USA, in 2007. In there, it was found out that daylight saving time not only failed to reduce the energy bill, but increased it by 1%.

The European Union had planned to abolish the time change in 2021, but a pandemic threw all plans out the window. The European Commission has asked the various members for plans, but so far, there is no consensus in place. Spain, the country that affects me directly, stated that at least until 2026 the clocks will continue to be adjusted every last weekend in March and October.

Lately, more and more countries have chosen to stop changing the clocks. Some countries, such as Iran and Brazil, have stopped applying daylight saving time, while others, such as Paraguay and Morocco, have decided to keep summer time permanently8. The case of Morocco is particular, as they apply daylight saving time across the year, except the month of Ramadan, when the daylight saving time is suspended.

In the coming years, more and more countries will leave behind the time changes and, in a way, I would bet that it will be a thing of the past in a couple of decades. Who knows, maybe we will look back and consider these practices to be a strange 20th-century ritual that took us a few decades of the 21st century to get rid of.

And that's it for this particular trilogy on time. I hope you've enjoyed it and that it will give you something to talk about.

The 8-hour workday first appeared in Australia and New Zealand for some skilled workers in the mid-19th century, although it did not become standard for all workers and in the rest of the world until the beginning of the 20th century.

The seasonal impact on daylight hours throughout the year is greater the further away you are from the Equator. To give an example, Dublin has almost 17 hours of daylight at the summer solstice and barely 7 hours at the winter solstice. The counterpoint may be Caracas, with 12 and a half hours of daylight at the summer solstice and 11 and a half hours at the winter solstice.

Here is the article by Willet, highly recommended reading.

On the subject of candles, I have to mention that Benjamin Franklin already elaborated on possible savings on candles in an article published in Paris at the end of the 18th century. That article did not mention a change in the time zone (they didn’t even exist at the time), but sought to make readers aware of the importance of getting up early. That is why I have not included it in this article.

In this PDF, you can find the summary of the session. It is interesting to see the points of view of the representatives of the different countries. By the way, this session also discussed the problem of calendars, as many countries still used the Julian calendar instead of the Gregorian calendar.

Although in reality, the First World War and the Second World War were obviously a much more problematic issue regarding international collaboration.

We must not forget that the time change is also supposed to reduce energy consumption for heating and air conditioning.

Which can also be considered a change of time zone.

Great post. Here's a map from the old days before time zones. What a mess https://forgottenfiles.substack.com/p/time-before-time-zones-1865