A world in perspective

The history of the first bird’s-eye view maps of cities, Saul Steinberg’s map and its importance in satirical cartography.

Behind every map, there is a story that wants to be told with a specific intention. To achieve this, you need to choose the region of the world you would like to represent, what information you intend to provide, and what visual tools will present that data. These are some of the parameters that determine whether we end up with maps as diverse as one of the bus routes in Baghdad, one of the Amazon River basin or one of terraformed Mars1.

Perhaps the parameter that usually creates the most interest when talking about maps is cartographic projections. As I have already mentioned here, cartographic projections are the transformations that allow us to represent the Earth on a plane. They have a geometric-mathematical basis that facilitates an approximation to the plane in which we know in advance what its strengths and weaknesses will be, but without perfection being possible2.

However, the perspective used in maps does not always follow a mathematical definition. There are maps that walk the line between artistic interpretation and cartography, which in itself is another parameter for telling a story with a very specific intention.

Today I will explore early bird’s-eye view maps, and introduce you to an interesting type of map that Saul Steinberg popularised in the 1970s.

Cities from a bird's-eye view

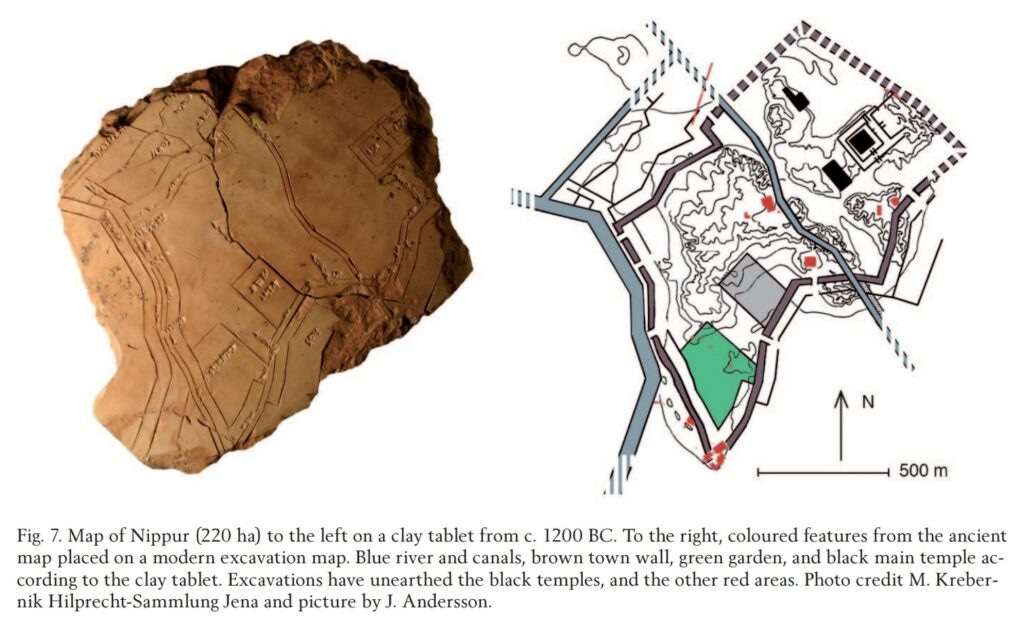

The representation of cities on a map dates back several millennia. It is possible that representations of the surrounding territory existed even before the first cities were created, so we can assume that even some of the earliest settlements had some kind of rudimentary map. The materials used were probably perishable, so the oldest city map we know of is that of Nippur, in Babylon, dating from around 1200 BC.

Those sketches were far from sophisticated, but they served a clear purpose. As cities grew in importance, they also found their way into other areas of cultural production in different civilisations. In 1997, beneath the Baths of Trajan in Rome, archaeologists found a set of fascinating frescoes, which are the oldest evidence of a city represented in art with a bird’s-eye view3. There is no consensus on which city it may be, and it is even questioned whether it is a particular city at all, as it could simply be an artistic representation.

Be that as it may, this fresco highlights the growing importance of cities as part of culture.

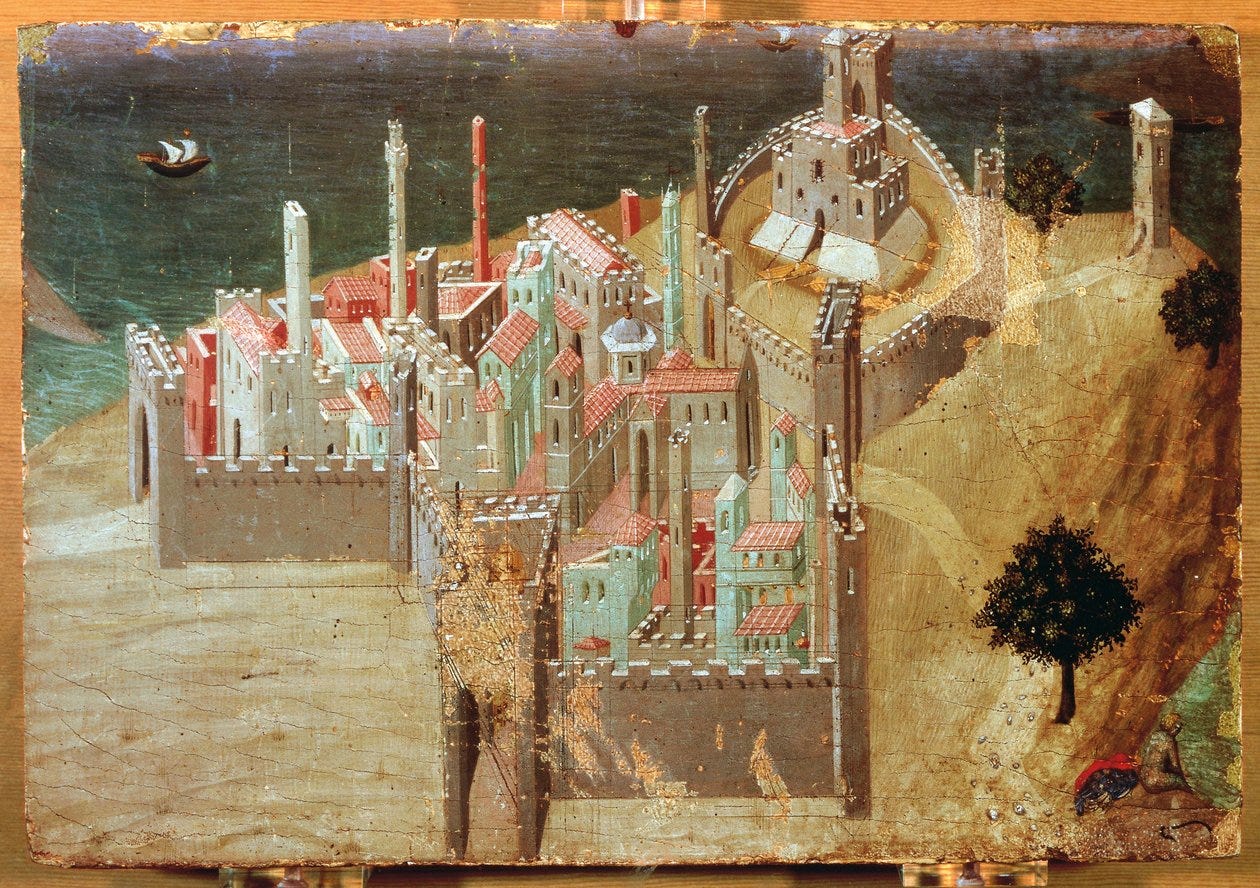

These representations became more popular throughout the Middle Ages, especially as a way of illustrating manuscripts and giving them character. In a way, they helped to provide context to the narratives, which were commonly linked to the religious sphere. The life of a saint was much better understood if his surrounding territory had a walled city, as this brought his figure closer to what any citizen of the time could experience.

In the mid-14th century, these representations began to gain importance, becoming a significant part of some paintings. Perhaps the piece that best represents this trend is Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s City by the Sea. Although not an iconic work in art history, it marks a turning point from which specific cities would begin to be represented with this iconic bird’s-eye view.

This brings us to the end of the 15th century, when cartography and art finally came together in a new trend that would allow cities to be shown faithfully. At the same time, it provided the artistic touch that a bird’s-eye view offers. It is difficult to pinpoint the moment when the complete transition from mere works of art to maps with high cartographic value took place. However, some maps were undoubtedly key, such as that of Florence by Francesco Rosselli or that of Venice by Jacopo de’ Barbari. There are many examples from this period, but I like these two because Rosselli still had a clear artistic interest, while de’ Barbari was meticulous enough to be considered a true map.

The world from New York

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, the bird’s-eye view continued to be used quite regularly. After all, it was still a good way to hang a representation of a city on the wall, with much more artistic content than most maps of the time.

At the beginning of the 20th century, based on this type of perspective, John Tinney McCutcheon had a genuine idea. He was possibly the most important cartoonist in Chicago at the time, and was known for his constant search for new ways to represent the world of his time with a satirical touch. McCutcheon had already been interested in maps previously4, but none of them had been as disruptive as the one he published in 1922 for the Chicago Tribune: The New Yorker’s Idea of the Map of the United States.

McCutcheon took the bird’s-eye view that had been used repeatedly to represent cities and, instead of limiting himself to the mountains, seas, or skies that usually mark the horizon, he took the opportunity to represent much of the world. In the centre of the map are two New Yorkers in the garden of their house, which is none other than the New York Stock Exchange building. To the left is the Capitol in Washington, and to the right is a school, possibly referring to Boston and its surroundings, where the main universities in the United States were located at the time.

Everything behind them, which the New Yorkers in the cartoon refer to as their backyard, is a completely simplified map of the United States. There are fields of corn, cotton, tobacco and wheat, which refer to some of the belts that define regions of the United States, such as the Corn Belt, the Wheat Belt and the Cotton Belt. There is also a garage, possibly referring to Detroit; oil fields, referring to Texas; and the Great Lakes, labelled as a fishing pond. In the background, marking the boundary, you can see the Rocky Mountains, the Pacific Ocean and a sun that could even refer to the Empire of the Rising Sun, Japan, located on the other side of the ocean.

The map was clearly critical of the attitude of New Yorkers, who continually believed themselves to be the centre of the country, minimizing the importance of other regions. It was a perfectly structured satire, and possibly influenced another map that appeared in 1976 on the cover of the New Yorker: View of the World from 9th Avenue.

This map by Saul Steinberg exaggerated the image of New York even further, simplifying everything that exists further west. Taking Ninth Avenue, one of the westernmost north-south streets in Manhattan, as a reference point, he drew everything that can be seen from there towards the west. The buildings on Ninth Avenue are shown in great detail, as are the pedestrians and vehicles travelling along the streets. As the illustration approaches the Hudson River, it loses detail, as if it were a real perspective.

Once across the Hudson River, everything changes. The coast is labelled Jersey, the state on the other side of the river. Beyond that, everything becomes a tangle of states and cities that simplify the territorial complexity of the United States to the point of absurdity. There is also a reference to Mexico on the left and another to Canada on the right. As in McCutcheon’s map, the Pacific is also important, and on the other side of this great ocean you can see three pieces of land representing China, Japan, and Russia.

Other cities with a global perspective

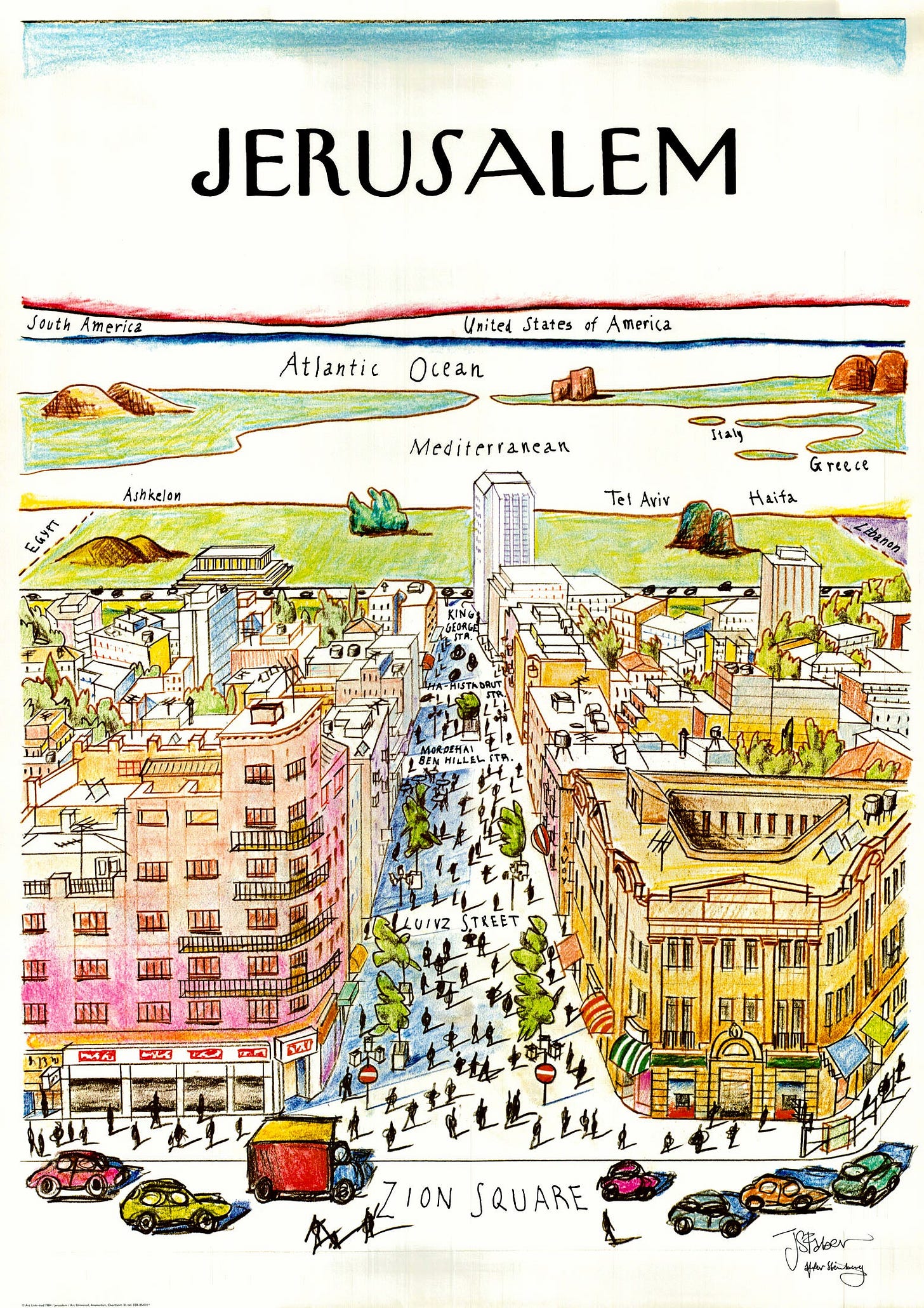

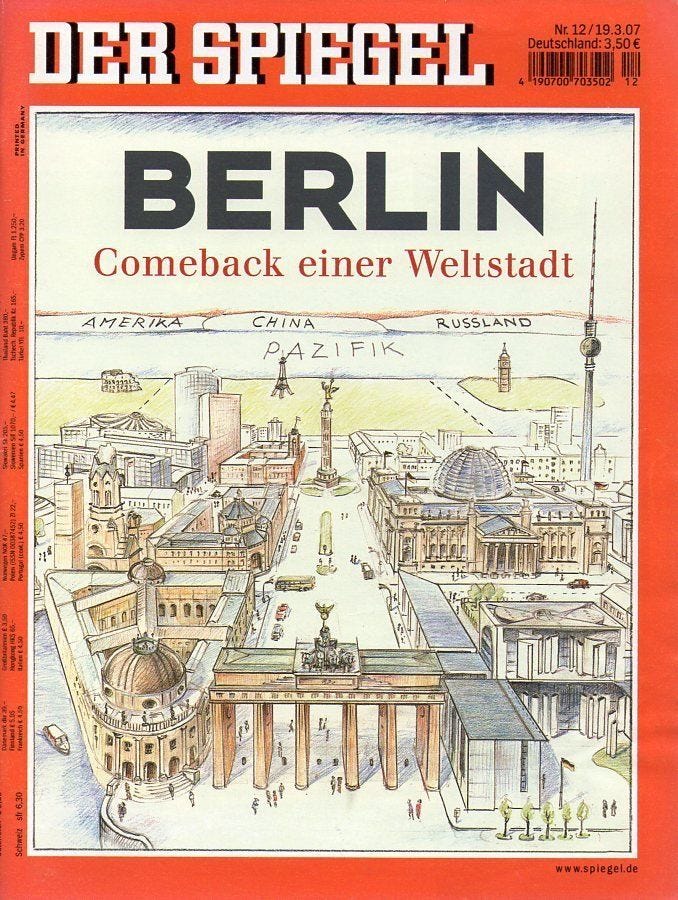

Although Steinberg was not the true inventor of this type of satire, he was the one who made it popular. Steinberg drew 85 covers for the New Yorker throughout his career as a cartoonist, but this one remains the most recognised of them all. Its popularity is such that the idea has since been replicated many times around the world.

And no wonder, as these types of maps have tremendous potential to criticise the excessive centrality with which some cities in the world live, despite their actual weight in today’s world.

Here are some of my favourite examples, although there are many more.

I have chosen three quite unfamiliar maps from the map catalogue. It is currently in Spanish, but you can also navigate it leveraging Google Translate in this link.

The sphere is a non-developable body on the plane. If you are interested in the mathematical basis behind it, this is a nice article to dig into (PDF).

Here is the article about the discovery, in case you are keen to learn more.

McCutcheon is also the author of this other fabulous satirical map from 1908, which I will also have to talk about here at some point.