Kadesh: history is written by the victors

A journey through one of the best-documented battles of antiquity. With special attention to historiography and how this battle is one of the best examples of survival bias.

As much as some may believe that history is what is written, the truth is that there are many prisms through which it can be viewed and understood in different ways. At first glance, it is easy to fall into the fallacy of taking the facts and versions selected by one side and accepting them as true. In a way, when history was still an immature science, this was often done. If the classics of Greece and Rome had one version of history, what could people living more than a thousand years later contribute about events that happened so long ago?

Fortunately, history has continued to be formalised over the last few centuries, and we have understood the importance of understanding the sources, as well as the possible biases they may have. The Battle of Kadesh is one of the best examples we have of how not understanding this can lead us to interpret history in a biased way. Not only is it one of the best-documented battles of antiquity, but we have also located sources later that have helped us to better understand what happened and why the history was written in a particular way.

Ramesses II, the only version for 3,000 years

Ramesses II began participating in the military campaigns of his father, Seti I, from a very young age. When he came to power in 1279 BC, Ramesses II had already fought in Libya, Nubia and even reached Palestine and Canaan in the Levant1.

Taking advantage of this experience, during the first five years of his reign he carried out multiple campaigns in the region to consolidate the commercial influence of the New Kingdom of Egypt in Ugarit, the port city of the Amorites.

Ramesses II's mission lasted five years and culminated in the Battle of Kadesh, on the current border between Syria and Lebanon, where the Egyptian pharaoh won a decisive victory. The success was such that, on his return to Egypt, the ruler dedicated several temples with different low reliefs depicting the history of the battle. These showed how the Egyptian army had won a crushing victory and how Ramesses II had become the hero of the battle, defeating hundreds of enemies with his own hands.

To accompany the low reliefs, the pharaoh also replicated the Poem of Pentaur on walls and papyri throughout Egypt, recounting the events in verse. In addition, the Bulletin was also incorporated, providing further details about the Battle of Kadesh to complete the version that Ramesses II established in his land.

The iconography created by Ramesses II after the Battle of Kadesh was only the beginning. During his 66-year reign, the second longest in Ancient Egypt, Ramesses II also built many monumental structures, such as the Ramesseum, his own necropolis, and Pi-Ramesses, the new Egyptian capital in the Nile Delta. In all the temples and buildings he erected, Ramesses II included statues depicting himself as the ideal powerful pharaoh, hero, and leader of the Egyptian people.

The idea of a prosperous Egypt and a heroic pharaoh transcended his death. He became one of the many pharaohs who built the mythical character of Sesostris, included by Herodotus in his Histories, and obtained a privileged position in Manetho's list of Egyptian kings. These Greek and Hellenistic sources were of great importance in how Romans2, Hebrews and Arabs perceived the idea of Ancient Egypt as a powerful and prosperous empire. This idea eventually crystallised in Western European culture.

In the 18th century, Romanticism began to attract some Europeans to visit Egypt. Claude Sicard, on his way through the Nile Valley, became one of the first to reach Luxor and confirm that it was the ancient capital of Thebes. He travelled throughout the region between 1708 and 1712, and everything he discovered was recorded on his 1717 map.

Greek sources spoke of this fascinating land, but the new tourists of the 18th century were able to confirm that it was not a myth, but a great reality. The fascination grew, but it was not until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and its interpretation by Jean-François Champollion that the hieroglyphics could finally be translated and the primary sources verified.

And yes, it was confirmed that Ramesses II was the image of the four colossi flanking the entrance to the great temple of Abu Simbel. He also was the person represented into the 17-metre-high statue in the temple of Luxor, and he had 250 other statues from Ancient Egypt dedicated to him. This validation allowed the myth of powerful Egypt to continue to spread. The texts also confirmed that Ramesses II was the one who had won the Battle of Kadesh and regained influence in the Levant.

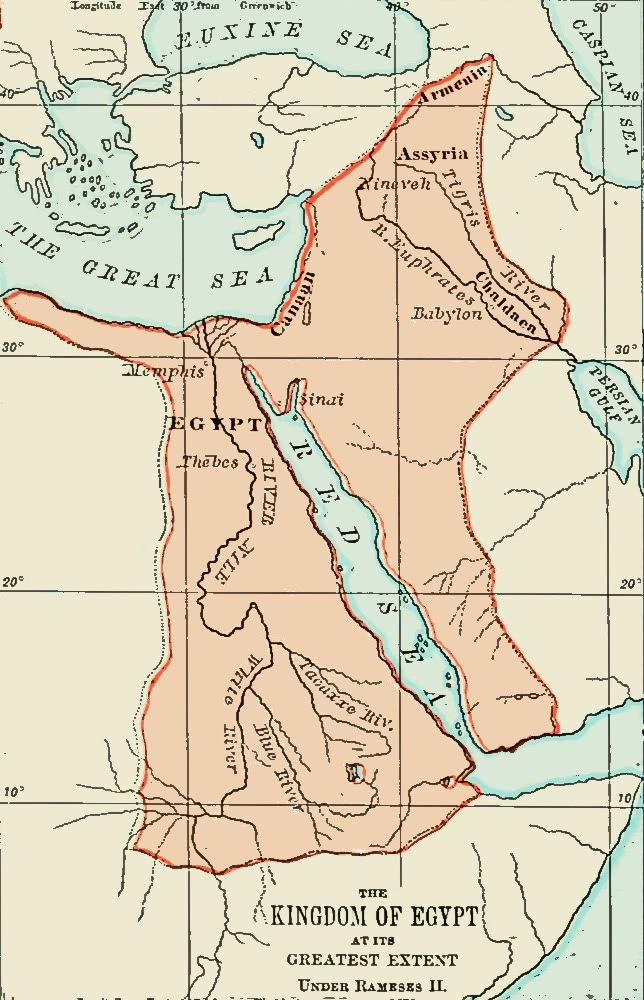

This map exaggerates the idea of the territory that Ramesses II came to occupy during his reign in a historical atlas from the late 19th century. Not only does it assign Canaan, in the Mediterranean Levant, but it also places regions as far away as Armenia, Babylon, and even much of the Arabian Peninsula under Egyptian control.

The Hittite Empire, the others

The fascination with the Middle East in the 18th and 19th centuries was not limited to Egypt. It also led many European explorers and archaeologists to rediscover the past hidden in the Fertile Crescent, the Promised Land, and even throughout the Anatolian peninsula. It was there, near Boğazkale, that Charles Texier came across some immense ruins in 1834. That city turned out to be Hattusa, the capital of the Hittite Empire.

Until the mid-19th century, the Hittites were barely mentioned in contemporary sources. They were generally considered an insignificant people from southern Anatolia, as references in biblical sources show. As excavations progressed, multiple artefacts and more references appeared, showing that the Hittite Empire was more than previously believed.

The improvements in the interpretation of old sources and, above all, the great achievement of deciphering cuneiform writing changed the history completely. At the end of the 19th century, it was clear that the Hittite Empire was on an equal footing with the other great powers in the region. The sources found throughout Anatolia stressed that its power extended far beyond the capital, and their content referred to the Egyptians, Assyrians, and Babylonians. This relationship of commercial and military respect was reciprocal, as the texts found and deciphered in Babylon, Assyria, and even Egypt also contained respectful references to the Hittites.

In 1906, during excavations in Anatolia, the German Hugo Winkel found some clay tablets that recounted the events of the Battle of Kadesh in Hittite, but for the first time from the Hittite perspective. Muwatalli II, king of the Hittites in 1274 BC, led the army that faced Ramesses II. This army not only included Hittite troops, but was also accompanied by several smaller peoples from the region, who sought to limit the influence of the New Kingdom of Egypt in the broader area.

A joint analysis of Hittite and Egyptian sources suggests that, in reality, the battle was not a victory for Ramesses II, as he claimed, but ended in a draw. This draw did not benefit either side, as both the Egyptians and the Hittites suffered heavy casualties, so we can consider that both lost out, and we can even go so far as to say that Egypt came off worse. When Ramesses II returned, Egypt lost almost all of its influence in the Mediterranean Levant for good3.

The survival bias

Today, the Battle of Kadesh is one of the best documented battles of antiquity. We have numerous sources that recount the battle from the Egyptian and Hittite sides, as well as the oldest peace treaty known to us. But, as we have seen, this was not always the case. For more than 3,000 years, all sources were directly or indirectly Egyptian, while the rest of the sources could not be used to understand what had happened there.

With new discoveries since the 19th century, it has been possible to reconstruct a history that is somewhat closer to reality. We now know that, even though Ramesses II was considered the most important pharaoh of Egypt several hundred years ago, the reality is that his reign was a brief period of prosperity in the midst of the decline of the New Kingdom of Egypt. In fact, almost all of his prosperity was reflected in the monumentality of his buildings, but he did not participate in any substantial changes in the prosperity and functioning of the empire.

Today, historiography seeks mechanisms to overcome this survival bias. It is not only a question of analysing existing sources, but also of being able to understand the extent to which these sources are reliable and what their possible motivations were. More importantly, we need to know how to evaluate which possible sources we do not have. All those writings and buildings that, actively or passively, were destroyed and have not survived to the present day.

If we return to the example of Kadesh, we have multiple sources from the Hittites and Egyptians, but in both cases the sources only represent the ruling elites. With this, we can reconstruct history, but we are aware that we do not know the opinions of other social strata of the Hittites and Egyptians, nor those of some nearby peoples who may have been involved. What's more, there may be peoples so small and irrelevant that we may not even know of their existence.

It is impossible to claim that we will ever write history in a way that is faithful to the reality of its time, but we can establish limits within the unknown, making clear at all times the uncertainties and possible interpretations.

The history is right perhaps, but let us not forget, it was written by the victors.

Alexis Guignard, 1842

I have brought you this quote from Alexis Guignard because it is the first I have found that refers to this idea, but it is something that has been repeated many times throughout history. The idea is appealing, but I think it is critical to qualify it.

The victors, or rather those who remain in power, are the ones who write the chronicles and decide which sources are preserved and which ones are discarded or destroyed. Historians and archaeologists are responsible for analysing all available sources, understanding who was behind those sources and what interests they might have wanted to defend, and assessing which sources are not available. With all this information, an interpretation of the facts is constructed, which will have to be continuously revised as new sources are found or new perspectives emerge.

The Levant refers to the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. I clarify this because I did not know that some people confused it with the Spanish Levante, on the opposite side of the Mediterranean Sea.

Both Hellenistic Egypt and the Roman Empire needed this list of kings to legitimise their power in the region. It is common in history, and in the world of propaganda, to establish a continuous line linking you to the leaders who brought a particular region to its greatest glory.

In 1903, the first reconstruction of the Battle of Kadesh was made, which only included Egyptian sources. From 1912 onwards, many more reconstructions were made, including and interpreting the sources that were appearing. Here is a good example from 1996, which shows groupings, flanks, and even the number of chariots used by each of the combatants. It even includes the initial ambush by the Hittites, which almost led to an immediate victory.